Spring brings warblers! It’s that simple. Spring, longed for after the buffeting chill of winter, gives way to warmth and light… and birds. Birds by the millions feel the instinctual pull north every spring, and we who await their passage are rewarded with color and song.

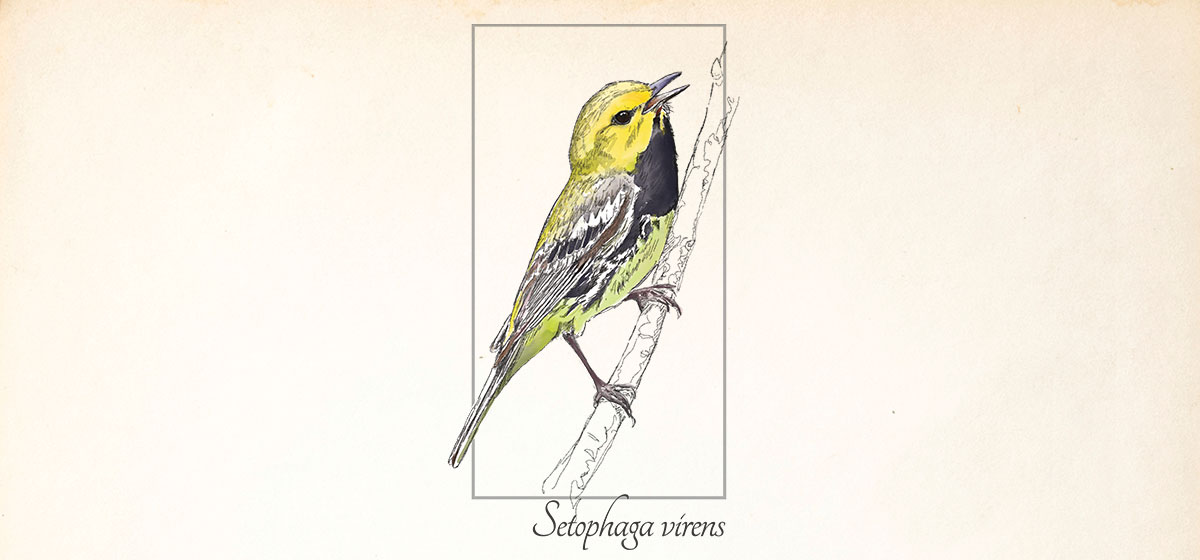

One of my favorite species is the black-throated green warbler, a common migrant, engaging songster and successful breeder throughout vast swaths of the commonwealth. Easier to hear than spot at first, the song of the bird—a high, somewhat raspy zoo-zee-zoo-zoo-zee—is a fantastic bit of avian music to commit to memory in winter as anticipation for the first living singers of spring builds.

Zoo-zee-zoo-zoo-zee. Another, more memorable transcription? Trees, trees, I love trees. Either way, there’s nothing like it until your ears have been dazzled by the living, feathered thing. Then it’s as if you’ve become aware of something that’s been hidden in plain sight, waiting to be discovered. In migration, black-throated greens might be found high or low, in an evergreen or hidden among the gold-green leaves of spring, but never at a feeder. The birds’ coloration—a combination of green, yellow, black and white—will be sure to present inexperienced birders with the cryptic puzzles that make warbler identification so initially challenging, then immensely satisfying.

Like most warblers, black-throated greens stream north following insect hatches that provide their food. No insects, no feasts. Females pick locations up in trees that hold their small stick and bark nests, some four inches around and two inches tall, built in a week or less. There, three to five white eggs with speckles or blotches hold the next generation, hatched after 12 days of incubation and ready to fledge in about the same period of time after breaking out nearly featherless into the world.

Some 350,000 black-throated green males are estimated to breed in Pennsylvania’s late spring and early summer. The species prefers interior coniferous forests, especially those replete with stands of eastern hemlock. Recent infestations of hemlock woolly adelgid, a nasty invading insect, have done damage to the trees preferred by black-throated greens, as has the fragmentation of forests due to human activity. Climate change may also affect the hemlock, so the birds will have to adapt or see their numbers in our area decline.

There are many places to hear and see these welcome visitors. A reliable spot is Beechwood Farms Nature Reserve in Fox Chapel, the headquarters of the Audubon Society of Western Pennsylvania. Their property in Sarver, called Todd Sanctuary, is another beautiful spot for warbler watching this spring. You’ll definitely see birds and probably make some new acquaintances. Or join an excursion with the Three Rivers Birding Club (www.3rbc.org) or our good friend Bob Mulvihill at the National Aviary (www.aviary.org). Farther afield, I suggest new and experienced birders alike consider attending the Biggest Week in American Birding (www.biggestweekinamericanbirding.com), May 8–17, 2020 in northwestern Ohio. Days of warblers-a-go-go, birding seminars and ornithological camaraderie freely shared await. No matter what, get out this spring to see warblers! Email me your encounters, photos or questions at PQonthewing@gmail.com.