You’re in ‘Steelie Country’

When summer gives way to early fall and warm days yield to cool nights, an annual obsession begins to surface on Lake Erie streams.

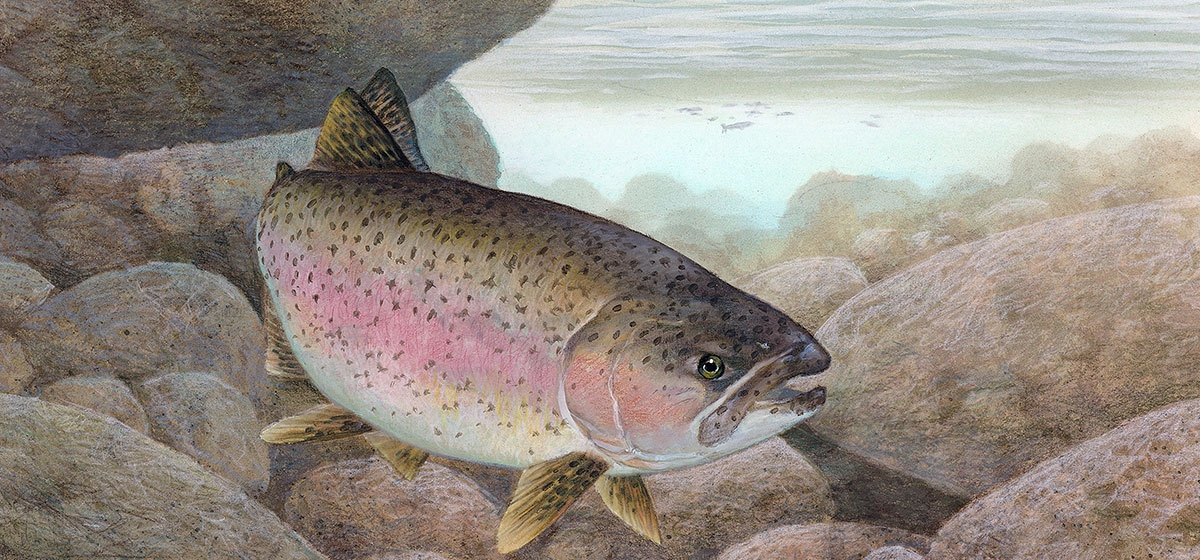

Steelhead and those enamored of the silvery salmonid (Oncorhynchus mykiss) migrate en masse to dozens of tributaries in Pennsylvania, Ohio and New York. Anglers wade knee-deep into the chilly, slate-blue water and cast wooly buggers, sucker spawn and other flies with funny-sounding names, or live Emerald shiners—Erie’s main forage—in the hope of doing battle with the charismatic trout.

Spurred by instinct, lustrous males with crimson stripes and egg-laden females make arduous journeys to the place where they were stocked as six- to seven-inch yearlings. As they surge against the current, intent to spawn, those that slam a fisherman’s hook promise rocketing leaps and tail-dancing runs.

It is an encounter thousands of anglers cannot get enough of. “It’s a sickness,” said Matt Hrycyk, with a wry smile, of the mania that keeps Poor Richard’s Bait and Tackle open 18 hours a day during steelhead season. “Our phone starts ringing after the first couple of cool nights in August, and never stops, with guys asking, ‘Are they in yet? Are they in yet?’ ”

“Pound for pound, steelhead are some of the strongest, fastest fish you’ll ever catch,” said licensed steelhead guide Mark DeCarlo of Indiana, Pa., who has landed and released “steelies” up to 14 pounds on Elk Creek, one of Erie’s larger streams. “This is the closest thing to Alaska salmon-fishing most folks around here will ever experience. A lot of people who’ve done both say Erie steelheading’s just as good, at a fraction of the cost.”

In fact, steelhead and the Coho and Chinook salmon the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission also once stocked have origins in the Pacific Northwest and were introduced to the Great Lakes in the late 1800s. The commission stepped up its steelhead stocking program in the 1960s because steelhead promised the biggest bang for the buck. “Salmon die on their first spawn, so it was a lot more expensive to keep that program going,” said Chuck Murray, the commission’s Erie biologist. “Steelhead can spawn and return to streams multiple times, and their eggs are much more viable.”

Fifty years ago, 15,000 hatchery-bred “steelies” seemed like a lot. Today, the commission stocks more than 1 million steelhead in a dozen tribs annually in what has become the state’s most successful artificial fishery. Although the commission spends more than $1 million a year on its Erie steelhead program, without this effort, the fishery—and the $9 million in recreational tourism it has spawned—wouldn’t exist. Unlike streams in Washington’s Hoh, Sol Duc, and Calawah watersheds, Pennsylvania tributaries become too warm to sustain salmonid fry.

“The eggs hatch, but when streams hit 80 degrees, it kills them,” Murray said. “A few tribs with spring-fed seeps, like Trout Run, Raccoon and Conneaut, are believed to support a little natural reproduction, but even in a good year, it only accounts for 2 to 5 percent of the overall fishery.”

The majority of steelhead are born and raised in state hatcheries, where culturists create life by mixing eggs and milt (sperm) from brood stock collected on select streams. Eggs are disinfected, incubated until they hatch, and then raised for a year before they are “planted” in tributaries in early spring.

A potamodromous species whose migrations occur wholly within freshwater, Erie steelhead spend summers in the open water—where anglers catch them by down-rigging in the deepest part of the lake—and make exploratory spawning runs to tribs in fall, beginning when they are two or three years old.

“They cue off flow, water temperature, and changing day length,” said Murray. “They’ll ‘stage’ at the mouths of the creeks, and when all of those elements are right, they’ll move into the tribs, going as far upstream as water levels will allow. In low flow, they’ll stick to the lower reaches of the streams, and when it’s high, they’ll move upstream. Our longest trib, Conneaut, is 43 miles, which a steelhead could easily travel in a weekend, and maybe even in a day.”

Runs typically peak in November, but anglers who can’t wait are willing to stand elbow-to-elbow at the lakefront and cast glittery spoons to steelies staging in the surf as early as September. Lines tangle and tempers flare as they vie for the season’s first catch.

“It’s combat fishing, but I think some guys actually like it,” said DeCarlo, who guides clients away from crowds, although it is becoming more difficult to find free fishable water. The boon in steelheading has triggered a battle over shrinking access.

Landowners fed up by large and sometimes ill-mannered crowds are posting their property, while those eager to make a buck are leasing to private fishing clubs, or selling easements to the fish and boat commission. On Erie’s non-navigable waterways, riparian landowners control the streambed adjacent to their property and can prohibit anglers from wading through “posted” sections. Perhaps the best-known of the pay-to-play bunch is the HomeWaters Club, the former Spring Ridge Club that was successfully sued by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 2007 for trying to deny public access on the Little Juniata River in the central part of the state. Club members pay tens of thousands of dollars for the exclusive use of streams in Erie and elsewhere.

But while privatization may be a sign of the times, many find it an affront to a fundamental American tradition: knock on a door, ask permission to access a stream, and leave a nice fish as a token of thanks on the way out.

Bob Hetz, 75, has lived all of his life on Trout Run, and helped found a series of non-profit nurseries that raise supplemental steelhead for the fish and boat commission through the all-volunteer 3-C-U Trout Association. “It’s OK for people to post to ‘no fishing,’ ” Hetz said, “but to make money off of fishing is a problem. It’s wrong.”

Steelhead guide and author John Nagy of Brookline agrees. “Every youngster should be able to fish a stream without their father being a member of a fishing club that excludes the public and caters to the wealthy, the elite,” said Nagy, whose “Steelhead Guide: Fly Fishing Techniques and Strategies for Lake Erie Steelhead” is now in its fourth edition. “If we don’t work to keep more streams open—and time is of the essence—we’re going to slip into privatization and that will be the end of fishing as we know it.”

Nagy called the fish and boat commission’s recreational easement program the saving grace of Erie steelheading. So far, the agency has spent almost $2 million to keep 15 stream miles open to public fishing. The program is funded by the sale of special stamps to more than 110,000 of the state’s 840,000 anglers.

“We’ve sold licenses to people from most states and many countries, from Canada to Kentucky,” said Poor Richard’s Hrycyk. “On any given weekend, you’ll see cars along the tribs from everywhere.”

Anglers of all skill levels target steelhead, using live bait, skein removed from gravid females, or subsurface flies tied from yarn, feathers and fur to imitate baitfish (streamers), larval insects (nymphs), or salmon eggs.

While the traditional technique is to dead-drift a nymph along the bottom of the stream, finessing it so it moves naturally in the current, in the past five years, a fly-swinging technique from the Pacific Northwest has gained momentum in Erie. “Swinging puts movement and speed on a fly, so it goes across and in front of the fish,” Nagy said. “When a steelhead hits that, it’s—pow!—like getting mugged.”

Fish caught on swung flies tend to be the freshest, strongest and most aggressive, he said. “They’re top-of-the-gene-pool gorgeous, not a mark on them, whereas when you nymph, you may catch more fish, but you’ll get the variety, including the old, tired, lethargic fish beat-up from migrating on shale.”

Nymphing is more effective when tribs dip below 40 degrees and steelhead won’t work for food, he said. “Swinging is productive when water is a little warmer and fish are more active. It’s good to know both techniques.”

The largest steelhead known to have been landed in Erie was a 20-pound three-ounce behemoth that nabbed the state record on Walnut Creek in 2001. Last year, the largest steelhead reported was a 34-inch, 16-pound six-ouncer with 18-inch girth, landed on a minnow on Twenty Mile Creek. At 10 pounds, a steelhead has trophy status.

Although anglers are allowed to keep three 15-inch or longer steelhead a day from September through April, some think it’s time for the commission to reduce creel limits, given the pressure on streams. “There’s a lot of steelhead being killed,” said DeCarlo, who urges clients to follow a catch-and-release ethic. “Steelhead are a strong-tasting fish, not even that good to eat. Folks who want to get a fish mounted should consider a replica. They’re as nice these days as the real thing.”

Illegal catches also take a toll, with organized poaching rings netting or snagging a bounty of steelies for sale on the black market.

Steelhead numbers are influenced, too, by what happens in the main lake. When walleye abound, steelhead populations drop, since young steelhead (smolts) are walleyes’ favorite forage. Cormorants and herons also can be seen feeding on smolts at the mouths of the tribs.

Despite all of these influences, though, Murray said there’s no biological need to tighten harvest limits on steelhead. “It’s not that delicate of a fishery and our studies show most folks practice catch and release or keep just one fish. Of course, there’s a social side to fisheries management, and that’s a whole other story.”