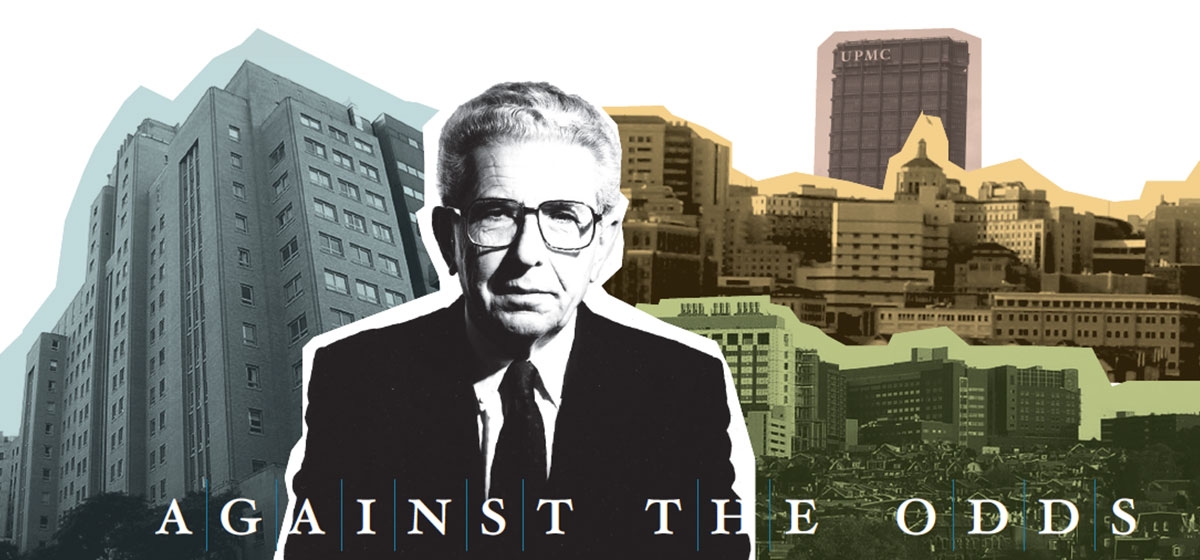

Against All Odds

Until the spring of 1944, Hungary’s pre-war population of 700,000 Jews remained largely unscathed. Hungarian Regent Nicholas Horthy had resisted Hitler’s calls for the deportation of Hungarian Jews into the killing maw at Auschwitz/Birkenau, 175 miles north of Budapest.

Then, on March 19, 1944 Hitler ordered the Wehrmacht to occupy Hungary. By July, 437,000 Hungarian Jews had been deported to Auschwitz and certain death.The SS continued rounding up Jews until the Red army captured Budapest in February 1945.

One such roundup occurred Nov. 13, 1944. In one line were those with a Schutz-Pass, a document issued by Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg that placed bearers under the tenuous protection of the Swedish government. In a second line were those marked for deportation and death. Among them was 20-year-old Tamás Feldmeier. Machine-gun-toting Hungarian fascists marshaled the helpless Jews. For an hour, young Tamás watched the half-dozen guards. Sometimes six pairs of eyes were on him, sometimes three. Like a safecracker listening to tumblers falling into place, it was two, then one and, for a split second, none. Instantly, he took four steps to the Schutz-Pass line and reprieve from death.

Tamás Feldmeier, who would later become Thomas (Tom) Detre, was born in Budapest, the only child of Geza and Gabriella Feldmeier. His father was a German-trained obstetrician-gynecologist. The Feldmeier household was an intellectual hothouse; they seldom dined alone. Through a succession of Austrian and German fräuleins (governesses), Tom’s first language was German. He was precocious in several dimensions; he began to smoke at age 12 and, after reading several books on Sigmund Freud, decided to become a psychiatrist at age 14. “My father was upset,” he would say later. “He wanted me to be a ‘decent doctor,’ not a psychiatrist.”

Early in the war, Tom became convinced that his parents must leave Hungary. His father thought otherwise. A decorated officer in the Hungarian Hussars in the First World War, he thought he would be excepted. He was wrong. He and his wife and 20 relatives were murdered at Auschwitz.

Soon after the Russian liberation in 1945, Tom enrolled at the Pázmány Peter University of Science in Budapest. Like many other Holocaust survivors, he altered his surname, exchanging Feldmeier for Detre. In French, the verb etre means “to be” and for Tom Detre, the new name signified his intention to continue “to be”—to live and to thrive.

While it was Freud who gave Detre the impetus to pursue psychiatry, he soon turned against psychoanalysis. He reasoned that, if the disease is neurologically/biologically based, no amount of talking will effect a cure. And in those limited cases where analysis may have positive outcomes, it is prohibitively expensive. In 1946, at the age of 22, Detre believed that the future of psychiatry lay in psychopharmacology—the treatment of mental disease through drugs. Detre distinguished himself academically while taking increasingly responsible positions at the state mental hospital, including acting director for six months at the age of 23. In that capacity, he was ordered by a Communist Party official to put on his white coat and march in a May Day workers’ parade. His answer was less than politic: “If all the crazies are outside marching, who will take care of the crazies inside?” He promptly received an invitation (no refusals accepted) to the Communist Party’s secret police headquarters. Detre never lacked for luck; the hearing officer turned out to be a former lover who said, “Darling, this is not the place for you. You have too big a mouth. Make every effort to get out.”

The May Day incident wasn’t isolated. Having narrowly escaped the Nazis, he set his sights on breaching the Iron Curtain. A cousin who was a friend of the Italian ambassador advised Detre that if he could get an appointment at an Italian university, he would arrange for a visa. Detre had recently written a provocative paper on electroshock therapy and sent it to the noted Italian neurologist Ugo Cerletti, the co-inventor of electroconvulsive therapy. The invitation was forthcoming, and Detre was off to Rome.

He was in Italy from 1947 to 1953, completing his education while working at the Italian National Research Council. At the same time he developed a lucrative private practice. The Italian years were good ones, he would say. “You’ve probably seen the movie ‘La Dolce Vita.’ That was the period I lived in Rome. I had a good time!” In other words, the legendary Detre charm, which was later employed with telling effect on Pittsburgh’s power brokers, got an early trial run with a bevy of Italian women.

Crossing the ocean

Detre made it to the U.S. in 1953, working in hospitals in New York City and then at Yale University. In 1956 he married Katherine Maria Drechsler, like himself a Hungarian Jewish refugee. Dr. Katherine Detre would become one of the nation’s foremost epidemiologists. Theirs was a 50-year marriage and romance, lasting until her death in 2006.

Despite the dominant psychoanalytical orientation of the Yale Department of Psychiatry, Detre began to prescribe treatments with anti-psychotic drugs introduced in the early 1950s, coupled with non-psychoanalytic psychotherapy. In 1960 he formed Tompkins I, an experimental psychiatric unit at Yale-New Haven Hospital. The premise was to prescribe short-term treatment to acutely ill psychotic patients. Long-term care would then be provided on an outpatient basis. Detre viewed institutionalization of the mentally ill as expensive, ineffective and occasionally cruel. In the next 20 years, this de-institutionalization of the mentally ill would become part of the canon of psychiatry. The third element of Detre’s pioneering approach was research. He believed that research and clinical care must not only exist side by side, they must be integrated.

By 1972, Detre was at the top of his field. He was psychiatrist-in-chief at the Yale-New Haven Hospital and a tenured full professor. He had co-authored the influential and controversial 733-page “Modern Psychiatric Treatment.” “It was the first book to systematically review all potential psychiatric drug treatments and the understanding of the physiological bases of mental illness,” said Dr. Loren Roth, former senior vice president for quality care and chief medical officer at UPMC. Detre was just relieved to have gotten his professorship prior to publication, fearing that the book’s tone was “so provocative they [would] kill me for it.” His work would eventually change psychiatry at Yale, but psychoanalytic headwinds would make it slow going. He was ready for a new challenge.

Arriving in Pittsburgh

The University of Pittsburgh had two strikes against it when recruiting top-caliber talent such as Detre. First, it was in Pittsburgh. Though the skies had been cleared by 1950, perceptions lingered of smoke, smog and a pitch-black sky at 9 a.m. Second, as an academic medical center, the university was a laggard. Despite having a rich heritage in banner names such as child development authority Dr. Benjamin Spock and polio conqueror Dr. Jonas Salk, both had departed. Pitt ranked a lowly 37th in NIH funding.

The state-owned Western State Psychiatric Hospital had opened its doors in 1942, and in 1949, the commonwealth effectively transferred ownership of the renamed Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic (WPIC) to the university. WPIC was an academic hospital in name only. The psychiatry department as well was an also-ran; most of the faculty were private physicians. State officials regarded WPIC management as arrogant, and state funding was in jeopardy. As the state threatened to cut funding, top administrators sought to make WPIC more responsive to the state and to strengthen biological psychiatry. They successfully appealed to the R.K. Mellon Charitable Trusts for a $5 million grant to attract a transformative chairman for the department of psychiatry.

Detre thought the situation required radical change. He wrote a four-page, single-spaced letter outlining his plan and his demands, “I’m too vain to go down the drain. If you want me to do something you have to provide the resources.” In March of 1973, Detre became chairman of the department of psychiatry.

Making money flow

No sooner had Detre walked in the door than the state cut WPIC’s appropriation from $2.5 million to $1.2 million. Detre went to Harrisburg. He didn’t ask for anything, only how he could help. His parting words were: “If you get sick, come to us. Here’s my number. If you forget it, I’m in the telephone book.” His charm worked, and appropriations rose to $3 million.

Detre was arguably the most important recruit in the university’s 200-year history. His vision of a leading department of psychiatry rested upon great clinicians and researchers. Building a preeminent department or university is at best tortuous. First, you have to seed your scholars with an occasional star. These A-level scholars then attract more and finally predominate over the diminishing number of less talented scholars. But before you recruit you have to have money—lots of it—and in 1973 the cupboards were bare.

Along with state funding, the two revenue streams flowing into WPIC were clinical income and research grants. Detre enhanced clinical revenues with two changes. The portion of the clinical income that had previously been returned to the school of medicine would remain in the department of psychiatry. As current UPMC president and CEO Jeffrey Romoff tells it, “Our ability to keep that clinical money was a turning point in our history because it provided the resources to pursue academic and clinical excellence.” Soon after, Detre imposed a 20 percent tax on all clinical income. At first blush, this might seem to be a zero-sum game, more for the department and less for the doctors. But it didn’t work out that way for two reasons. As great researchers and clinicians came into the department, they attracted more patients, giving them more clinical revenues. The revenue pie was further increased by reimbursement optimization. George Huber, formerly with Blue Cross, understood every nuance of the complex subject of reimbursement: “We employed every legal reimbursement optimization strategy we could,” he said. It became a win/win for the clinicians and for the department.

On the research side, indirect costs (overhead) were also retained in the department. As more outstanding researchers came into the department, research grants increased, making more funds available for further recruiting. These changes created a self-funding mechanism that also integrated patient care, research and education.

Detre’s recruiting record looks a little like Ty Cobb’s batting average. Beyond doubt, his best recruit in a galaxy of stars was Jeffrey Romoff. Talking about Romoff as the trailing spouse stretches the truth a little bit, but Detre’s initial interest focused on Romoff’s then-wife Vivian, who was the chief psychiatric nurse at Yale-New Haven Hospital. Romoff, 27, was working for a small mental-health counseling group in Connecticut. He sent Detre a plan he had written for a community health center seeking a federal grant. “I read it and decided he was a very bright man,” Detre said. “And I knew exactly what I wanted to do with him after I talked to him.”

In 1973, Romoff was hired to head up the newly created Office of Education and Regional Programming. The mandate was to provide consulting services for mental health providers throughout western Pennsylvania. The mental health providers would receive expertise they could get nowhere else, and the project won great plaudits from the commonwealth. Two years later, Romoff was named executive director and Detre’s right-hand man at WPIC; he was on his way.

During the transformation of WPIC, there were potholes all along the way. Detre was shocked by the work habits of the part-time faculty. They ambled in about 9:30 a.m., had a leisurely coffee break, then lunch. After lunch, Detre recalled, “You couldn’t find a gin rummy partner, let alone four for a bridge game.” Soon all that changed.Detre once again had to confront his old bugaboo, the psychoanalysts. He insisted they do clinical research on the value of their services; they refused. He invited them to appoint a director with a strong research background. Again they refused, and took their dispute public in an attempt to discredit Detre and embarrass the university. They partially succeeded, but with strong backing from Dr. F. Sargent Cheever, vice chancellor of the Schools of the Health Professions, and Pitt Chancellor Wesley Posvar, Detre prevailed. In 1976, the Psychoanalytic Institute withdrew from the university.

From 1973 to 1983, the money came in and the talent followed. In 1977, WPIC was given the prestigious designation of Clinical Research Center for Affective Disorders by the National Institute of Mental Health. NIH research grants increased from $450,000 in 1973 to $9.5 million in 1983. NIH grants constitute the gold standard of competitive validation, and in 1983, WPIC rose to third in the nation. Full-time faculty increased more than fourfold, from 36 to 150.

By 1982, Detre had reached a crossroads. His national reputation was attracting impressive job offers, including chair of psychiatry at Columbia University. In his 10 years at WPIC, he had battled stiff headwinds all the way. If he moved to another department of psychiatry, trumpets would herald his arrival. It was a siren song of no little appeal. Posvar knew he had a leader of inestimable value in Detre. Pitt’s Senior Vice Chancellor for Health Science, Nathan Stark, stepped into the breach. He shared Posvar’s opinion of Detre’s value to the university’s future. Stark was ready to retire in a year, and he and Posvar cleared the path for Detre to succeed Stark. It was an offer Detre couldn’t refuse.

Since his arrival in Pittsburgh, Detre had pushed to erase the walls between academic disciplines and foster collaboration, saying, “The Lone Ranger has died.” Funded by a $1 million grant from the Benedum Foundation, he established a clinical and research program in geriatric medicine that has gone on to secure $200 million in funding, making it the largest in the country.

Detre fixed on cancer treatment and research as a centerpiece of this interdisciplinary collaboration. He spread the net wide. Relations between Posvar and Carnegie Mellon University President Dick Cyert perennially hovered between cool and frigid. Detre went to work on Cyert, however, and CMU was soon in for a host of collaborations, including the Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (PCI).

The Cancer Institute

For PCI, Detre tapped two distinguished university clinical researchers, Drs. Bernard Fisher and Gerald Levey, to lead the planning committee with Romoff’s assistance. The center would transcend all jurisdictions, assuring equal access for all hospitals, schools and departments of Pitt and CMU. Most important, the plan again permitted Detre to “tax” clinical revenues of the participating hospitals, assuring a steady flow of funds to undergird the campaign to attract the nation’s best oncology researchers.

The Richard King Mellon Foundation stepped to the plate, making an initial contribution of $3 million, another $3 million in 1986, and a thumping $8 million in 1989.

The search committee’s first candidate to head PCI was a specialist in chemotherapy. Detre, however, gave him a thumbs down, likening chemotherapy to the half-blind cartoon character Mr. Magoo, trying to swat flies with a submachine gun. Chemotherapy had its place, he felt, but didn’t represent the future of cancer treatment. PCI chose instead an internationally recognized tumor immunologist from the National Cancer Institute, Dr. Ronald Herberman. From 1985 until his retirement earlier this year, Herberman built PCI into the nation’s largest cancer center, home to more than 300 cancer-related faculty. PCI is one of 60 interdisciplinary collaborations begun during the Detre years, including the AIDS Research Center, Biomedical Informatics Center¸ the Tissue Engineering Initiative, and the Women’s Heart Center.

Creating UPMC

Upon becoming senior vice president for the health sciences in 1984, Detre immediately named Jeffrey Romoff associate vice president. UPMC was on the horizon. The virtuous cycle of medical research, education and unsurpassed patient care behind the WPIC success story was now to be applied again, not just to another department, hospital or even a school. The vision of the Detre team—with Romoff, CFO John Paul, George Huber and Loren Roth among others—was applied across the spectrum, to all the departments, all the schools, and eventually all the hospitals. It had taken 20 years to transform WPIC. In less than half that time, the architecture and mechanics for the transformation of the entire health system would be in place.

At that time, the leading hospital in Pittsburgh was the tightly unified and aggressively managed Allegheny General on Pittsburgh’s North Side.

By contrast, the University Health Center of Pittsburgh was a loose grouping of independent teaching hospitals, including Presbyterian University, Eye & Ear, Montefiore, Veterans’, Children’s, Magee- Womens, WPIC and Falk Clinic. The hospitals, their boards and administrations, guarded their independence, but the geography was favorable for synergies. With the exception of Magee-Womens a few blocks away, all the other hospitals were set cheek-by-jowl on Pitt’s upper campus. And while they were academic non-starters and under- managed, they were money makers with total revenues exceeding $400 million.

Not all the blame rested on the hospitals. The university’s School of Medicine paid the salaries of full-time faculty but received little return in the way of medical research and education. Past leadership had lacked either the vision or the intestinal fortitude to demand the kind of monetary support that was rightfully theirs.

How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time. Falk Clinic, the outpatient clinic for patients from the university-affiliated hospitals, was the first bite. It was a ripe apple ready to fall. The university’s committee on the health sciences, chaired by Farrell Rubenstein, became the board at Falk and then brought it under the management of the Detre team. It dovetailed nicely into the PCI initiative. As Falk provided outpatient care for PCI patients, Detre’s “tax base” grew, providing additional research funding.

For Detre and his team, Presbyterian University Hospital was the “great white whale.” But a frontal Captain Ahab assault (doubtless with Romoff throwing the harpoon) was not the way to go. Eye & Ear Hospital was the key by which to unlock the Golconda treasure at Presbyterian. Eye & Ear occupied 180 beds in the west wing of Presbyterian, but with the growth of outpatient surgery, those beds were largely vacant.

When Dr. Tom Starzl was recruited, his revolutionary liver transplant program made Presbyterian the transplant capital of the world. The hospital desperately needed those largely unoccupied Eye & Ear beds. The logical move was for Presbyterian to take over Eye & Ear. Negotiations were under way, and it almost happened. Unfortunately for Presbyterian, but fortunately for the future of UPMC, the 800-pound gorilla pressed the smaller Eye & Ear too hard. The little guys turned down Presbyterian’s offer. J. Wray Connolly, a top H.J. Heinz executive who chaired the Eye & Ear board, called Detre and suggested that Pitt, rather than Presbyterian, should take over Eye & Ear.

For Detre and Romoff, the opportunity was like manna from heaven. With Presbyterian salivating for those 180 vacant beds, Eye & Ear was a strategic prize. But there were wrinkles to work out. Presbyterian chair George Taber, their great Mellon benefactor, wasn’t happy about the Eye & Ear cup being dashed from his lips. But he knew that the Presbyterian board and administration had to share a good measure of the blame. Second, Detre had to convince a risk-averse Pitt administration, in particular Chief Business Officer Jack Freeman, to accept the prize that had been offered. The price was a $10 million funding of the Eye & Ear Foundation. The money was eventually generated by efficiencies that the WPIC team brought to Eye & Ear. And grants from the new Eye & Ear Foundation went to support the academic medical mission. The Eye & Ear key was now firmly in the Presbyterian lock.Founded in 1893, Presbyterian opened its dominating edifice on Pitt’s upper campus in 1938. It was a great building, but not a great hospital. Presbyterian made no pretense of being an academic hospital; it was a self-proclaimed community hospital. Presbyterian administration sought to curry favor with Blue Cross, the insurance intermediary for Medicare, by keeping its reimbursement claims for Pitt’s residency programs to a bare minimum. This ill-conceived “revenue minimization strategy” still left the hospital a solid earner, but effectively killed any serious research effort at the university.

The Presbyterian board was comfortable with their stewardship of a financially solid, non-academic, teaching hospital. But Detre and Romoff knew from their WPIC experience that with the trinity of superb patient care, education and research, the hospital as well as the medical school could become institutions of national distinction. Deep in their bones they knew this would happen. The Presbyterian board did not share this vision because they didn’t understand it. Huber had an idea: “Let’s educate the board.” So Detre, Romoff and Huber interviewed all 29 members of the Presbyterian board, and step by step the board bought into the vision of a great academic medical center.

As he did for Eye & Ear, Huber transformed the vision into a working agreement. Romoff termed the 1986 concept paper “the Magna Carta of UPMC.” It established the Medical and Healthcare Division of the University of Pittsburgh (MHCD, later UPMC), headed by Detre with Romoff as executive vice president. It included WPIC, Falk Clinic, Presbyterian, Eye & Ear and the School of Medicine. Within 20 years, the WPIC model would drive UPMC to national and international distinction.

Winding down

Katherine Detre constantly badgered her husband about his smoking. “Only you and the truck drivers still smoke,” she told him. Detre, however, continued to puff away with an ebony cigarette holder at a three-pack-a-day rate. A heart attack in 1992 ended his smoking and altered his career. Romoff assumed responsibility for UPMC, and Detre remained as the university’s senior vice chancellor for the health sciences. He finally stepped down in 1998 and Dr. Arthur Levine, a top director at the National Institute of Health, was recruited as senior vice chancellor for the health Sciences and dean of the School of medicine.

The results speak for themselves. For the fiscal year ending June 30, 2008, system-wide revenues for UPMC were $7.1 billion. UPMC has 20 hospitals in Western Pennsylvania and expanding international operations in Italy, Ireland, the U.K. and Qatar. As of December 2008, the UPMC Health Plan insured 1.3 million lives, and UPMC has become an integrated global health enterprise and one of the leading nonprofit health systems in the nation.

Hand-in-hand with the rise of UPMC go Detre’s transformation of the health sciences at the University of Pittsburgh. At the time of Detre’s arrival, the university ranked 37th in NIH funding; when he stepped down in 1998 it stood 10th. In fiscal 2007, the health sciences received NIH grants of $457 million, making the university the 6th largest recipient of NIH research funding. Detre allows as how the move from 10th to 6th may have been more difficult than the long climb from 37th to 10th.

Dateline Pittsburgh—Jan. 14, 2009: “Pitt scientists make key diabetes finding. A team led by Dr. Andrew F. Stewart, chief of the university’s division of endocrinology and metabolism, has identified key molecules…” When you see articles such as these in local and national papers—there have been hundreds in the past and there will be hundreds in the future—think of Tom Detre. They are ongoing testimony to his enduring contributions to our region’s mental, physical and economic well-being.

The soon-to-be-released “Beyond the Bounds: A History of UPMC” by Mary Brignano aided the research of this report.