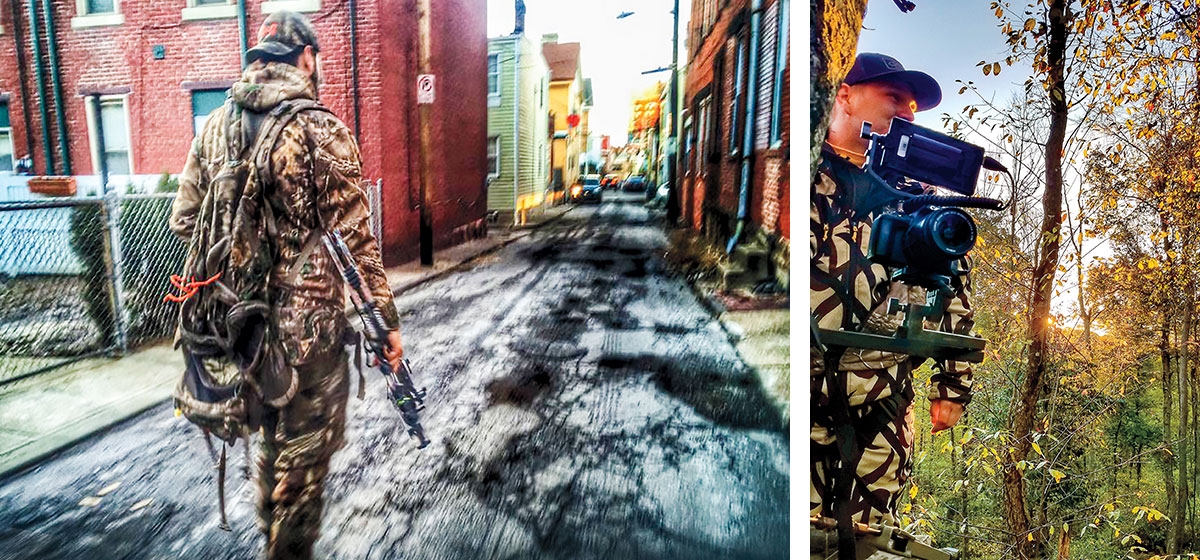

The Urban Deerhunter

Every July, along deer trails in pockets

of forest in and around the city of Pittsburgh, Dan Krivanek and his buddies hang a bevy of camouflaged infrared LED hunting cameras in the crooks of trees. They also strew cut up apples and feed corn. Then, back in his Bridgeville borough home a few miles away, Krivanek waits. Eventually, movement triggers bursts of footage, giving Krivanek a prime view of deer and their feeding patterns.

Among the places he’s hunted is Mt. Washington, a dense neighborhood of some 10,000 people, a clifftop community known for providing prime views of Pittsburgh’s Downtown across the river. As Krivanek said, “We’ve picked up all kinds of stuff up there, including some monster bucks.”

He selects a particular returning doe or buck that he’ll aim to take with his Bowtech Diamond Marquis compound bow (shooting Goldtip arrows with Thunderhead broad-head points at up to 322 feet per second). He maps the best location for his “take and go” deer stand (also camouflaged). When archery season opens each September, a camouflaged Krivanek finds that spot, climbs a tree, chains his stand and takes a seat. Some days, hikers pass directly below Krivanek, unaware that he’s just feet away, bow at the ready.

Krivanek usually kills just one deer a year, enough for his wife and two children to enjoy jerky, ground burgers and tenderloin steaks—always marinated and usually grilled. But he knows some hunters who’ll get up to eight deer in one season.

Unbeknown to many Pittsburghers, hunters like Krivanek are regularly patrolling the city’s wooded hillsides in search of that prized doe or buck. Reporting for this article led to hunters who’d tracked down deer in Arlington, Arlington Heights, Brighton Heights, Bon Air, Carrick, Garfield, Hays, and Mt. Washington. Residents may be surprised to learn that deer hunting within city limits is completely legal.

Krivanek said he closely follows Pennsylvania Game Commission rules. He purchases an annual license and hunts during the designated archery season, from mid-September to mid-January, with a several-week break in December (Pittsburgh hunters may use shotguns for two weeks in December and then flintlock late in the season, though never rifles). He remains the required 50 yards from any occupied structure (150 yards for firearms), and he doesn’t tread on park land or property posting no-hunting signs.

Wherever he sets up, Krivanek remains downwind from his target’s approach.

“If [the deer] smells you in a tree stand, he won’t walk that path. He’s going around you.”

Through his company S City Outdoors, Krivanek trains new hunters to tune and shoot a bow, account for windage, use trail cameras and pattern a deer. “There’s just so much,” he said. “Not a one-day or even a one-year procedure.” He even teaches young people how to climb a tree, “which scares the living bejeebies out of them,” and then shows them how to use a tree harness.

Jeannine Tardiff Fleegle, wildlife biologist with the Pennsylvania Game Commission, said that people “can be taken aback” when coming upon urban hunters, because “there’s a person with a weapon out to actually kill something.” She emphasized that hunting accidents are rare.

In 2018, the game commission recorded just 27 “hunting-related shooting incidents” (HRSIs) statewide and across all types of hunting, including one fatality—an incident rate of just over three per 100,000 hunters. Most resulted in a self-inflicted injury. Incidents have been declining for several decades.

“There is no gray area. It’s either a legal deer, and it’s a safe shot, or it’s not,” said Kendall Pelling of Garfield, who has been shooting firearms since he was a child. “You don’t shoot at a running deer. You don’t shoot at a deer you can’t identify. You don’t take a shot if you don’t know your backstop. You just don’t, because it’s not worth having any risk at all.” HRSIs aren’t accidents, he said, but the result of a bad decision.

Pelling usually hunts outside of the city, but a few years ago he and his brother had permission to set up a stand at an abandoned house in Garfield. After watching several deer pass through the yard one day, his brother used a shotgun slug to kill an eight-point buck. Then, as Pelling and his brother stood astride the carcass discussing their field dressing process, a heavily tattooed and camouflaged man stepped out of the woods carrying a bow.

“Oh, you got a big one!” he exclaimed. He told Pelling that he’d grown up in Garfield and frequently hunted this area of the neighborhood. On this day, he was walking the woods in hopes of driving deer toward family members waiting to take their shots.

“And here I thought like I was doing something extremely rare [hunting in the city],” Pelling said.

Pelling piled the deer into the trunk of his car, drove it home and carved it up in his side yard, hanging the deer from his kids’ swing set.

The Game Com-mission manages hunting in multi-county wildlife management units; Pittsburgh anchors unit 2B, comprising Allegheny County and minor portions of surrounding counties. During the 2018–19 season, hunters took about 17,000 deer in 2B and 375,000 statewide.

No agency tracks the number of deer hunted within Pittsburgh or even how many live in the city. The Game Commission describes the 2B deer population as “stable”—neither increasing nor decreasing significantly.

Still, David Costa of Brighton Heights said he sees a “ton of deer” near his home. “I can basically walk out of my garage and walk down the hillside,” he said, choosing some days to bow hunt in a nearby ravine rather than making the long drive to hunting grounds outside the city.

John Hancock also sticks close to home, hunting regularly on his own property running along the northern edge of Northview Heights. He generally gets two deer each season, he said, though he’s taken up to five. “I have these deer running all over my property eating my garden. So, I shoot them, I butcher them, and I grind them into sausage every year.”

Hunters are among the few predators that keep area deer populations in check. In the past, coyote, bear and bobcat preyed on more area deer. Now, though, “it’s either hunting or Hondas,” as Pelling put it. The Pennsylvania Insurance Department recorded 909 deer hit in Allegheny County between 2012 and 2016, more than any other Pennsylvania county.

In Pittsburgh’s 259-acre Riverview Park, an overabundance of deer have plundered saplings and small plants (deer can eat vegetation up to at least five feet high). This has led to an imbalanced ecosystem and made the park susceptible to overgrowth of invasive plants and other intrusive species. As a result, the natural plant understory has mostly disappeared, which in turn leads to erosion.

Park Ranger Nancy Schaefer said she finds it can be “frightening to be in this park” during rainstorms when “brown rivers of soil are washing out of the park on all sides.” Riverview is partnering with the Pittsburgh Water and Sewer Authority and Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy to restore the ecosystem, in part by building deer exclosures—large fenced areas that prevent deer from over-feeding fragile flora. Increased plant growth also will decrease the amount of rainwater rushing into the city’s overburdened combined sewer system.

However, these measures don’t directly address the deer population.

“The long-term solution is, you need to kill more deer,” said Timothy Nuttle, senior ecologist with Civil & Environmental Consultants, who has researched Riverview’s deer population. He estimates the herd size to be about 60 deer per square mile, but in order to allow for plant regeneration it should, in his view, be reduced to about one-third of that figure. Hunting in city parks is illegal, though the city could permit controlled hunts by offering a limited number of archery permits, for example, or by hiring sharpshooters. As an alternative to killing deer, they could be captured and sterilized, though this approach is much more expensive. Pittsburgh does not currently have a deer management program.

Brenda Smith, executive director of Nine Mile Run Watershed Association, said Frick Park also has a deer problem. “I really feel like the city government should be doing something to at least assess the problem,” she said. She noted that a deer stand was discovered in the park last year. “It really brought home the need for the city to more actively address this problem. There’s just no getting around that being a dangerous situation.”

According to biologist Tardiff Fleegle, there’s no set determinant for how many deer are “too many.” When setting management goals, the Game Commission considers forest habitat health, deer health, and deer-human conflicts, the latter being a particularly important factor in urban areas.

“Tolerance” can therefore vary by community and lead to a patchwork of approaches to population control. In recent years, some area municipalities—including Fox Chapel, Upper St. Clair and Mt. Lebanon—have implemented culling programs using controlled archery or sharpshooters. In some townships, public meetings have yielded heated debate. “I would love for there to be a more collaborative deer management approach in the city and urbanized areas,” Pelling said. “To plan out the places that are safe, appropriate … for licensed, regulated hunting.”

Riverview’s Schaefer noted that many people enjoy the presence of deer as a close brush with wild nature. Though Schaefer discourages park goers from feeding wildlife, one resident told her that he spreads 50 pounds of feed corn around the park every week in order to attract deer.

For some, hunting deer leads to both a brush with nature and peace of mind. “That’s my meditation time,” said one hunter in Arlington Heights. “I go hang out, meditate. If something happens to walk by, maybe there’s a little meat on the table. But for me, it’s just about being out, watching the birds, meditating and just chilling out.”

Lucas Austin of West Deer Township agrees. He prefers rural hunting that allows him to “sit in tree and be peaceful, hear nature, not see cars.” He said that in the city he comes upon littered hillsides and more noise and people. However, as archery season comes to a close each year, if he and his friends still have unused tags, “It’s time to round up the boys and we head south to the city. We do well every time,” he said, describing the trip as “our end of the season hoorah.”

After the party chooses a location, one hunter—the “pusher”—will begin walking in one end of the wooded area and flush deer toward several waiting “shooters.”

“I mean, it only takes minutes when you’re in the city,” Austin said. “The woods aren’t too big, dude … The amount of big bucks that come out of that city would blow your mind.”

According to Austin, the bows and other gear are a “red flag” for some city residents. But he finds that encounters with other people in the woods become teaching moments. “So that side of it’s cool, too—when you get to talk to people, let them know what we’re doing.”

Asked where exactly he hunts in the city, Austin simply said, “Every year we find some new patch.” Most hunters interviewed for this story declined to cite specific locations, only naming a neighborhood or general area. Krivanek, pointing out that tracking deer and a good location for his stand requires a lot of work, remained equally evasive.

“It’s almost like a secretive tradition or a secretive trade.”