Venison: Pennsylvania’s Favorite Meat

The primary red meat of Pennsylvania is probably not at your local grocery store, but it may be romping through your backyard. And it turns out that venison (deer meat) trumps beef not only in popularity, but also, the experts say, in health benefit and nutrition.

Whether you find the deer in your yard to be a beautiful sight or the annoying creatures that munch your flowers, the fact is that these remarkable animals occupy a much more central place in Pennsylvania than most of us know. There’s a reason they were chosen to be the official state animal—they’ve been sustaining human life here since long before the arrival of European settlers.

In 2015, the Pennsylvania Game Commission sold 935,146 general hunting licenses to state residents. And last year, venison was introduced to fast-food restaurants when Arby’s began selling venison-steak sandwiches at 17 locations in popular hunting states, six of which were around Pittsburgh.

Arby’s wasn’t looking to promote the health benefits of venison, but to appeal to America’s 20 million hunters. “They hunt the meat, we have the meat,” said Luke DeRouen of Arby’s. “To walk the walk, we had to show them we had what it takes to bring a product to market.”

The Arby’s recipe begins with 5½-ounce venison steaks from the deer’s hind leg. The steak is marinated in garlic, cooked sous-vide—immersed in hot water and cooked slowly over time—and served on a bun with crispy onion strings and juniper berry sauce.

Venison is served in many ways: as steak, tenderloin, roast, sausage, jerky and minced meat. While leaner and richer than beef, it’s criticized by some as gamey. Nutritionally, however, venison beats beef again. Three ounces of venison has 134 calories and three grams of fat, while the same amount of beef has 247 calories and 15 grams of fat. Venison also contains high levels of iron, zinc, protein and amino acids.

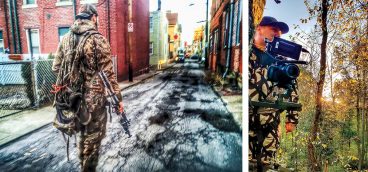

Still, venison is much less accessible. Selling home-processed meat is illegal, and in order to be sold in retail outlets, venison must receive USDA approval. As a result, most retail venison comes from New Zealand (as with Arby’s) or Tasmania and is more likely to be found in a specialty grocery store. So the most dependable source of venison in the U.S. may just be a hunting license and hours scouring the woods.

Today, deer often number more than 40 per square mile in Pennsylvania, and their numbers often raise the ire of suburban homeowners. But a little over a century ago, there was concern that deer were on the brink of extinction in many states including Pennsylvania. In response, Congress passed the Lacey Act, banning the selling or trading of animals, fish and plants obtained illegally. With that law and the decline of wolves and mountain lions, the state’s deer population soon rebounded, making overpopulation ultimately the chief concern.

Nonprofits such as Hunters Sharing the Harvest (HSH) help reduce the overpopulation while contributing venison to impoverished Pennsylvanians. Through HSH, hunters can take their tagged deer to one of 115 butchers to be processed for free—thanks to sponsors such as Applebee’s and Walmart—and delivered to a regional food bank distributor. From there, the meat is bagged and given to families in need or to soup kitchens.

“An average-sized deer, after it’s boned out and every drop of it is used correctly, could provide 200 meals,” said HSH executive director John Plowman. “And deer meat is really good: low fat, extremely high protein, low cholesterol. So it’s in high demand; there’s a tremendous amount of competition for deer meat.”

The venison is most easily distributed as ground meat, or “burger,” and every hunting season, HSH seeks to distribute about 100,000 pounds of processed venison to the state’s 20 regional food banks, which in turn re-distribute it to more than 4,000 local charities and ultimately to the 1.8 million Pennsylvanians who are considered to be food insecure.

Next week: What a Rack! The Story of Antlers