Who Quotes Nero?

Poems have birthdays but no funerals. They somehow manage to outlive their creators as well as the times and cultures in which they were written. Why? How?

Numerous answers have been given—some academic, others pedestrian, and still others with silence and a shrug. The common theme that appears in these various answers is that poems or poetic moments in conversation or speeches live on simply because they do. It comes down to memorability. Poetry lives on in those who are affected by it because they cannot forget it even if they try.

Here is a poem that was composed by an Egyptian girl to her beloved in 1500 B.C. Even in translation it has a vibrancy that it must have had 29 centuries ago.

O my beloved

how sweet it is

to go down

and bathe in the pool

before your eyes

letting you see how my drenched linen dress

marries

the beauty of my body.

Come, look at me.

Some say the poem has endured simply because of its imagery of desire, nothing more. Really? But what of those poems that have nothing to do with love or desire and yet are still with us? Here is a poem from the Greek Anthology translated by Richmond Lattimore. It is one line long and sounds as if it were spoken by a minor military officer who is desperate and surrounded by listless soldiers awaiting orders.

Erxias, where is all this useless army gathering to go?

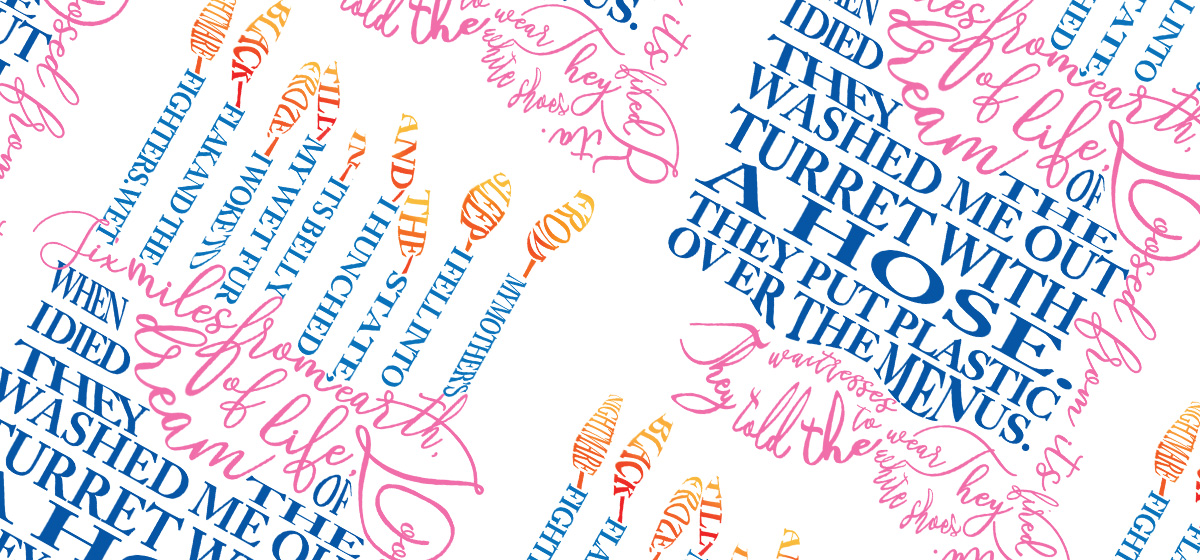

War has received similar cryptic but equally memorable treatment in our own era in Randall Jarrell’s “Death of the Ball Turret Gunner.” The ball turret on a B-17 was located on the bottom of the fuselage. It was the first target of enemy fighters attacking the B-17 from below because killing the ball turret gunner would leave the bomber defenseless. It was estimated that the life of a ball turret gunner in battle was approximately 18 seconds. Here is Jarrell’s terse epitaph:

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

I have chosen these three examples at random to demonstrate that memorability does not derive from the subject but by how the subject is poetically seen and presented.

In the saga of Christianity there have been as many derivations of its true meaning as there have been sects and traditions. To some it is a belief in a life to come for the few (the Elect) who have been predestined to be rewarded. To others it is the image of the crucified Christ—an all-too-common prefiguring of the very nature of human life with too little emphasis on grace and redemptive suffering. To Paul of Tarsus it was an invitation to give and accept love every day. He said so in the First Epistle to the Corinthians in words that not only capture but seem to ensue from the very essence of love that most people would affirm. “Yea, though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels and do not have love, I have become like sounding brass or a tinkling cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy, and know all mysteries and all knowledge; and if I have all faith so as to remove mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. And if I give all my possessions to feed the poor and surrender my body to be burned, but do not have love, it profits me nothing. Now there abide faith, hope and love, these three, but the greatest of these is love.” It is not only the conciseness of the language but the imagery and rhythm of the lines that focus and overwhelm the reader, and it is that art and skill that make Paul’s words memorable.

It all comes down to language, the way something is said that is an exact fit for what is meant. It is felt speech. For me one of the best examples of poetic exactness is a short poem by the current poet laureate of Arkansas, Jo McDougall. The title of the poem is “When the Buck or Two Steakhouse Changed Hands.” It is a classical example of what happens when a neighborhood lunch room or restaurant is taken over by a national franchise.

They put plastic over the menus.

They told the waitresses to wear white shoes.

They fired Rita.

They threw out the unclaimed keys

and the pelican with a toothpick

that bowed as you left.

I have quoted this poem to friends and strangers on numerous occasions. Every time I finish the third line, I look and see smiles. The smiles tell me that every independent lunch room has its “Rita.” She takes the orders, chats familiarly with customers, brings glasses of water without being asked, makes the lunch room feel like home and helps out at the cash register. That reference to Rita and what it implies in a single line create a universal portrait.

These are but a few examples of poems or poetic passages that always create a sense of eternal presence. And those, like me, who often quote them to others perpetuate that presence by doing so.

With literature, as with all the arts, time eventually separates the wheat from the chaff, and what is best endures. The endurance is not commemorative but actual so that the language is as alive as when it was spoken or written. Such language mocks time, which dates every other aspect of life but that. Consider the following three examples. Dead at 52, William Shakespeare lives on in his poetry and the poetic diction of his plays. They have reached millions in multiple countries for over six centuries. Reading a sonnet by Shakespeare or attending one of his plays is not a matter of nostalgia but an experience in the present tense. The words have long outlived the life of their author. The same can be said of the poems of John Keats, who lived only into his twenties. And then there’s Robert Frost whose life in decades topped them both and whose poems will certainly exceed his 89 years on this planet. The words of all three of these poets are being quoted into life by someone somewhere even as I write these lines, and that attests to what can only be called their immortality.

The difference between immortality and mere fame or historicity is reflected in the difference between the truly poetic, which is dateless, and that which is confined to dates. If I were to quote Robert Frost’s “Two Tramps at Mud Time,” the poem by the power of its theme would not end where it stops; the implication of its theme would simply keep widening. Here’s how the poem ends.

But yield who will to their separation,

My object in living is to unite

My avocation and my vocation

As my two eyes make one in sight.

Only where love and need are one,

And the work is play for mortal stakes

Is the deed ever really done

For heaven or the future’s sakes.

The same guarantee of deathlessness could not be said of others whose names are as well known as Frost’s. Who quotes Nero? Who even wants to? Who quotes Genghis Khan, Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler or Al Capone with anything approaching what makes them revere and even commit to memory words they want and need to know by heart?

I’ve noticed the same inclination in the attitude of literate citizens toward politicians they admire. Abraham Lincoln’s 272 words at Gettysburg not only defined the very idea of democracy but did it so well that they seem beyond improvement. They are engraved not only at Gettysburg but in the hearts and minds of millions of Americans.

Everyone remembers President Franklin Roosevelt’s “We have nothing to fear but fear itself” and his subsequent “Day of Infamy” speech after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Apart from the forensic fact that Roosevelt was a consummate orator, the words in their very brevity captured what a prolonged appeal to hope and solidarity would have blurred. Taken to heart with similar zeal was John F. Kennedy’s “Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country.” (At his own inaugural, Richard Nixon eight years later made a self-revealing and predictable change when he altered and debased the line with his own bias to read, “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for yourselves.”) Memorable as Kennedy’s original statement was, his speech at the Dáil when he visited Ireland in 1963 was for the Irish unforgettable. Summoning his link with his forbears from County Wexford, Kennedy at one point recited a verse from a ballad that glorified the resistance of the Irish to British suppression during the “troubles.” What made it even more germane was the presence of Eamon de Valera in the audience, the only one of the Irish resistance leaders who was not executed by the British.

We are the boys from Wexford

Who fought with heart and hand

To break in twain the galling chain

And free our native land.

De Valera and all those around him gave the lines the ultimate applause of reverent, sustained silence.

Language that can actuate the imagination while simultaneously stirring the feelings is language that cannot be ignored. The words are felt, and it is the author’s intent and hope that his readers or hearers will feel what he feels. A poet, for example, might caution those addicted to globetrotting by saying as a matter of fact that anywhere they go will become here as soon as they get there. Or the same poet might say to old widowers, who think they will regain their youthful vigor by marrying younger women, that they just might feel even older after they did it. Obviously true, but memorably said…

It has been my experience that it is with children that some of the most memorable words are spoken. Here are a few that I’ve listed over the years, and I will conclude this brief essay by letting them speak for themselves.

Once my brother-in-law was playfully holding his 6-year-old daughter by the ankles to keep her from moving. Frustrated and knowing that she could not free herself, she said sternly, “Daddy, please let go of my wrist-legs.” Another totally different but memorable response came to my son, who is a composer and conductor, from a handicapped girl in a high school orchestra when he asked her why she liked music. After a moment, she said, “I like music because I can make it.” There was another instance when a young boy and his mother were listening to a weather report on television. It was predicted that there would be a drop in temperature that would be caused by the “wind chill factor.” The boy turned to his mother and asked, “Why is it always colder in the windshield factory?” Several decades ago my sister-in-law, who was expecting her third child, was packing a small bag with personal items to take with her to the hospital. Her first son watched and asked her where she was going. “I’m going to the hospital to get your brother.” After a brief pause her son asked, “How did he get there?” There was a moment I experienced while watching my son as a boy bouncing a ball on the driveway. “Look, Dad,” he said and kept bouncing the ball, “I’m making the ball happy.” And finally there was the time that our dog Oscar died. He was known to and loved by all the children in the neighborhood. Several days after he died one of the neighbor’s children approached me on the front porch and asked, “Where’s Oscar?” I said that Oscar had died. “When is he coming back?” I explained that Oscar had died and gone to heaven, and that those who have gone to heaven don’t come back. The child waited and then asked, “Is Oscar in jail in heaven?”