The remarkable story of Tom Vilsack began in a Pittsburgh orphanage where Dolly and Bud Vilsack adopted him. He grew up in Squirrel Hill and graduated from Shady Side Academy and later Hamilton College and Albany Law School.

In 1998, he upset a heavily favored Republican opponent to become the first Democratic governor of Iowa in 30 years. He heads the national Democratic Leadership Council, and now, at the end of his second and final term, Vilsack has announced his candidacy for presdient of the United States.

The 56-year-old Vilsack, however, doesn’t match the image of a glib, glad-hander one may expect. He’s a details-oriented policy expert, whose self-effacing nature can be seen in a rock that sits on a pile of autographs on his desk. When a visitor asks for his autograph, Vilsack instead shows them the rock, a piece of 9/11 debris brought back by Iowa National Guard volunteers, and the autographs he’s collected from police officers, firefighters, nurses and other social servants who, he says, are making Iowa a better place.

And though he’s been in Iowa for 30 years, there is a small room next to his office that offers a clue to his distant past — his Pittsburgh room, full of memorabilia from Pittsburgh’s sports teams. With a laugh, Vilsack recalled his visit last year to a Steelers-Vikings game in Minneapolis. He got a security escort down to the field and met the Vikings owner, who asked him how long he’d been a Vikings fan. Vilsack said he was actually a Steelers fan, effectively ending the brief conversation. He was then escorted to the Steelers sideline by security.

His accomplishments in economic development, healthcare, education and alternative fuels have led to impressive rankings for Iowa: 3rd lowest cost in doing business (Milken Inst. 2005), first in economic growth in economic growth in Midwest, 8th overall (U.S. Govt. 2005), first in per capita personal income growth (Morgan Quitno Press, 2006), first in average SAT scores (College Board 2005), lowest dropout rate (Kids Count, 2004), third most livable state (Morgan Quitno, 2006), first in ethanol, biodiesel and wind energy production (variety of sources, 2006).

Vilsack isn’t flashy. He’s been married to his wife, Christie, a teacher and former journalist, since college, and the two have sons Jess, 29 and Doug, 25. He’s neither a media star, nor the son of a president. He’s a serious guy from a small, Midwestern state of just under 3 million people. But he’s a guy who has gotten results. And, he’s a guy from Pittsburgh.

Q: Do you ever go back to your old

neighborhood?

A: Well, I was walking around there one day, and my wife Christie said “Why don’t you stop by your old house?” I said, “I can’t do that. It’s the middle of the day. People will wonder who the heck I am and think it’s kind of strange.” She said, “Oh go up there. Knock on the door.” So I got enough courage to knock on the door of 1300 Murray. This woman opens the door, and I said, “Excuse me, I’m Tom Vilsack,” and she looked at me and said, “Yes, and you’re the governor of Iowa. I’m so excited to meet you. I bought this home from your father.” I was totally shocked. She left and came back with a clipping from the Post-Gazette when I was elected.

I went to St. Philomena’s for first through fourth grades. The parishes got reconfigured so I ended up going to St. Paul’s Cathedral, fifth through eighth. My father graduated from Shady Side Academy and very much wanted me to go there. Not only to get a good education but to be challenged. And he was right. It was a great experience. My best friend, Doug Campbell, also went there. We had to go to summer school for remedial work in math and English to get in. I struggled academically the first year. My parents were separated at the time, because of my mom’s alcoholism. She was recovering and needed some time to get on her own two feet. My parents were reunited when I was a junior, and my grades skyrocketed.

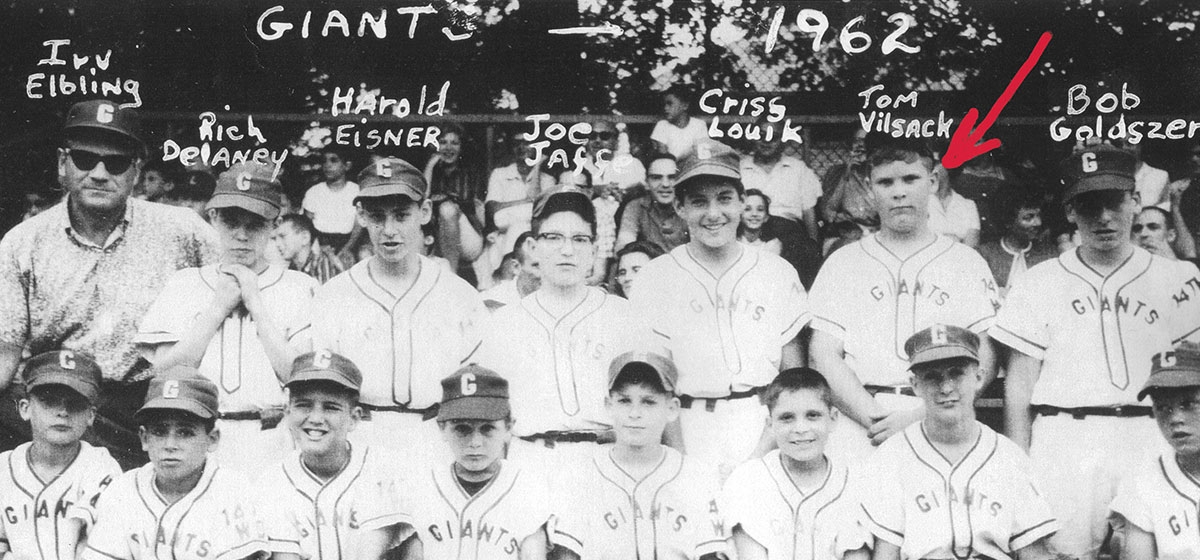

My parents started me in school when I was 5, so I was always physically a year behind. I wasn’t a particularly good athlete. I participated and played, but not very well. As a junior, I was playing junior varsity baseball, and one day the coach asked me, “What are your plans for next spring?” I was a poor-hitting, mediocre-fielding, right-handed first baseman, but I was hoping to make the varsity team. I said “Well I don’t know. Coach, what do you have in mind?” He said, “I’m looking for a good manager.” [Vilsack laughs.] So I managed the team. And I was a good manager. We played some of those games in early April, you know when it’s really cold? I’d build a little bonfire and heat up the bats so they’d be warm for the guys.

Q: Did you ever have an interest in

tracking down your natural parents?

A: I was taken out of a Catholic orphanage by my parents at a very young age. No, I really haven’t had that interest, because my parents did such a good job of making me proud that I was adopted. They gave me a special day – April 10 – is my adoption day. And they made it kind of special. And you never would have been able to tell any difference in how my parents treated my older sister who was born to them and how they treated me. All my family have passed away. My father died before I graduated from college, and my mom passed away just before our first son was born. My sister had a heart transplant at Temple, and then a year or so after that, she rejected the heart.

Q: How would you describe Iowa?

A: Iowa is a beautiful land of rolling hills, situated in the heartland between two rivers enormously important to the commerce of our country. Most people characterize it as agricultural, but we recently ranked second in the percentage of our economy that’s produced by manufacturing. We’re also a financial services and insurance state. We’re a people who genuinely believe in community. That’s one of the principal reasons we have the high quality of life, good schools and healthcare that we do. It’s a result of having 950 communities, 800 of which have less than 1,000 people — a series of small towns connected by one fundamental, overriding value. And that’s community.

Q: How did you get to Iowa?

A: I was 24 when I moved here. My wife’s from Mt. Pleasant, which is a small town of 8,700 people in southeast Iowa. When I graduated from law school, we had a choice of working in a law office in Somerset, Pa. We had decided we wanted a small town because of her background and my belief that I would do better in a small town setting as a young lawyer starting out. Christie’s dad sent us this wonderful, seven-page, hand-written letter on a yellow legal pad, espousing the virtues of Mt. Pleasant. He was a lawyer and doing pretty well with a practice in Mt. Pleasant. He offered me a position at $1,000 a month. And so we moved to Iowa.

Because I wasn’t a very good athlete, I was still very interested in being connected in some way positively with sports. There was a bond issue for a sports facility for youngsters that had failed. And I came home one day, aged 27, and said “I’m going to raise the dreaming that some day, you, too, could play — bouncing a rubber ball off a brick wall, making fantastic catches in your back yard that no one else could see but you.

When your team goes up against what is considered to be one of the greatest baseball teams of all time and wins dramatically in the 9th inning of the 7th game with a home run — you grow up thinking that the impossible is indeed possible. And if there was one lesson that the city of Pittsburgh taught me when I was growing up, it was that. Not only was it sports teams, but it was also the Renaissance that was taking place when I was a youngster, changing it from a dirty, gloomy place to a place of vibrancy and activity. I’ve always been proud of my Pittsburgh roots.

Q: How did you get involved in politics?

A: It’s sort of a unique circumstance. Our mayor in Mt. Pleasant, who had been mayor for quite some time, was actually shot and killed in a council meeting by a citizen who was upset over a sewer problem. He killed the mayor and seriously wounded two members of council. The mayor’s father asked me if I would consider running for mayor. I’d been involved in community activities, but I really hadn’t thought about running. Joe Biden was running for President back in 1986, and Christie and I were involved in his campaign. He quoted a Greek philosopher who apparently said that the penalty for not getting involved is that people less qualified end up governing you. And so it made me think running for mayor could be an interesting experience for myself and my kids. They were convinced that I would get hurt, and I didn’t want them to think that you’d get hurt getting involved in politics. I was mayor for two terms. I didn’t run for a third term. Nobody ran, and I was the write-in candidate who got the most votes so I ended up being elected to a third term. Midway through my third term, I ran for the state senate. I was elected in a three-way race.

Q: Have you been a Democrat philosophically your whole life?

A: My mother was a staunch Republican, and my dad was a Democrat. And growing up in a Catholic family in the late ’50s and early ’60s, you were enamored with the Kennedys. That made a big impression on me. And then after John Kennedy was assassinated, my leanings would always be Democratic.

Q: Do you think the country’s in need of a Renaissance?

A: What’s happening in America today is that our national leaders are encouraging us to be concerned only about our little niche. We’re a more inspiring and optimistic country when we look at rising to some challenge that no one thought was possible. And then besting that challenge. Whether it’s putting a man on the moon or, in my case, building an athletic facility that nobody thought was possible. Accepting those challenges is what has always made this country great. What’s missing from the national dialogue is a call to common purpose, to service. It may be as simple as driving a flexible fuel vehicle car. Or deciding that you’re going to be a healthier person so you don’t contribute to rising healthcare costs. Our daily lives are not being connected to a national purpose.

When I was growing up, there was the President’s Fitness Council. We didn’t know there was no direct connection between that and putting a man on the moon. But we thought there was something that we could do to help our country by being physically fit. And by picking up litter. We thought we were helping society, and we reminded our parents not to throw stuff out the window. There isn’t that kind of call today.

There’s so much discussion of the threats from the outside. There’s not enough recognition that we’ve got to strengthen America from the inside. So that we can, indeed, meet the threats from the outside more effectively. We can’t ignore budget deficits, healthcare costs and the fact that we’re dependent on foreign oil. The reality is the solution to all those problems is in the hearts of every single American. The tragedy of 9/11, in addition to the 3,000 lives that were lost, is that we weren’t called. It was an enormous opportunity. We had a unified world, much less a unified country. We didn’t take the lead internationally, and we didn’t ask anything of our citizens.

Q: Whom do you admire?

A: I have great admiration for my mother for her tenacity, strength and will in her battles to overcome her addiction. She literally made herself into an independent, strong woman. She didn’t learn to drive until her late 40s after she conquered her addiction. She hadn’t been employed outside the home but got a job at Mellon Bank and got several promotions. She lost her husband shortly after they got back together again, and when he died, there was just enough money to pay for the funeral bill. I admire my father because he understood people and really liked people. He valued education above everything else. Because of that, he gave me opportunity — sacrificing a lot financially. He literally sold memberships to the Pittsburgh Athletic Association to send me to Shady Side and college.

Legally, I have an extraordinary amount of respect for my father-in-law who was a tremendous human being. Politically, I’ve always been moved by the words of Robert Kennedy and his belief in the ability of people to make a difference.

The other person I have profound respect for and owe a great deal to is Christie, my wife. I was sort of like a wilted flower before I met her, And she was sort of the fertilizer and the water. She really fundamentally changed me as a person and created opportunities far beyond what I ever thought was possible. When you grow up in a circumstance as I did, when your mother is a heavy drinker and hospitalized a number of times — mental hospitals — it’s not quite the kind of thing where you can invite everybody over on the spur of the moment. You never knew whether she was going to be drunk or not. And if she was drunk, she was pretty ugly. There were times when things got pretty tough. So because I went to school with kids not from my neighborhood, in some ways I was always on the fringe socially, on the outside. When I went to Shady Side, the same thing happened. I didn’t know any of those people who’d gone through the junior school and the middle school. Doug Campbell and I kind of stuck together. In college, I was a freshman adviser, so I wasn’t with my fraternity brothers because I had to work my way through college. I needed somebody to tell me it was OK to have a good time, to laugh and spend a few minutes with friends. That wasn’t easy for me. Christie made a huge difference. If she walked in here and you met her, you wouldn’t want to talk to me anymore. You’d say “Well he’s OK, but boy she’s terrific.” She’s really interesting and alive and enthusiastic.

Q: What goes into the calculus of deciding to run for president?

A: There are a lot of nuts and bolts things that people who advise you have to think about. I think you have to decide for yourself whether or not you could do the job. And whether you’re the best-suited person for the time to do the job. And whether you’re willing to make the sacrifice that it would take, of personal and family time and energy. On the one hand you say, this is pretty interesting that we can even have this discussion and have people actually take it seriously. On the other hand, it’s such an enormous undertaking. So you look at this decision with a mixture of excitement and fear.

Q: Is it a good or bad thing that you weren’t John Kerry’s running mate?

A: In this business you have to have confidence in your abilities, and I like to think I could have helped John Kerry. It was interesting, because when the discussion first began, I’m not sure people took it very seriously. But as it progressed, it got more and more serious. The weekend that he made the decision, he had three names: Edwards, Gephardt and Vilsack, and he had to choose. That’s pretty heady company. It helped to raise my national profile a little bit, so in that respect it’s been beneficial.

Q: How do you go about building a campaign apparatus on a national level?

A: When I first ran for governor, my thought process, being a lawyer, was that “This is like a case, where I have to persuade the public.” The more I got into it, I realized that’s not the right metaphor. It’s really like a small business. And I’m the product. And I need people to sell me. I need people to invest in me to build the product and brand and market the product. So I need to basically establish a small business. The campaign manager is the CEO or the COO. And the person in charge of raising the money is your CFO. When you’re the underdog, and you’re not as well known, it’s a little more difficult ficult finding these people. Because you have to find people who want to make a winner, not be with a winner. You start with the most knowledgeable people. You have to trust folks who know people who know people to give you advice about whom to talk to.

Q: Even if you’re not the front runner, are you almost obliged to run if you have a chance of winning?

A: I think if you approach it as a duty, you’re not going to be able to do it well. I think you ought to approach it with: Does the country need what I think I can provide? Can I make a difference if I participate? There are 300 million Americans and only one person gets elected President, so the odds against anyone are huge. So you have to ask yourself: At the end of all of this, if you’re not successful, will you have made a difference in the process, debate, policies and focus of the country? If you think you can make a difference, then you may be inclined to do it.

Q: What can you provide?

A: I understand Main Street. A lot of politicians talk about Main Street. My address is 402 N. Main, Mt. Pleasant Iowa. And I understand the potential greatness of those who live on main streets around the country. I believe that, knowing that, I can encourage people to look within for the solutions to this country’s biggest challenges. And I think that if we do that, we’ll make America much stronger and much safer. I also think that we’ll be able to look at our children and tell them that we kept faith with the American experience and the American bargain — that each generation is supposed to do whatever it takes so that the next generation will find an America that’s better, stronger, more hopeful, more optimistic and with more opportunity. That’s hanging in the balance right now.