What Do I Know? Chris DeCardy

I was born in Urbana, Illinois, and grew up in Champaign, its “sister city,” about three hours south of Chicago. I spent my entire childhood there as the only child of a single mother. My folks were divorced when I was very young and, although my dad was in my life, my primary childhood influence was my mom.

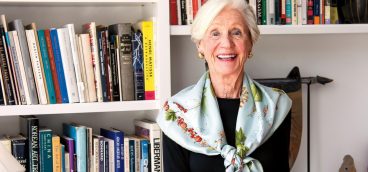

My mom is an artist who spent decades as a public-school art teacher. She also was a somewhat reluctant community activist. I was lucky to have an artist for a mom because, to be an artist, you must be constantly curious about the world, and about expression and connection. She nurtured that in me throughout my childhood.

My ancestors are from Western Europe and emigrated here in the late 1800s, through Ellis Island, ending up in Chicago, Indiana and Michigan. My mom’s family was from Chicago primarily, as was my dad’s. My mom’s father worked for the phone company, and my great-grandfather was a lineman during the period when the world was transitioning from the telegraph to the telephone.

- The Heinz Endowments, President (2023-present)

- DeCardy Consulting, Principal (2020-2023)

- ClimateWorks Foundation, Acting CEO (2021-2022)

- The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, Vice President and Director of Programs (2002-2020)

- Environmental Media Services, Executive Director (1995-2002)

- Harvard Kennedy School, MPP, Environment and Natural Resources (1994)

- University of Wisconsin-Madison, BA, Journalism (1987

As a society, the transition we’re engaged in right now is the movement from an industrial to a post-industrial era, into the “information age,” from Alexander Graham Bell to the smartphone, and this movement is impacting communities in disruptive ways. People are experiencing a great deal of uncertainty from this transition, which has accelerated since the 1970s. What do human beings do when confronted with uncertainty? We close up. We feel afraid and go into a “fight-or-flight” mode. We start to look to people who are most like us, and look for someone or something to blame for our anxiety.

In the world today, there is a strong undercurrent of emotion that is embracing division, separation, and disconnection, and we are focused increasingly on what is happening in the moment and what is not working. Some people believe that the solution is to revert to an earlier time, when life seemed safer. It is important to understand that the ways of “simpler times” worked for some people but did not for others. And as we hurtle into the future, it is equally important to realize that the leaders of that future are already here, but many of their voices aren’t being heard.

From the time I was a kid, my mom made sure that I was connected to adults and mentors who had strong values that were aligned with hers. One of those was a junior high school history teacher who was an environmental advocate. He took me out for canoe trips on the Vermillion River, which flows into the Wabash and, in turn, flows into the Ohio. I loved being in nature and, as a result, a connection with the environment was tangible for me. I loved the peacefulness of the forest and the exploration of streams. And it was fun to just explore and get dirty. All of that resonated, and stuck with me from an early age.

For as long as I can remember, I was also drawn to team sports because I loved the competition and the camaraderie, the coming together of people with different skills to achieve a common goal. Through sports, I learned how people can motivate each other, and that became a passion of mine. Sports also introduced me to the divisions that exist between people: racial, economic, rural versus urban, and so on. I had grown up middle-class, so it’s not like I had to overcome prejudice. I was just another white kid living in a predominantly white community. But by getting to know my teammates, many of whom came from very different backgrounds and situations, I learned to see people as unique individuals. On occasion, our coach would take us out for ice cream after a game and then drop us off at our homes: one kid at a three-story brick mansion and, 10 minutes later, another at a small, somewhat rundown home. The differences in our living conditions were stark. I am thankful for those experiences, and for the close friendships I developed with my teammates.

Growing up, I was allowed to watch only 30 minutes of “junk TV” per week and I devoted that to the “Pink Panther” cartoon on Saturday mornings. The only other TV I was permitted to watch was the news. In the early ’70s, the two biggest things going on were the Vietnam War and Watergate. So, as a kid, I took in all of it, and remember thinking, “Wow, these people are doing important stuff.” There was Walter Cronkite, telling us about everything that was happening in Vietnam. And then there were Woodward and Bernstein, explaining Watergate. I realized that journalists are paid to be curious about the world and are tasked to find out what’s really going on. The best journalists have proven that you can actually shape what the future will look like. That thinking took me from high school in Illinois to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which had a really fine journalism school.

In college, I worked at The Daily Cardinal, the student newspaper, mostly on the city and campus desks. A team of reporters and an editor wrote the editorials, and I enjoyed sitting in on their discussions. They had huge arguments all the time, especially about Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy and how it was altering the world. When I was a junior, I said to myself, “I’m 19 years old and have never traveled beyond the U.S. border.” In fact, I had never flown in an airplane. Then I came upon a study-abroad opportunity that seemed interesting. I could go to London, take classes on Mondays and Fridays, and do an internship during the middle of the week. So, I got an internship with BBC Radio for six months, and then with a member of Parliament for another six. It was an extraordinary opportunity. And since the British Parliament had no budget for staff, I got to do all sorts of assignments even as a goofy American who had only a basic knowledge of what really was happening. It was terrific.

If my mom was very important to me, her mom was perhaps even more so. My grandmother was the type of person everybody deserves to have in their life: someone who loves you, no matter what. But she could be fierce, too. Her motto was, “Don’t just sit there; make yourself useful.” So, as I prepared to graduate from college, and having been inspired by my year in London, I decided to join the Peace Corps. I wanted to learn and understand other cultures — and to make myself useful.

In the Peace Corps, I was stationed in the Philippines and set out to learn about my assigned community. I wanted to understand where the people were coming from, who their leaders were, and what they’d already accomplished. I was assigned the role of “water and systems engineer,” given my experience working construction during college. I was charged with helping to cap a spring to redirect potable water to a local school, which seemed like an important assignment. But as it so happened, the Catholic Relief Services were already there, and weren’t staffed by Americans. They were all Filipinos, and their method for making a difference was simple: Talk with community members and ask, “What do you need right now?” and “What can we do to help make it happen?” It turned out that the community, at that moment, needed a truck to haul their produce down a bumpy road for five hours to get it to market and sell it. They were having a hard time paying exorbitant prices for intermediaries to do this for them. So, lesson learned: Instead of telling people what you think they need, ask them what they need. After all, they would know that better than you would.

I left the Peace Corps before my time was up, unsure about what would be next. I had felt frustrated in the Philippines because, having been a liberal arts student, I didn’t think I had any tangible skills to be valuable there. So, I trained to be an Emergency Medical Technician (EMT) and got my certification. Ultimately, however, I learned that being an EMT wasn’t for me, although I was glad to have had the experience. I saw what it takes to be able “to deliver” every single day and I deeply admire first responders. Then, for the ensuing six months, I got a job delivering flowers, figuring, “What could be better than that for making you feel good about the world?” — and I really needed that. Ultimately, however, I headed to Washington, D.C., what I then thought of as the “center of the universe.”

It was the late 1980s and the nation was coming out of a deep recession. Consequently, it was difficult to land a job as a journalist, and I soon learned that I couldn’t just start in D.C.; I had to go to small-town America and work my way up. But I really needed a job. Before long, I discovered the world of public affairs and worked for a progressive PR firm that focused on causes and issues I cared about. I realized that I could be part of a group of people who were helping to engage and educate, and working with the political system to achieve change.

I was on the staff of that public affairs firm for four years and got to work with, among other groups, the African National Congress, just before Nelson Mandela was released from prison. Our firm did all the logistics for Mandela’s first visit to the U.S., which included his famous speech at Yankee Stadium. I was running media relations and got really engaged. One day, I got a call, amid the pandemonium of the visit. I picked up the phone and it was the legendary TV journalist Tom Brokaw, who was upset because, in the visit’s itinerary, Mandela was scheduled to appear on a network other than NBC. I got a lot of heat for that. Nevertheless, I knew that I was in the right space — supporting people who were already striving for change.

Next, I decided to go to graduate school to study government — at the Kennedy School at Harvard — to focus on environmental and natural resources policy. It was the fit for which I’d been searching. I care deeply about the environment and the promise of using market-based mechanisms for environmental protection. By utilizing such mechanisms, I believed, the world might well get the maximum environmental benefit at the least possible cost. Such thinking led, ultimately, to the 1992 Clean Air Act, which was phenomenally important in changing the environment for the better.

After the Kennedy School, I went to work for a “think tank” and did that for a time. Then I started a nonprofit organization that raised money from foundations to drive policy in D.C. by building long-term, strategic communications campaigns around particular issues. For example, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which won the Nobel Peace Prize with Al Gore in 2007, was releasing its assessments, which were essentially the underpinning of the action we are taking globally regarding climate change. Throughout the 1990s, the IPCC would issue reports — with no communications plan to support them. My organization came in and supported the lead of the IPCC and the authors, so that they could connect with and inform editorial boards at media organizations across the nation and the world. That was the model, and it was a good one, so I did that for quite a while. Then one day, The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, which had been supporting us along the way, told me, “We want to hire a communications director but we want a person who can integrate strategic communications thinking with our program strategies.” I said, “If you want to do that, I’m in.” So, they offered me the job and I accepted. After a series of promotions, I became the vice president and director of programs, and ran them at the Packard Foundation for 18 years.

Philanthropy is the ultimate expression of optimism and hope. It is the stewardship of resources that were committed in the past to be used for public good in the future. In 2020, I left Packard and, on an interim basis, ran a climate change foundation. Then this opportunity at The Heinz Endowments came about. I was interested because the Heinz family’s history of philanthropy is one that believes deeply in place, and is invested in community. It has been here for generations and believes in finding solutions to difficult problems collaboratively. And it will continue to support leaders and organizations who believe in working together. All of us have an opportunity to craft a future in which everyone can earn a good living and support a family or community by becoming part of the future, culturally and socially. Through The Heinz Endowments, I’ve been given a great opportunity to make a difference in the world. And I’m humbled to play my part.

Personally, I’m most interested in sustainability. But what will it take, ultimately, to get this country to address climate change seriously? Surveys show that some people today don’t trust or believe in science. This is nothing new. Historically, there have been people who didn’t believe in evolution, or that the earth revolves around the sun. But why? Such beliefs are often rooted in moral or philosophical ideas. Given the high level of polarization that exists in this country right now, much of the political discourse is driven by “Who do I identify with, and what are the indicators of that identification?” I don’t mean to be flippant about this but, for me, that’s not particularly interesting. What interests me is, “What are the pathways to connectivity among people?” Once we have an answer to that, those who might identify with groups in those divides will have a way to encounter each other as individuals. When they do that, they’ll find common values and pathways to a future we all want.