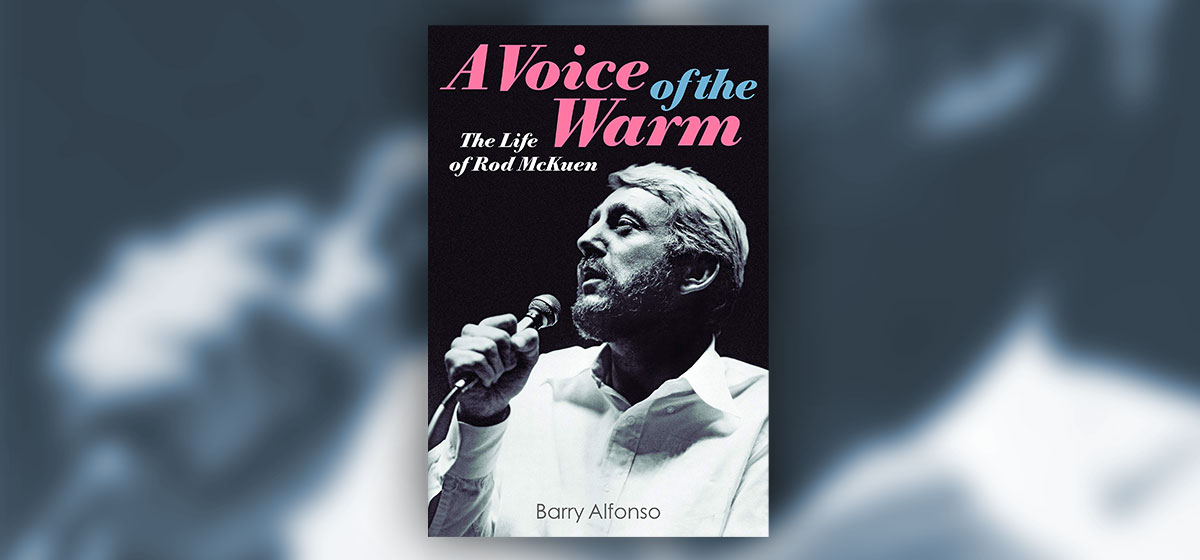

What the World Needs Now… Is Rod McKuen

Barry Alfonso, a writer living in Swissvale, has produced a book we didn’t know was needed. Chances are, if you remember Rod McKuen, you’ll know his popular image: a 1960s California pop singer-songwriter who also churned out best-selling volumes of poetry that non-best-selling poets considered the equivalent of Muzak. Indeed, Alfonso cites the assessment of McKuen’s work by one snooty critic: “a social plague.” To add insult, when McKuen died in 2015, the first sentence of his Associated Press obituary called him “the King of Kitsch.”

“A Voice of the Warm” may not win over the sneering snobs. But that’s not the primary mission of Alfonso, a multi-faceted writer, music critic and historian. He has a great American story to tell, and he tells it with precision, authority and grace. He appreciates McKuen’s body of work, but never comes across as besotted fan.

Born in 1933, McKuen came from a childhood of poverty and transience in Western states, with an unknown biological father and an abusive stepfather, plus a stint in reform school. The absence of stable love gave him a burning yearning to find it. Music and poetry were his vehicles. Through pluck, guile and undeniable talent, by 1971 he was earning $3 million a year. A lot of people liked what he was saying and selling.

Alfonso also makes the case that what the world needs now is Rod’s sweet love. “We live in a time drenched in irony and fearful of expressing genuine sentiment,” he writes. “Rod tried to touch the chords of emotion directly, without apology.” Rod McKuen was also ahead of his time in the sexual identity department. He’s well known for saying, “It’s not who you love or how you love but that you love”—a crowd-pleasing sentiment in the era of hippie universal love, but also an accurate reflection of his discreet life as a gay man who maintained deep emotional relationships with women.

As with any important American story, there’s a Pittsburgh angle. One of the pivotal episodes in McKuen’s life was enabled by Hale Matthews, a Broadway producer and arts patron who was the son of a wealthy Pittsburgh industrial executive. Matthews maintained a vibrant salon in his swanky Upper East Side apartment. Living in New York in the early 1960s, McKuen was a regular attendee, mingling with folks like Bobby Short (and, Alfonso notes, the young wealthy Pittsburgher Richard Mellon Scaife). At one soiree, McKuen met the worldly and well-traveled Ellen Ehrlich. She became his chaste soulmate and was “crucial to Rod’s growth as an artist,” introducing him to the work of Jacques Brel. Year later, the French-Belgian singer-composer and McKuen had a rich artistic collaboration—just one example of the dimensions of McKuen’s creativity that his critics overlook.

“Rod’s sheer tenacity and chutzpah impressed me,” Alfonso writes, explaining why he took on the years of research behind this book. “A Voice of the Warm” should open up a new appreciation for McKuen’s very American life.