Allegheny County Meets Air-Quality Standard for First Time in Decades

After lagging most of the nation for decades, Allegheny County has managed to meet the minimum federal health standard for one of the most harmful of the major air pollutants, county health department data suggest.

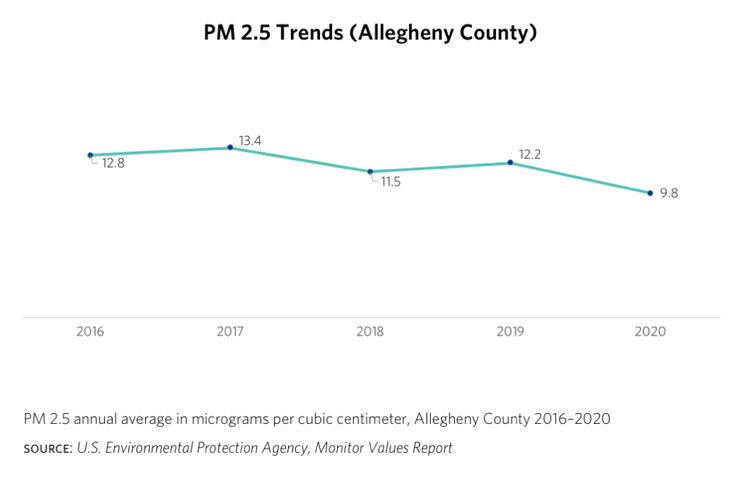

Levels of fine particulate pollution, known as PM2.5, averaged 11.1 micrograms per cubic meter of air over the last three years, dropping the county’s average below the federal standard of 12. It is the first time the county’s three-year average met the standard since it was set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency more than 20 years ago.

The county’s PM2.5 emissions have long been driven by high readings from a monitor in Liberty Borough downwind of the U.S. Steel Clairton coke plant in the Monongahela River valley. Last year, emissions fell to record lows in Liberty with help from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“It’s good news, because it shows improvement,” said James Kelly, Allegheny County Health Department deputy director of environmental health. “But there’s more work to be done.”

It’s unclear, for example, how a return to business as usual will impact vehicle and industrial emissions, which have thinned during the pandemic. County air officials are noticing more frequent weather-related episodes that trap pollution for days. And a recent EPA analysis of health risks shows momentum building for tightening the PM2.5 standard the county just met.

Stubborn problem

PM2.5 is one of the most dangerous air pollutants in the world. Made up of microscopic particles, it is difficult to see unless in high concentrations, when it appears as a haze.

When inhaled, the particles easily enter the lungs, bloodstream and other organs. A large body of scientific research links PM2.5 exposure to higher risks of heart and lung disease and premature death. The particles can linger in the air for long periods and travel hundreds of miles.

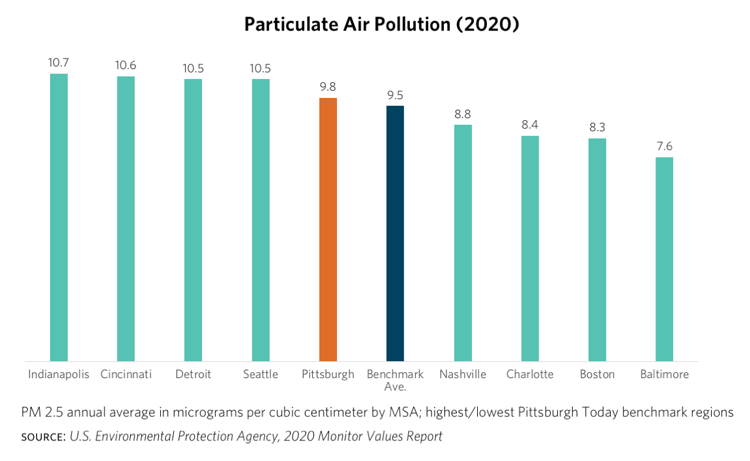

Allegheny County and southwestern Pennsylvania have struggled to tame air pollution more than most regions in the country. For two decades, concentrations of PM2.5 in county were among the worst in the nation, endangering public health and tarnishing the region’s reputation as one of the best places to live in America.

Sources of the pollutant include emissions from industry in the region’s river valleys and from upwind out-of-state power plants, especially those that burn coal. On-road vehicles are another source of emissions that can form PM2.5. And frequent pollution-trapping temperature inversions common to the region allow those emissions to linger for days.

Air pollution has been greatly reduced in the region in recent years, but most other U.S. metro areas have done better.

PM2.5 pollution recorded at the county’s Liberty monitor last year, for example, was less than half of what it was in 2000 — the result of years of technological advances, advocacy, tougher regulations, local enforcement actions, industry investment and economic factors.

That has helped the county’s three-year average of PM2.5 emissions meet the minimum federal health standard. If the EPA confirms the data later this year as expected, the county will be deemed in “attainment” of the standard for the first time — something 99.5 percent of the more than 3,000 U.S. counties have already achieved, including every other county in Pennsylvania.

Pandemic-related economic and travel disruptions helped lower those emissions last year. One battery at the Clairton coke works, for example, was put in “hot idle” and nearly all of the others went to extended coking time, which also reduces emissions, Kelly said.

But emissions from both local and out-of-state sources were already trending low enough that the county would’ve been in attainment of the PM2.5 even without the pandemic’s help, he said. “The backbone of our power grid was once overwhelmingly coal-fired [power plants]. Now, it’s overwhelming natural gas-fired. That’s a large reduction in emissions from what, regionally, are some of the biggest contributors of emissions.”

Allegheny County saw concentrations of ground-level ozone pollution fall into attainment of the federal standard a few years ago. Ozone, caused by a reaction of sunlight, heat and fossil-fuel emissions, harms lung tissue and can worsen respiratory diseases, such as emphysema and asthma. Car, truck and bus emissions are among the biggest catalysts.

Pittsburgh Works, an industry and labor group, argues in a recent report that such improvements belie the failing grades the region’s air gets in some national comparisons, such as the American Lung Association’s annual air quality rankings. The group describes the region’s air quality as “more like a “C+ student.”

Unfinished business

Whatever the grade, the region remains a work in progress when it comes to protecting the public from the health risks of air pollution.

Allegheny, Armstrong and Beaver counties don’t meet minimum health standards for the air pollutant sulfur dioxide — something 98 percent of U.S. counties have already accomplished. Emissions trends suggest Allegheny County could earn that status this year, health officials said.

County air quality officials report seeing an increase in the frequency of weather conditions that inhibit pollutants from dispersing, which leads to more intense concentrations and greater health risks.

A new county Health Department rule is expected later this year requiring industry and others to take emergency action to reduce emissions when such days occur. “It’s a similar idea to when we say it is going to be a high ozone day, please don’t refill your car until later in the day or please don’t burn in your backyard until we have better air quality,” said Jayme Graham, Health Department air quality program chief.

And scientists continue to debate whether U.S. air quality standards are as protective of human health as they need to be. “There’s a big gap between regulatory standards and what public health experts determine is a standard that actually protects people,” said Matthew Mehalik, director of the Breathe Project, a coalition of environmental, health and academic organizations.

The EPA’s most recent PM2.5 standard that the county just met, for example, allows for pollution levels 20 percent higher than limits enforced in Canada and recommended by the World Health Organization for all nations.

In an internal analysis of the U.S. PM2.5 standard, EPA scientists last year called into question the protection it offered the public, and presented a case for ratcheting the annual limits down from 12 micrograms per cubic meter of air to 10 or lower to better reflect the public health risk. No change was made. But the new EPA administration is expected to reconsider the growing evidence that suggests lowering PM2.5 leads to fewer deaths, increased life expectancy, lower rates of respiratory disease among children and other health improvements.

Tighter limits on the air pollutant would again challenge the region to come up with new ways to clean the air for better health and quality of life. “As Pittsburghers, we’re proud of the history of innovation in our region,” Mehalik said. “We can find a way to get well ahead of where we are now, instead of being a lagging region on a very important public health issue that’s material to every resident and business in the county.”