Baseball’s Best Book

When Ty Cobb died in 1961, Lawrence Ritter thought that “someone should do something, and do it quickly, to record for the future, the remembrances of a sport that has played such a significant role in American life.” He decided that he would take a tape recorder and, traveling around the country, talk to as many old-timers as he “could find and ask them what it was like.”

The result of Ritter’s travels and conversations was the publication, in 1966, and enlarged in 1984, of The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It. When it first appeared in print, legendary Brooklyn Dodgers broadcaster Red Barber called it “the single best baseball book of all time.” Long-time New Yorker book editor Roger Angell praised The Glory of Their Times as “almost perfect…a vivid, gentle, humorous narrative, accompanied by marvelous photographs.”

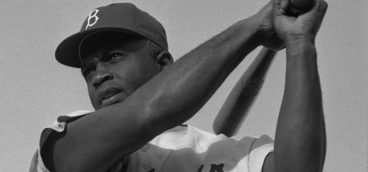

Among the many old-timers interviewed by Lawrence Ritter for The Glory of Their Times were former Pirates Tommy Leach and Hall-of-Famer Paul Waner. For the enlarged edition, Ritter added an interview with baseball’s first great Jewish star, Hank Greenberg, who, in 1947, played his last season in Pittsburgh, the same season that Jackie Robinson integrated baseball.

Tommy Leach spent his 19-year career playing third base alongside “the greatest shortstop ever,” the hulking, bow-legged Honus Wagner, who, according to the 5’6” Leach, “didn’t look like a short-stop.” But, playing on bad fields, Wagner “just ate the balls up with his big hands, just like a steam shovel, and when he threw the ball to first base, you’d see pebbles and dirt and everything else flying over there.”

Leach remembered playing in both the 1903 World Series, the first in modern baseball history, and the 1909 World Series, the Pirates first World Series victory. Leach thought the 1909 World Series against Ty Cobb and the Detroit Tigers was “mighty rough,” with “a lot of bad blood” between the teams, but nothing like the 1903 World Series against Boston, “probably the wildest ever played.”

Police swinging billy clubs and players wielding bats had to drive Boston fans from the playing field during the series, but the real threat, according to Leach was “that damn Tessie song.” Boston’s most fanatic supporters, called the Royal Rooters, instead of singing “Tessie you make me feel so badly/why don’t you turn around,” belted out, “Honus, why do you hit so badly/Take a back seat and sit down.”

In 1926, when Paul Waner at 5’8” began his major league career in 1926, the year after the Pirates came back from a 3-1 deficit against the Washington Senators to win their second World Series, he urged the Pirates to sign his younger brother, Lloyd. When Lloyd joined the Pirates in 1927, they played in the Pirates outfield together for 14 years on their way to becoming the first and, to this date, only brothers elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In 1927, the Pirates won the National League pennant but were swept in the World Series by Babe Ruth’s Yankees, regarded by many as the greatest team in baseball history. Paul Waner remembered all the great ballplayers on that 1927 Pirates team, but the player who stood out was Pie Traynor: “I think the greatest third baseman who ever lived…. A terrific hitter and fielder. Gosh, how he could dive for those line drives down the third base line and knock the ball down and throw the man out at first. It was remarkable.”

Waner also had a chance to watch Honus Wagner play shortstop, even though it was only in batting practice. Hired by the Pirates as a coach to help out during the Great Depression, Wagner would, once in a while, take his position at shortstop, and when he did “a hush would come over the whole ball park, and every player on both teams would just stand there, just like a bunch of little kids, and watch every move he made.”

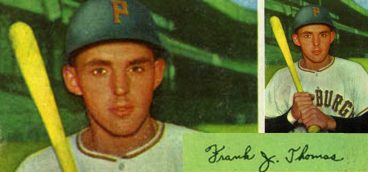

Slugger Hank Greenberg was baseball’s first great Jewish star and the first Jewish ballplayer to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. In 1946, his 12th season with the Detroit Tigers, Greenberg had an excellent season, leading the American League in home runs and RBIs, but the Tigers, not willing to pay Greenberg’s $75,000 salary, placed him on waivers.

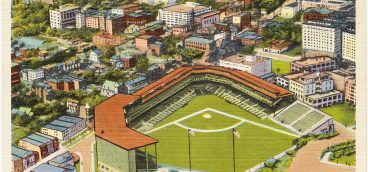

Even though the Pirates claimed him from waivers, Greenberg was so angry that he decided to “quit baseball.” But when Pirates owner John Galbreath met Greenberg’s every demand, including a salary of $100,000 and shortening the distance to the left field fence at Forbes Field from 365 to 340 feet, to match the distance to the left field fence at Detroit, Greenberg agreed to play one more year.

Greenberg had suffered anti-Semitic taunting through his career, but, he claimed if “you want to talk about real bigotry, that was what Jackie Robinson had to contend with in 1947,” including from Greenberg’s Pirate teammates: “we were in last place… and here’s some of our guys having a good time yelling insults at Jackie.”

Greenberg, who refused to play on Yom Kippur, “resented being singled out as a Jewish ball player.” When he was playing, he wanted to be “known as a great player,” but over the years, when he learned how important he was to Jewish kids growing up, he said, “I find myself wanting to be remembered not only as a great ballplayer, but even more as a great Jewish ballplayer.”