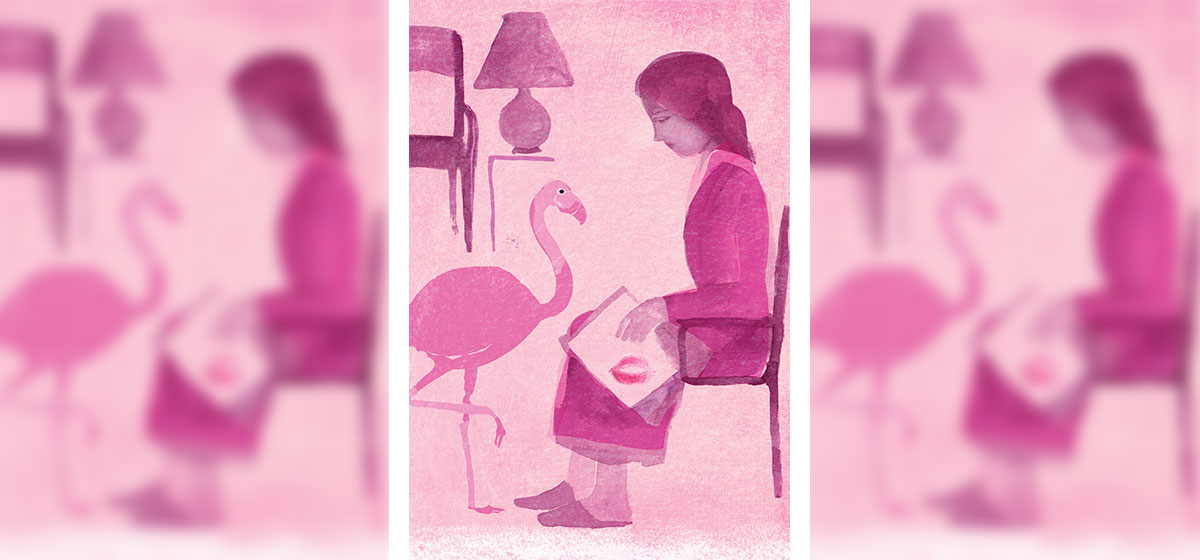

In the WomanCare Waiting Room, I Consider Flamingos

The pink robes at WomanCare smell like bleach.

I wonder how many times they’ve been washed and reused.

I wonder how many women have worn the robe I am wearing, how many of them were fine, how many were not fine, where they are now, if they have healed, if they are still here at all.

My mother wore a robe like this, many times.

My mother loved the color pink. Her favorite lipstick was from Sephora, a color called Pink Flamingo, the lipstick she wanted to wear in her casket because it would clash with her red suit and light her up like a Valentine, like a love letter about to be buried.

“It really lights up my face,” she’d say and purse her Flamingo’d lips into a kiss in the mirror.

My beautiful mother.

My sad lonely funny mother.

When she died, I found tubes of Pink Flamingo in her dresser drawer. I found tissues she’d used to blot.

“Make sure they use my lipstick,” my mother said when she was planning her own funeral. “Not some of that Frankenstein crap.”

All these tissues in my mother’s dresser drawer looked like shrouds, the imprint of my mother’s kiss on them.

I should have kept them, maybe. Yes.

* * *

In 1985, a 15-year-old boy was arrested for throwing rocks at African Great flamingos in the Pittsburgh Zoo. One of the rocks hit a flamingo and severed its legs.

The bird died.

“It was pretty,” the boy said. “I was just trying to make it fly.”

It’s strange the things that happen while you’re waiting. It’s strange the things fear makes you think about.

Pink breast-cancer ribbons look like flamingos.

Breast cancer ribbons pinned on breasts look like pink flags on graves.

* * *

In the waiting room at WomanCare, most of us avoid conversation and eye contact. Most of us flip through our phones.

A few of us, when our phones lose power, resort to the outdated magazines that fleck the lovely end tables, People, Good Housekeeping, Parenting.

Back in the waiting rooms of my childhood, Highlights Magazine had a feature, “Goofus and Gallant.” The comic featured Goofus, a jerk, and Gallant, a kind boy who believed in righteousness above all things.

The purpose of the comic was to teach children kindness. Good/bad. Right/wrong.

“Be kind babies,” Kurt Vonnegut said.

My phone is dead.

A soap opera is on one overhead TV, a talk show on the other.

The talk show is hosted by Dr. Oz, and this is an episode about the dangers of buying underwear in department stores.

People, it seems, are buying panties and bras and wearing them before washing them first.

Dr. Oz and his team of True Crime experts are investigating store-return policies. Far too many stores, Dr. Oz has discovered, restock used underwear and unsuspecting customers are buying them.

“Isn’t that illegal?” Dr. Oz, his famous eyebrows in a cartoon-villain arch, his voice a gasp, asks his research staffers, who say, “Absolutely, Dr. Oz.”

Dr. Oz’s staffers purchase 11 pairs of underwear from top chain stores and send them out to a lab for testing. All but one test positive for coliform bacteria. Half the samples also contain trace amounts of yeast. All but two samples are soiled with mold. No one has gotten sick from wearing store-bought, unwashed panties, but still.

The terror! The fear!

We live in an era of pre-emptive strikes.

I watch Dr. Oz hold up a fistful of poison panties in this pink-robed waiting room and imagine everything in the world is out to kill us all.

“I’ll save you!” Gallant from Highlights Magazine would say.

But no one can save anyone, I think.

Alex Trebek from “Jeopardy” had cancer.

* * *

In the waiting room, an older woman talks loudly to no one.

The woman wears shiny silver sandals. Our shoes, I start to realize, are one of the things that tell us apart.

The other thing is hair, its presence or absence.

This woman’s hair is stubbled in from chemo or radiation, maybe both.

Another woman in the room is completely bald.

When my father was dying of cancer, he worried a lot about his hair. He’d always had lovely hair, thick and wavy, and losing it hurt him. In his last few months, he wore that knit hat he’d kept from his World War II days. He pulled it low over his eyebrows. He fell asleep wearing it and my mother would slip it off. In the morning, my father would furiously reach around until he found his hat, the way people with bad eyesight grapple for their glasses, before they open their eyes.

My father felt shame, I think.

I feel shame.

I feel shame for worrying about my hair.

I feel shame for worrying about chemo and radiation, even though the doctor told me not to worry about any of that yet.

I feel shame for my own vanity, how much I fear chemo, the effects of that, the privilege of fearing the effects of that.

My hair is past my shoulders. I have been letting it grow and I keep it dyed blonde, even though the hair at my temples is almost pure white.

Here, in this place, my hair seems wrong, obnoxious.

More Goofus than Gallant.

I should have tied my hair back. The color feels fake and loud and shallow, yellow as a hazard sign, yellow as yield, yellow as the lemons bobbing in the water cooler, dead jaundiced fish.

* * *

Later, I will let my hair grow and keep growing. I will tell people I’m letting it grow before the doctors take it from me.

I don’t want my children to have to see me bald.

I will say, “With cancer, you never know how long you have.”

I will say this as a joke. I will laugh but it and my hair will make most people uncomfortable.

It will make me uncomfortable too.

But I will be out of touch with the part of myself that can say why.

* * *

Today, the woman who talks to herself is worried about parking, her meter expiring, how long she has been waiting.

I want to offer to go out and check her meter, to put some money in, but something about the waiting room, about the way none of us looks at one another, like we are afraid whatever we are waiting on is … contagious-—contagious, when we have already caught our own diseases—makes me keep quiet.

“I swear,” the woman is saying, “if I get a bullshit ticket on top of all of this, there will be hell to pay, let me tell you.”

The waiting room smells like lilies and roses.

Funeral flowers, I think.

Still, pretty.

There is a snack basket here, always a bad sign, a sign that things in this place are serious enough to require snacks. This snack basket is filled with Smart Popcorn and granola bars. Healthy, healthy.

I touch my hair despite myself. I pull strands to see if they hold. I examine the damage, split ends. I put a strand in my mouth the way I did as a nervous child.

“Stop that,” my mother would say.

I smooth the wet strand back down.

Still here.

Still here.