On a warm April evening, my son and I went Downtown to meet a friend who is alarmed by what Downtown is becoming. Before dinner, we walked around one block, essentially Sixth Avenue to Wood Street to Liberty Avenue to Smithfield Street and back down Sixth Avenue. On Liberty, a group of young people in bandana masks smoking pot largely blocked the sidewalk. As we sought to walk around them, a tall young fellow who was entertaining the group backed into my friend. He then yelled at and insulted my friend, who’s in his late 60s.

I instinctively said to the kid, “What did you say?” He looked at me, then turned away. My son later admonished me, saying the kid could have pulled a knife or a gun. I said I wasn’t worried about that. But in fact, the next night two people were stabbed a block away.

Thirty feet later, an old, intoxicated guy asked us for money. We briefly chatted with him about Downtown before turning onto Smithfield Street where emergency vehicles with flashing lights were parked in front of the Smithfield United Church of Christ. It wasn’t easy to tell exactly where the problem was. A crowd of 30-40 people milled around, some buying drugs in obvious open-air transactions. To the left of the church, in front of Wiener World and toy store S.W. Randall, others staggered, barely able to stand. Right in front of the church, a guy was smoking something from a silver pipe in his car. Used needles littered the sidewalk.

Beyond that throng, we saw that a man of about 50 was overdosing, and EMS teams were trying to convince him to accept medical help.

The church’s homeless shelter is the focal point for Downtown’s drug, homeless and criminal activities. Its denizens sleep there at night, and during the day they hang around nearby — in the Carnegie Library next door, or they cross Sixth Avenue at Brooks Brothers to Mellon Square Park in front of the William Penn Hotel. They return when the shelter doors open again in the evening.

The one bright spot of our little tour was a friendly, articulate Downtown Ambassador, who was trying to help the paramedics and the OD’ing guy.

***

Among the early stories I covered as a cub reporter was a 1986 arson fire that burned down Dutilh Church, in then-rural Cranberry. The steeple lay on the ground and there, amid the charred ruins, I first met Doug Patterson, a young pastor vowing to rebuild. We kept in touch, maybe every 10 years, largely because of a shared interest in the homeless. I contacted him in April after my recent Downtown walk to get his take on the situation and the shelter at Smithfield United Church of Christ, where he’d been lead pastor for the last 25 years until he retired last fall.

He said the shelter goes back to the late 1970s when it was originally Bethlehem Haven, a shelter for women. “When Bethlehem moved to a different location (in 2000), the county came to us and said they needed a place to shelter some of these guys in the cold weather.” Last year, Allegheny County told Patterson it wouldn’t need the county-subsidized church shelter any more after the new Second Avenue shelter opened late in the fall. “Well, that didn’t work out,” he said. “The new shelter can handle 130 people and it’s filled.”

Patterson had tried to make a difference. “I’ve served on all the boards regarding homelessness for the last 25 years. The problem’s worse than it’s ever been, and my take is it’s not because of a lack of money. There’s no communication between these agencies and offices. It’s confusing and maddening. They get angry with each other. It’s just a bunch of groups trying to do their own thing, but no coordinated effort from the city or county. As I told a colleague years ago, if you put out saucers of milk, don’t be surprised if every feral cat in the neighborhood comes.”

My own interest in homelessness goes back to July 1988, when I spent 14 days and nights living on the streets of Pittsburgh disguised as a homeless man. I slept in shelters and parks and hidden, unusual places where I thought I’d be safe. I wrote a six-part newspaper series about it, which got tremendous attention. And on and off for the next 25 years, I tried to help two homeless guys I’d met. I saw it as a duty, albeit an exasperating one because my efforts were largely futile.

Visitors, residents and businesses alike are calling for action to address and solve Downtown’s problems.

What’s happening now in Downtown Pittsburgh is different. Back then, as now, drugs, alcohol and mental illness accounted for roughly three-quarters of the largely docile local homeless population. Now, though, it’s not just the homeless. Now there’s also an overtly aggressive criminal element who increasingly see Downtown as their turf, where they can enjoy doing and dealing drugs and intimidating others with apparent impunity.

***

Since early March, I’ve been meeting with people about Pittsburgh as part of the Pittsburgh Tomorrow project (see story on page 24). The stories I’ve heard about Downtown and the things I’ve seen, including men exposing themselves as women walked by, are certainly disturbing. More than that, however, they are an outrage — a slap in the face to the generations of Pittsburghers who have built the relatively compact Golden Triangle into Pittsburgh’s showpiece. Longtime businesses are shutting down and moving out. How long will Brooks Brothers, Wiener World and S.W. Randall stay if the city doesn’t clean things up? The Parks Conservancy staff don’t feel safe cleaning Mellon Square Park, and one can only imagine what visitors staying at the William Penn think of Pittsburgh.

I don’t really blame the homeless, addicted, criminal opportunists or young hooligans. They are being allowed to gain a significant foothold Downtown. In my view, the onus at this point lies with the public officials whose job it is to face and solve such problems.

Many of the Downtown residents I spoke with — all are community leaders — say there’s “bad blood” between the police and mayor’s office, that police say they have been told not to arrest people, that they should leave the homeless, drug addicts and dealers alone because the mayor’s office doesn’t want Downtown crime stats to rise. It’s hard to believe that’s true. But it’s difficult to know what’s accurate because the Mayor and his staff are remarkably unresponsive to the press.

***

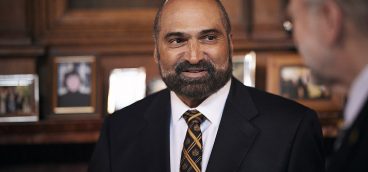

On April 27, I went to the Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership annual meeting. I’d been to the event once before, maybe five years ago, and was amazed at the turnout of more than 1,000 people. They came for the meeting but mainly for the party afterward. It was the place to be.

This year, I went again, curious to see what the listed speakers — Mayor Ed Gainey, County Executive Rich Fitzgerald, and PNC CEO Bill Demchak — would say about the state of Downtown. I expected a kind of call to arms, perhaps a coordinated statement about imminent actions that local leaders are taking to turn around the mounting disaster that Downtown is becoming. At the least, I expected a show of real concern and acknowledgement that the Golden Triangle is becoming anything but.

Instead, what I and the crowd of maybe 250 heard was a series of feel-good platitudes from the politicians. Absolutely no sense of urgency. They did acknowledge that Downtown wasn’t what it used to be, but they intimated that it really isn’t that bad, and the problems are being addressed. The crime is exaggerated, one said, and, after all, urban centers across the country are having problems. So what do you expect? And perhaps, as politicians, they can be excused at such a gathering for putting an upbeat spin on Downtown despite the facts.

Demchak, however, didn’t play along. He cut through the blather and pointedly said, “Coming Downtown is a choice. You have to make it be a place where people want to be — you have to make it easy. And today it isn’t easy. It’s a difficult conversation, but we need to have that conversation.” I gave him a standing ovation, the only one in the room to do so, because he was the only speaker until that point who said anything real.

After that meeting, my son and I walked back to our car, taking a detour through Mellon Square Park. That park, however, is now overrun by drug addicts and surly-looking vagrants or worse. I’m 6’1” and 200 pounds and I’ve made my way through Downtown for decades and have spent time among similar groups more than most, generally without concern. Instinctively, however, this group felt more threatening, so we left the park.

As we approached the car, looking down one alley, a man was openly urinating (see photo). Two minutes later, as we drove by another alley, another man was openly defecating. Turning onto Liberty Avenue, groups of what the mayor earlier had called “children” were standing around blocking the sidewalk — most wearing bandana masks and bothering passersby, one of whom was a young nurse, and another was a father walking with his very young son.

***

Downtown has never been worse — never been anything close to this in the 38 years I’ve been here. And yet, to me at least, it doesn’t seem like a problem that’s terribly difficult to solve. We’re not like other cities — Portland, Chicago, San Francisco, Seattle, and Baltimore — and we don’t want to lose control of our Downtown — as they have. So why are we tolerating what’s happening?

The Golden Triangle isn’t that big. And it’s not that difficult to imagine what needs to happen and then to make it happen. Pittsburgh’s homeless population also isn’t very big. Yes, we need services for them and for those with mental health problems and drug addictions. However, allowing them to make the heart of the Golden Triangle into a place of human filth, drug-dealing and depredation is unacceptable.

They’re currently camped out all around Downtown and along our formerly nice riverfront trails. If we want to relocate them, how about building them a new place to go with services?

Buy some land on West Carson Street, across from the point, just west of the Fort Pitt Bridge. It’s not residential and it’s walkable from Downtown. How about building facilities there with bathrooms, showers and overnight accommodations?

After community pressure, police presence Downtown has increased, but obviously, it hasn’t solved the problem. How about arresting the drug dealers and marauders and letting them know they have to obey the law in the Golden Triangle? Use some plainclothes officers and simply get it done. Get serious before more damage is done. People have to feel safe coming to work, the Cultural District, and Downtown restaurants.

Unfortunately, increasingly in this country, we can’t count on elected public officials to actually lead. That’s the case in the city of Pittsburgh now. And county government isn’t filling the void.

At some point, however, it’s not enough to complain and say the emperor has no clothes. At some point, if the public sector won’t do their jobs, the private sector has to play a more prominent role.

Step one is letting city and county leaders know, loud and clear, that it’s time they work together and take action.

We can’t allow the Golden Triangle to become a cesspool. The centerpiece of this region’s past, present and future is Downtown Pittsburgh.

(Editor’s note: This story was written and in production weeks before Allegheny County’s decision to close the homeless shelter on Smithfield Street. Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald has requested public opinion on the decision to close the shelter. His telephone number is 412 350-6500. To let Mayor Ed Gainey know what you think of the state of Downtown, call 412 255-2626.)