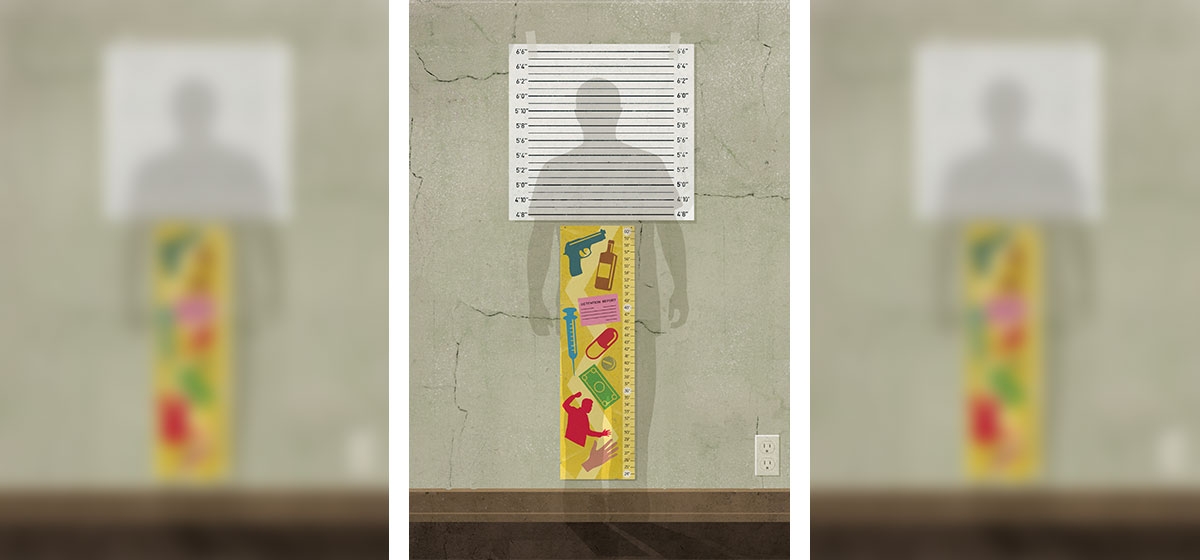

Path to Delinquency

Aaron Thomas was 14 when a Pittsburgh police drug task force raided the Garfield home where he lived with his parents, whose lives were ruled by an addiction to cocaine and heroin. That led to his first encounter with the juvenile justice system. But the time he would spend in and out of jail, youth detention centers and diversion programs was foretold years earlier.

More than once in elementary school, he arrived home to find his family evicted and his belongings strewn outside. More than once he and his older brother walked the streets all day, bundled against the cold with blankets, instead of staying in their house without lighting or heat. School was marked by suspensions and absenteeism and void of meaningful academic achievement. Before he was 10, he regularly witnessed his parents getting high at home, often with other addicts.

At 12, Thomas started selling drugs. His first sale was cocaine he took from a stash belonging to his older brother, who had started dealing when he was 11. By high school, they were known as the “coke brothers.”

In urban slang, “coming off the porch” means leaving the innocence of childhood to start a life hustling in the street. “We shouldn’t have come off the porch that young,” said Thomas, now 37 and a father of three. “But we had situations where we had to be on those streets to survive and maintain.”

Thomas is a survivor. His life turned in his early 20s and he’s stayed straight since, building his first full-time job as a peer educator into a career with the Allegheny County Department of Human Services, where he recruits and trains young adults with similar backgrounds to keep adolescents and teens from following the same path.

Juvenile court cases involving delinquency charges have decreased by more than 40 percent in the U.S. since 1997, when such cases reached their historic peak. But Thomas and his colleagues needn’t worry about a shortage of young clients.

More than 3,300 young men and women were referred to juvenile probation in Allegheny County last year. More than 75 percent of the referrals were for nonviolent offenses, such as drugs, theft and failing to pay court fines. Nearly three in four of those referred were young men, and 69 percent of those young men were black, underscoring the stark racial disparity that prevails in juvenile justice throughout America. Overall, 2,672 young Allegheny County men and women were placed in secure detention or in alternative-to-detention facilities, such as residential treatment shelters.

‘No one ever listens to us’

Regardless of the severity of their offense, or the dire circumstances they may confront at home, these children are often viewed as trouble at school and in their communities. And they know it, a new study by The Pittsburgh Foundation suggests.

“I was just labeled… a bad kid,” said a young man of 16, one of 53 Allegheny County youths involved in the study who have experienced the juvenile justice system or whose behavior and circumstances have brought them to the brink of entering it.

The young people shared their experiences and perspectives in a series of Foundation-sponsored focus groups that explored who they are, the circumstances they deal with and their reflections of the juvenile justice system. This nontraditional philanthropic approach is intended to shape the programs The Pittsburgh Foundation funds by using the insights of the people it’s trying to help.

It’s part of the Foundation’s 100 Percent Pittsburgh initiative to address regional disparities that linger despite Pittsburgh’s broadly admired recovery and “most livable” accolades.

“Something we heard constantly was, ‘No one ever listens to us,’” said Jeanne Pearlman, the Foundation’s senior vice president for program and policy. “Even nonprofits don’t listen to kids. It’s not that we don’t care for them, love them. We don’t value their wisdom and their complicated lives. It’s the context in which they live that often puts them in a place where they get involved in juvenile justice. These young people have that lived experience. They are the subject-matter experts on how to avoid entering the system.”

A wide range of experiences detrimental to children’s development is found among those who find their way into the juvenile justice system, studies find. Poverty and the hardships it imposes top the list. Family dysfunction, mental health issues, drug use, school suspension, living in distressed neighborhoods, abuse, witnessing violence and other trauma-inducing incidents are also common.

The local young men and women in the study’s focus groups suggest they are no exception. “Food not coming in, so you try to be a man,” confessed a young man of 21. “You see everybody else outside making money, so you try to do it too. You start skipping school; that’s when you get caught.”

An 18-year-old man said, “I didn’t grow up in an environment that was financially stable. I grew up in the projects. That caused me to do certain things that put me in wrong situations.”

Thomas understands. He and his brother skipped school when their addicted mother’s monthly public assistance check arrived to coax her to buy groceries. “If one of us didn’t do that, we weren’t eating for the month. That check was gone. Drugs—gone that day.”

For Amber Knight, conflict with her mother and the stigma of poverty growing up in the city’s Hill District neighborhood influenced her journey to juvenile probation and confinement in the state’s North Central Secure Treatment Unit in Danville, Montour County. As a teen, she’d already started a street resume that would include selling drugs and prostitution. It belied her ranking as a top student in school, when she attended.

“In the surroundings I was in, there were people—neighborhood drug dealers and people who did other things—who had a lot more than I did. It was the easiest way to make money,” said Knight, now 34 and a county Youth Support Partners mentor to young women whose lives resemble her experiences. “It was an older crowd. For the most part, I hung with adults. My mother was poor, and I had a lack of respect for anyone without money because I had latched onto that lifestyle. After a while, my mom couldn’t handle me. She couldn’t get me to school; couldn’t get me to cooperate with curfews. She wasn’t able to tell me anything.”

Troubles at home and school

Children who experience poverty and hardships that lead to involvement in human services ranging from child welfare to mental health treatment are far more likely to struggle in school, according to Allegheny County Department of Human Services data. A one-year snapshot of the Pittsburgh Public Schools, for example, found 53 percent of district students were involved in some type of human service. Only 47 percent of them had grade point averages of at least 2.5 compared with 72 percent of their classmates who never received services.

Skipping or being suspended from school only lessens the chances of such children having academic success and graduating. Suspension and chronic absenteeism is common among youth in the juvenile justice system. Ninety seven percent of those who took part in The Pittsburgh Foundation focus groups had been suspended at least once. In some cases, it can take as little as a dress code violation for a student to draw a school suspension.

Suspension practices are increasingly being reconsidered in districts across the country amid concern they contribute to the “school-to-prison pipeline”—the notion that schools unwittingly create an environment for criminalization when they implement certain practices to curb violence, including zero-tolerance policies, and the presence of police, metal detectors and probation officers in schools.

The rate of school suspensions is falling. In Allegheny County, the rate dropped from nearly 19 suspensions per 100 students in the 2011–12 school year to 14 per 100 students in 2014–15, state Department of Education data show. But wide racial disparities in who is suspended linger. More than 68.5 percent of students suspended countywide were African American in 2014–15, only slightly less than three years earlier when blacks accounted for 70 percent of suspensions.

At 39 suspensions per 100 students, few districts in the county match the rate at Woodland Hills. Yet, few districts have done better reducing its suspension rate, which peaked at 70 per 100 students in 2011–12, when it ranked as one of Pennsylvania’s 10 highest. Only 7 percent of the suspensions that school year were for acts of violence or having a weapon.

The consequences of such numbers were not lost on Superintendent Alan Johnson when he arrived in 2012. “We were suspending an extraordinary number of kids. Most of them were black and most of them were black males.

“When children miss school, they fall behind. Some are already coming in with an educational disadvantage for whatever reason. They miss school. They come back. They are far behind. They are lost in the class. They start to misbehave. That leads to separation from class. Initially, it’s a visit to the office. Then, it’s detention. Then suspension. When they’re suspended, they’re out even longer. When they come back, they’re even farther behind. The cycle builds rapidly.”

Woodland Hills rewrote its code of conduct and other policies to add flexibility to the disciplinary process. Fighting and carrying a weapon still earn students an out-of-school suspension. But language and dress code violations no longer automatically result in banishment. Teachers are told to set aside the books during the first few days of the year and get to know their students. They are trained to acknowledge the preconceived notions and bias that may color their judgment of students. And their in-service days now include instruction on how to recognize, understand and respond to trauma.

“It’s not only about realizing kids have challenges,” Johnson said. “It’s also understanding that most of us wouldn’t be able to get out of bed if we had to live the lives of some of our kids. We couldn’t deal with it. But they are. They’re getting up, getting dressed and coming to school.”

Research suggests that it’s a culmination of circumstances or experiences that lead children to juvenile offending, probation and detention. “It’s not one magical thing—that if the school hadn’t suspended them their lives would’ve turned out OK,” said Edward Mulvey, professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. “Think about piling rocks on a kid’s back and asking him to sprint 100 yards. The more rocks you pile on, the more difficult it’s going to be.”

“Think about piling rocks on a kid’s back and asking him to sprint 100 yards. The more rocks you pile on, the more difficult it’s going to be.” —Edward Mulvey, professor of psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh

Breaking the cycle

Once in, it can be difficult for children to extricate themselves from the juvenile justice system, say the local young men and women who’ve experienced it.

“It is so easy to get into the juvenile system and so hard to get out,” a young woman of 17 told researchers. Another young woman, 19, told the focus group: “What you’re charged with can be little. You get on probation and then things just keep adding up.”

Knight is familiar with the spiral. Her first taste of juvenile justice was being placed in a group home. When she ran away, she was put on probation. “When I was on probation I was so angry I would get more time for fighting. Ultimately, my three-to-six months ended up being three years.”

For her, a short stint in the county jail and the offer of a job with the county mentoring young women turned her toward the life she leads today as a homeowner and mother of four. “I had never had anyone give me an opportunity to be a professional. I didn’t want to go back to the street life after being in the county jail. That was the worst experience in my life. So, I started training and saw that I was really good at it and there was no going back.”

For Thomas, it was his quiet admiration of the men who staffed the residential placement program he was sent to that turned his head. “They were good-looking guys, dressed very well. They wore nice cologne, had nice cars, beautiful wives and nice houses. They were college-educated guys. They were what I aspired to be. I didn’t see many options for me at the time. But that was my first realization of what I wanted to do with my life.”

Such personal accounts, Pearlman said, have already informed The Pittsburgh Foundation’s approach. For example, their need for trusted adults to confide in has led to exploring ways to increase such contacts. Young women of color lament that juvenile justice programs designed to help young men leave little for them to relate to; that has led to exploring school- and community-based interventions tailored to their issues. The focus groups also inspired seeking ways to reform school curriculum to strengthen the self-worth of African American students. “One young African American woman said they have three weeks of black history in February,” Pearlman said. “They talk about slavery for three weeks as though her entire history is grounded in slavery. She was 16 years old. It was painful to hear.”

The study also makes clear that despite the trials of their childhood, the young people have not lost hope for better days and different lives. The ambitions they express are varied: To be a good mother, to be rich, to be a kindergarten teacher, a botanist, a pediatrician, a guard at the county Shuman Juvenile Detention Center, do drywall for a living, serve in the Marine Corps, play football, own their own business. And then there’s is the young man of 16 who simply wants “to live.”