When Jim Thorpe Almost Became a Pittsburgh Pirate

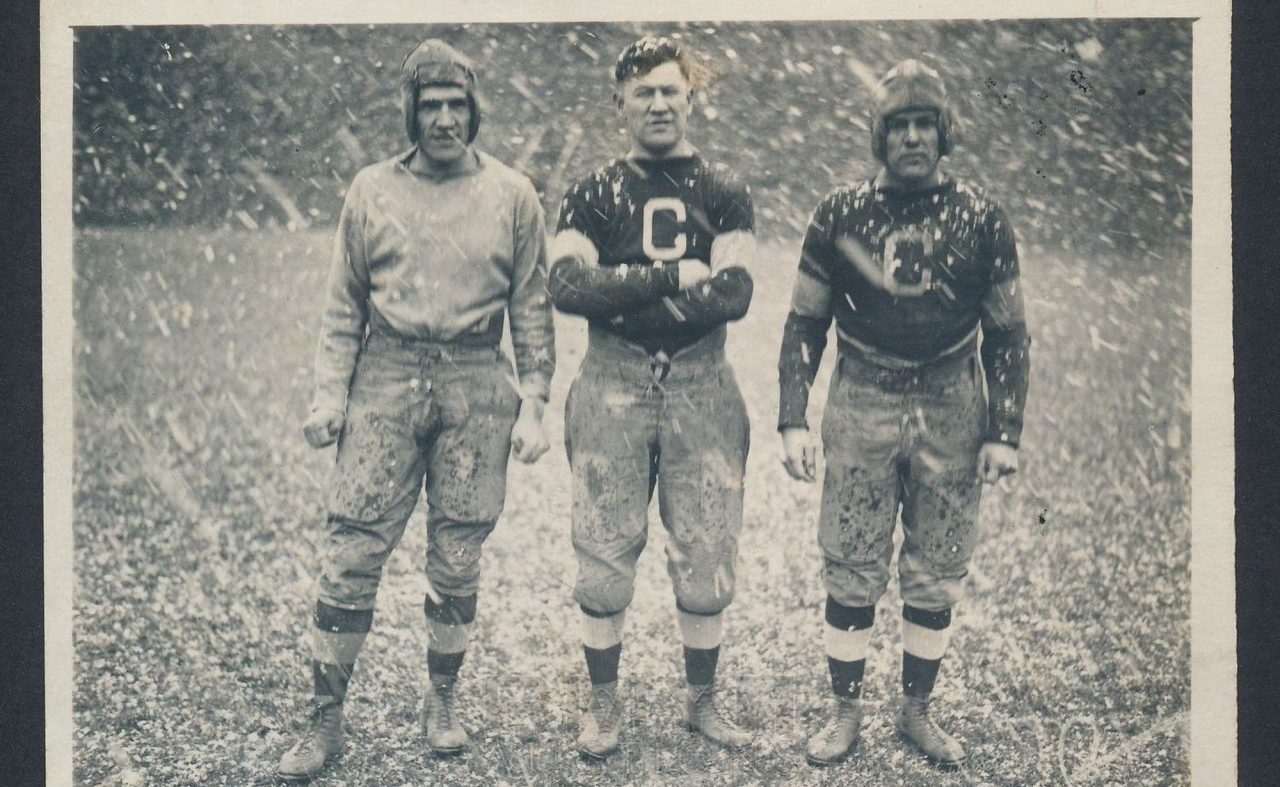

In the 1912 summer Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden, Jim Thorpe won the demanding five-event pentathlon and the grueling ten-event decathlon and was roundly declared the greatest athlete in the world. He added to his stature that fall by becoming a football All-American after leading Carlisle to a stunning upset over a powerful Army team that included Dwight Eisenhower.

The Carlisle that Jim Thorpe attended in the early 20th century, was founded in 1879 as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Its mission was to assimilate Native American children into white society, or, as stated in its motto, “Kill the Indian, Save the Child.” While the motto was an improvement over General Sheridan’s view that “the only good Indian is a dead Indian,” in reality, it was nothing more than a shift in government policy from the destruction of Native Americans to the eradication of Native American culture.

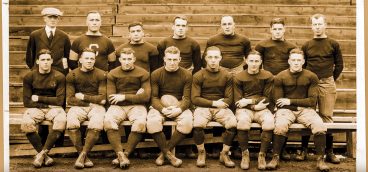

Carlisle became a football power in the first decade of the 20th century after it hired future Pitt coach Glenn “Pop” Warner from Cornell in 1899. Carlisle, as an educational institution, was basically a trade school, but it found out, under Warner, that it could make money by developing its football program and playing away games at the packed stadiums of the most prestigious college football teams in the East, including Ivy League teams, the military academies, and independents, including Pitt and Penn State.

While Carlisle’s football program was making money, there was little likelihood that its players, once they left Carlisle, could make money playing football. Professional football was in its infancy when Thorpe finished his college football career in 1912, and the NFL wouldn’t be founded for another decade. The only team sport where Thorpe could make money was professional baseball.

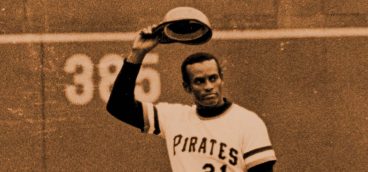

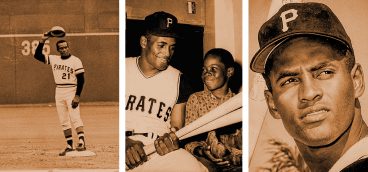

On August 11, just before the beginning of the 1912 college football season, a headline for the Pittsburgh Press blared “JIM THORPE to be a Pirate!” In the article, sports writer Ralph S. Davis wrote that Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss had made an offer to Thorpe, and that Thorpe had promised to sign with the Pirates once the college football season was over. Thorpe would be joining a Pirates team that, under the leadership of future Hall-of-Famer Fred Clarke, had remained a contender since it won the World Series in 1909. He would also become a teammate of Honus Wagner.

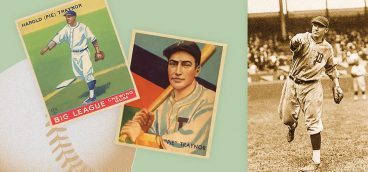

After the football season was over and before he signed a contract with the Pirates, the Worcester Telegram reported that Jim Thorpe was not an amateur athlete when he won his gold medals in the 1912 Olympics because he had played in the lower minor leagues in the summers of 1910 and 1911. College athletes commonly earned some money during the summer by playing professional baseball, but they played under assumed names. Thorpe made the mistake of playing under his own name.

Thorpe admitted that he had played minor league baseball before he competed in the Olympics, but he pleaded with the American Amateur Union not to take his amateur standing away from him and demand the return of his gold medals to the Swedish Olympic Committee. In a letter to the AAU, Thorpe claimed, to no avail, that he was “an Indian school boy and did not know all about such things. In fact, I did not know I was doing wrong because I was doing what I knew several other college men had done except that they did not use their own names.”

When the AAU rejected Thorpe’s appeal, forfeited his amateur standing, and demanded the return of his gold medals, the attention shifted to his future in professional baseball. He’d promised Barney Dreyfuss that he would sign with the Pirates, but that didn’t prevent other teams, including the New York Giants, from pursuing Thorpe. Under John McGraw, the Giants had won the National League pennant the last two years and saw a great drawing card in Thorpe as they pursued their third straight pennant. McGraw’s Giants made Thorpe his best offer.

It seemed unlikely that Dreyfuss would release Thorpe from his promise so he could sign with the Giants. Since the Pirates won the World Series in 1909, the Giants, along with the Cubs, had been their chief rivals, but Dreyfuss had a personal reason for hating McGraw and the Giants. Early in the 1905 season, Pirate player-manager Fred Clarke and McGraw got into a fistfight after McGraw taunted a Pirate pitcher. When Dreyfuss complained about McGraw’s behavior, McGraw turned on Dreyfuss.

In a game at the Polo Grounds, McGraw taunted Dreyfuss, greeting him with “Hey Barney,” and accusing him of everything from betting on games and reneging on his bets to controlling umpires through his friendship with National League Commissioner Harry Pulliam. Dreyfuss was so enraged that he filed a formal protest, complaining that, “steps should be taken to prevent visitors to the Polo Grounds from insults from the said John J. McGraw.” Dreyfuss lost his protest but he never forgot the humiliation he suffered at the hands of McGraw.

When Dreyfuss made little more than a token offer to Thorpe, McGraw stepped in and made a far more substantial offer, Dreyfuss, instead of matching McGraw’s offer, released Thorpe from his promise, even though Thorpe was willing to keep it and sign with the Pirates. On February 1, 1913, with a great deal of fanfare, Thorpe entered the offices of the New York Giants and signed a professional contract.

The reason Dreyfuss was so magnanimous may well have been his admiration of Thorpe’s willingness to keep his promise or his own unwillingness to match the Giants’ substantial offer, but that doesn’t take into account his hatred for McGraw. More likely, Dreyfuss had doubts about Thorpe’s ability on the field and his conduct off the field. Dreyfuss may well have recognized that Thorpe, while a great athlete, had played no baseball beyond the lower minor leagues and he had lost his gold medals after an international scandal. Dreyfuss , who took pride in running a clean ship may well have decided that Thorpe was not worth the risk on or off the field.

Thorpe’s decision to sign with the Giants proved to be a terrible and tragic mistake. While the Giants went on to win their third straight National League pennant, McGraw used the 26-year-old rookie in only 19 games. At season’s end Thorpe had batted only 35 times, had five hits, and batted only .143. In the World Series, Thorpe sat on the bench and didn’t appear in a single game, while Albert “Chief” Bender, who, like Thorpe, went to Carlyle, pitched Connie Mack’s Philadelphia A’s to a World Series victory.

For the 1914 and 1915 seasons, McGraw continued to use Thorpe sparingly. After spending the 1916 season in the minors, Thorpe returned to the big leagues in 1917, first, on loan, by McGraw, to the Cincinnati Reds, then back to the Giants. After playing part time with the Giants in 1918, Thorpe, complaining that he was tired of riding the bench, was shipped to the Boston Braves. Finally given a chance to play regularly, he hit .327, but was released by the Braves at the end of the season. The 32-year-old Thorpe never played in another major league game.

While Thorpe sat on the Giants’ bench year after year, he had plenty of time to brood over the loss of his medals and trophies. John “Chief” Meyers, who roomed with Thorpe during his years with the Giants, recalled that “he never got over what happened to him once the Olympics were over…. that broke his heart. It really did.” He remembered that, after a night of heavy drinking, Thorpe woke him up: “He was crying. Tears were streaming down his face.” He told Meyer, ‘“They’re mine, Chief. I won them fair and square.’”

After Jim Thorpe’s major league career was over, he continued to play minor league and semi-pro baseball in the hope of making a little money. His last effort came in 1933, 20 years after he signed his contract with the Giants. At the age of 46, he organized the semi-pro Harejo Indians, a team of Native Americans that barnstormed around the country and likely played the Pittsburgh Crawfords, a Negro league powerhouse with Josh Gibson, Oscar Charleston, and Coll Papa Bell. But the Harejo Indians were a financial flop, and Thorpe was finished with baseball.

On the evening of January 10, 1952, just a little more than a year before his death on March 28, 1953, friends of Jim Thorpe, recognizing that he was in dire financial straits, held a testimonial for him at Canton, Ohio. In the audience that night was Pittsburgh Pirates owner John Galbreath, while Pirates general manager Branch Rickey gave the keynote address.

Rickey, who just a few years earlier had integrated baseball, finished his speech by demanding the restoration of Thorpe’s medals, calling Thorpe, “unassuming, unmasking and uncrowned.” The audience rose to its feet to give Thorpe a standing ovation. Today we can only wonder how different Thorpe’s career in baseball and his life might have been if, instead of signing a contract with the demanding and unforgiving John McGraw, he’d signed with the Pirates, where he would have played with the support and encouragement of Fred Clarke and Honus Wagner.