Three Pittsburgh Poets, Three Distinct Voices

Poetry can mean different things to different people. For some, it’s celebrating the glorious music found in the end-rhymes of Robert Frost. For others, it’s a love of language poetry or blunt confessionalism. For Pittsburgh’s Sam Hazo, former Poet Laureate of Pennsylvania, it’s the “visionary” poetry of T.S. Eliot and Seamus Heaney. Hazo, in his recent book of essays on poetry and public speech, The Power of Less (Franciscan University Press), claims that true poetry, to him, attempts to satiate “our hunger for universal feelings precisely addressed.” I think he’s on to something, as the world of poetry is full of unique voices and contrasting styles that satisfy an array of aesthetics.

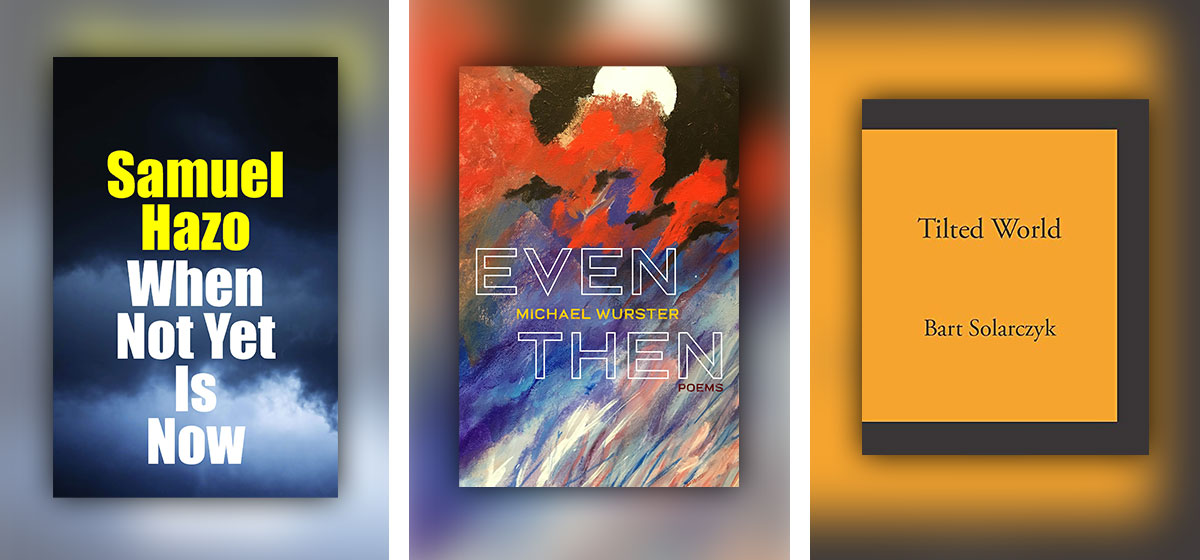

Cribbed from his mother’s old notebook, there’s a line in the poem “Lost Son Found,” from Hazo’s other recent release, the collection When Not Yet Is Now (Franciscan University Press) that reads, “‘Imagination / is love with poetic fervor / and peculiarly private as it is / sacred.’” The verse struck me as not only poignant, but a summation of tone to be found in recent collections by a trio of Pittsburgh poets, including Hazo, Michael Wurster and Bart Solarcyzk.

With decades spent teaching and guiding others in workshops, as well as a list of accomplishments and publications as long as my arm, their books prove worthy of a closer look.

When Not Yet Is Now is Hazo’s 30th collection of poetry, a remarkable writing accomplishment that showcases the nonagenarian as sharp as ever. The professor emeritus at Duquesne University, as well as founder and director of the International Poetry Forum, highlights a need for the tangible in “The World We’re Here to Make.” There, he writes, “My body’s eyes are fingertips. / They let me see whatever / I touch: a waxed tabletop, / an apple in my palm expecting / to be bitten, my wife’s eyelids / parting when I kissed her awake.” The synesthesia of the lines here is reminiscent of W.C. Williams influential line, “no ideas but in things.”

In “Unbudgably Yours,” Hazo reminds readers of the satisfaction that comes with seasonal weather where “trees are slumbering in place. / that grass stays hidden under lawns / of snow, that roots and bulbs / await a warmer reveille… / when I can / waken to enjoy the pleasure / I deserve for earning April.” Even in the midst of a mild winter (so far) there’s a satisfaction in the straightforwardness of the image. Hazo can be, at times, a bit curmudgeonly about modern times but the collection abounds in the insightfully reflective tone he’s best known for as in poems like “A Tale of Two Ankles” and “In Troth.” In a favorite, “A Loner Breaks His Silence,” Hazo writes, “The curse / of brevity defines each life / as tragically mortal. / The same / is true of beauty. / Jasmine, / asphodel, and orchids bloom / their way to rot.” It’s beautifully existential and emblematic of what’s to be enjoyed in When Not Yet Is Now.

Michael Wurster, a stalwart of Pittsburgh’s vibrant poetry scene, has helped hundreds of budding writers find their voices as both a founder of the Pittsburgh Poetry Exchange and teacher at Pittsburgh Center for the Arts School. His latest book (and his first published by the highly regarded University of Pittsburgh Press), Even Then, finds him championing a somewhat minimalist approach mixed with a sly sense of humor. A nice example is “His Young Days,” which reads, “There was no / air conditioning / in Texas then. // They would / drive around / in cars / with the windows open, // shooting at things / keeping cool.” The starkness of the imagery here dovetailing with an unknown speaker creates a poetics that is more a delicious bite than a banquet.

Though some of the poems in Even Then are stripped down affairs, others point to idiosyncratic moments of childhood memory. One such moment plays out in “The Yellowjackets,” where Wurster writes of “Flaming smoking rags / at the end of stick / down their hole. / It was an experiment. // They came out the other end. // Four inside my shirt / stinging stinging stinging / as I ran toward the house.” It’s a visceral scene that left me smiling even as I typed it. Another, “Early Morning, Looking Out,” reads in full: “I thought it was snowing, / but it was only // the ashes from the crematorium.” The brevity here is reminiscent of work by Charles Simic, who gets name-checked elsewhere in the collection.

While too much brevity might leave readers without a foothold in his speaker’s world, Wurster smartly adds more detail in some longer poems like “The Hotel Earle” and “The War,” the latter reading like a list of childlike observations, including “ceilings are as high / as the halls of heaven… // a black dining car porter / with a shiny bald head, / wire-rim spectacles, / a big smile / and a courtly manner… // the toilet tank / is attached to the wall / above the toilet, / to flush it / you pull on a chain…” The poem culminates with the mention of the boy’s father being visited at “a place called St. Elizabeth’s // where another man / named Ezra Pound / walks the grounds / in the morning / in his bathrobe / talking to himself.” It’s a neat piece of connection that leaves the speaker less than six-degrees removed from the father of poetic Modernism.

The effectiveness of Wurster’s concise approach in Even Then showcases the maturity of a writer who has clearly found his voice. Not to be outdone in the brevity department is the first full-length collection by Ross Township’s Bart Solarcyzk, Tilted World, just released by Kristofer Collin’s local Low Ghost Press. With nine chapbooks to his name, Solarcyzk’s poetry calls to mind the blunt honesty of Charles Bukowski while embracing, in places, the barebones description found in haiku. One example, “Li Po,” written after the short-form master, reads, “A hat full / of wine / by the river // my face // the moon / in my hand.” It’s a clever mash-up of styles.

While Solarcyzk may be something less than Hazo’s “visionary” poet, it’s obvious he has a lot of fun with it. In “Waking Up with Jesus,” he writes, “After three days / we both rise // he was dead // I was just / dead drunk.” Embracing Eliot’s “objective correlative, “She’s Packed,” reads, “& off to college / forgetting the big fuzzy hat / that smells like her hair.” In another, “Dirty Old Poet,” finds the speaker, “Flirting with the waitress / as she feeds me cold Coronas // she folds her tips / her fingers taste like lime.” If anything, Tilted World will remind readers that poetry need not be stuffy but can be a place where misfits and mavericks can find a home.