Friends in Unfriendly Times

Adena Johnson Davis remembers marching up to the front desk at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Nursing, plunking down her test scores, report cards and transcripts. She was a slight, young woman and had been an ‘A’ student at Peabody High School.

For sure, she thought, this will get me in. The school’s secretary, a pretty white woman with a lilting Southern accent, gave it to her straight: the school was not accepting blacks.

This was 1942.

That same year, a slender, self-assured young woman, co-valedictorian at Westinghouse High, went to every nursing school in the city. Presbyterian, St. Francis, Allegheny General and Passavant hospitals. They all said the same thing. Whites only.

“I was absolutely livid because I was told it many times and went to many schools,” remembers Rachel Poole, who later became the first black director of nursing at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. “After a while it got to be old hat though, and I said to myself, ‘Just wait. I will so get in.’”

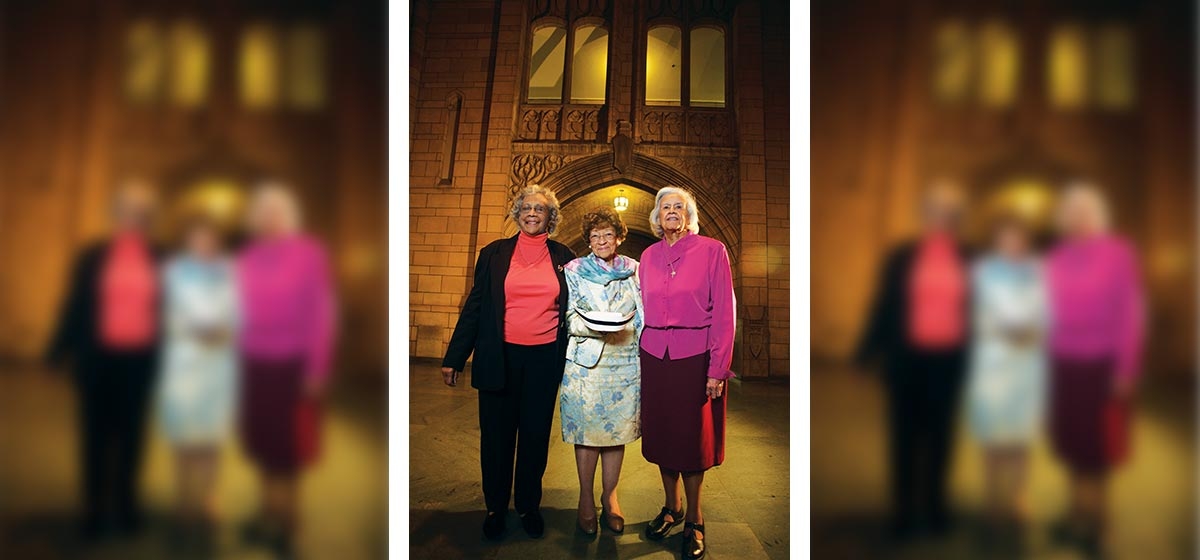

A year later, both women got in. Along with Poole’s childhood friend Nadine Frye, they broke the nursing school’s color barrier. This year marks the 60th anniversary of their graduation, the first black students to earn nursing pins from the University of Pittsburgh. When they donned the pins for the first time, another brick in the wall of racial segregation had fallen.

Not that the world changed overnight. They still couldn’t eat in white restaurants, swim in white swimming pools or try on hats in white department stores.

The women — all 83, all living in Pittsburgh — were part of a generation of “firsts” —blacks who broke the color barrier in dozens of institutions.

Life for black college students at white schools such as Pitt in the 1940s could be isolating and full of trials, says Consuella Lewis, an assistant professor of education at Pitt. “They had to have a very positive sense of self esteem because of what they faced day to day. They were always haunted by instructors who didn’t feel they belonged there. Classmates treated them like they were invisible.”

Except for all-black universities in the South, little opportunity existed for blacks in higher education. Those who did get into white schools faced extraordinary segregation, Lewis says. A. Leon Higginbotham, who would later become a federal judge, was forced to sleep in an unheated barn at Purdue, before transferring out.

Helen Faison, co-valedictorian at Westinghouse with Poole and director of the Pittsburgh Teachers Institute, remembers an unending wait for racial parity.

“Back then, you always hoped that it would end, and at some point that everyone would realize that people are people and should be treated equally,” says Faison, who went to Pitt during those years and later became acting superintendent of the Pittsburgh School District, the first black woman to hold the position.

Those blacks who did get in were the cream of the crop. “They had to be exceptional students, way beyond the standards required of other students,” Lewis says.

Johnson Davis, Poole and Frye fit that bill. They were raised by men and women who had come of age in the Jim Crow South, who insisted their children become “somebody.”

After her own mother died, Poole was raised by her aunt and uncle, living with her older cousin, Gertrude Johnson Wade.“They wanted us to become somebody and make our mark on the world,” says Johnson Wade, who later became the first black female principal in the Pittsburgh school system.

Johnson Wade said her parents came from a generation of Southern blacks for whom slavery was a not-too-distant memory. “A lot of parents had histories — of being on plantations — and they had the real desire to see their kids make it.”

Edward Lee Johnson, the man who raised Poole, came to Pittsburgh in 1903 from Virginia, with a 4th-grade education. He died at age 100 in 1985, having worked 50 years for the Post Office. Poole’s aunt, Laura Belle Johnson, had come to Pittsburgh with an 8th-grade education.

“They had limited formal education but were very wise people,” she says. “There was no question that [Gertrude] and I were going to go to school every day, do well in school every day and go to college. We were never told that. We just knew that they expected it, and we did it. It was as simple as that.”

Johnson Davis’ father, Theodore Johnson, came to Pittsburgh from Georgia with a third-grade education. While working as a garbage carrier, he went to school at night. He eventually got a high school diploma and took classes at Penn State. He became a union shop steward and later, a state representative.

“There was always this emphasis on studying and learning in my house,” she remembers.

All three could have gone to all-black schools in the South. In 1942, after Pitt turned her down, Johnson Davis went to Fisk University in Nashville, Tenn. for a year. But Poole didn’t want to leave town.

“I refused umpteen scholarships [from black schools]. I figured, ‘I live in Pittsburgh, I should be able to go to school here.’”

Frye, who’d slept with a picture of Florence Nightingale tacked to the wall above her bed as a child, wanted to work as an Army nurse to support the war effort. But she didn’t want to go South, either.

Luckily for each of them, Pitt changed its tack in 1943. Under pressure from the federal government, the school decided to enroll blacks into the nursing program.

When a classmate of Frye’s challenged the school’s discriminatory practices, the federal government ruled on the side of the student. (The young woman later decided against attending the nursing school.) The government, in need of nurses for the war effort, threatened to pull funding from Pitt’s Cadet Nurse Corps program if it continued to bar black students.

“They wanted that federal money,” says Johnson Davis.

After graduating from Pitt, Johnson Davis went on to have a long career at Magee and the Veterans Administration hospital, where she became head nurse. She wanted to become a nurse after watching her mother go to the hospital time and again while growing up. Poole had grown up giving her mother medicine from a little amber bottle. Her mother died of abdominal cancer when Rachel was 9.

“I would sit there and look at that glass until it was time to give it to her. I felt powerless, helpless, absolutely. I remember thinking, ‘When I grow up, I’ll never feel this way again. I will never not know what to do with someone who’s sick like my mother was.’”

When someone once told her she should go to medical school, Poole thought about her mother. “There was no doctor at her bedside. There were nurses. So I said, ‘I’ll be a nurse.’”

Frye was in church the day the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. She remembers the voices of the newsboys coming from outside, as they barked out the news of the bombing.

“I wanted to be a nurse in the war,” she says. “I never thought the war would end before I finished school.”

By the fall of 1943, the three women were practicing how to administer shots on each other, take blood pressure and shampoo a patient’s hair. In a few years, they would be working in hospital wards.

Once they were accepted into the program, Poole felt confident the three would succeed. “Admission was the challenge,” she said. “Once we got in, we said, ‘We’re smart. We’ll do well.’ I just knew we were going to make it.”

There was no question that each had the drive. Poole, who later earned a Ph.D. in education and became a nursing professor at her alma mater, worked 48-hour jobs in addition to taking a full course load her first year.

Gaining acceptance from white students and faculty was another matter. There were certainly friendly white students. Johnson Davis became good friends with one white student, Rosemary McNamara Kelly. The two took each other home to meet one another’s family. Kelly remembers an assignment at Western Psychiatric, when one of the hospital’s nurses objected to Johnson Davis rooming with white nurses.

“She was from the Deep South, and she thought things should be like the Deep South. The woman absolutely wanted Adena in there by herself,” said Kelly, 84, of Halifax, Pa. “I said, ‘We’re friends and we pick who we room with.’”

But other whites kept the black students at arm’s length, remembers Johnson Wade, Poole’s cousin, who was enrolled in Pitt’s School of Education at the time. “We didn’t get the kind of help and attention that [white] students got. We were just sort of there, so we helped each other.”

Frye and Poole joined Alpha Kappa Alpha, one of the nation’s oldest black sororities. They spent many hours studying in the Cathedral of Learning or hanging out with other black students in the “tuck” shop — ’40s slang for cafeteria — smoking cigarettes and drinking Coke.

Though they had broken the color barrier for nursing in Pittsburgh, Frye and her classmates never stopped to ponder their place in history. “I wasn’t thinking of breaking through. We were just focused on finishing our degrees,” she says.

Yet they knew many eyes were on them.

The nursing school dean called them into her office one Halloween. There was a dance that night for students at the medical and nursing schools. None of the three had planned on attending, but the dean told them to find costumes and show up. The nuns from St. Francis Hospital, who were considering allowing black students into their nursing program, wanted to see how the black students mixed with white students. The dean had one word of caution, however. No dancing with the white medical students.

That evening, dressed in a hastily arranged fortune-teller costume, with the eyes of the nuns on her, Frye remembered feeling a surge of pride. “We knew that other black students were going to be admitted to St. Francis,” said Frye, who later earned a Ph.D. and taught mental health nursing at Pitt.

The scrutiny didn’t end there. A janitor told Johnson Davis that the nuns had been through her dorm room, inspecting her housekeeping abilities. They found the room spotless.

“When I was growing up, we always had to leave everything clean. You made that bed in the morning. When you left for school, that room was in perfect shape.”

St. Francis integrated its nursing program shortly after Pitt.

Signs of racial prejudice were not hard to find for the young women.

“One patient said to me, ‘I want a real nurse,’” Poole remembers. “I said, ‘You got one right here, so let’s get going.’”

While on an assignment in Braddock, Poole tried eating lunch at a restaurant there but was turned away because she was black.“I took it to the magistrate,” she remembers. “And the university was furious with me. They told me I needed to quit, or they would expel me. But I was very stubborn.”

The threat of expulsion frightened her. “As a young black woman, I had no power, whatsoever, none. And I’m being threatened by the dean and the chancellor. I had worked hard for five years, and I only had a few months left and they were going to expel me for standing up for my rights.”

Eventually, the school backed down, and Poole kept her academic standing.

Pitt’s current dean of nursing, Jacqueline Dunbar-Jacob, says she marvels at what the three women were able to accomplish. “They did it without alienating others. They did it in a way that allowed others who had been saying no to them to step back and say, ‘Gosh, I wonder why we said no to these people?’”

All three women are active in the school’s alumni association and in recruiting blacks into nursing. Pitt named a scholarship after Johnson Davis, which goes to a promising African American student.

In spite of their trouble getting in, the three women harbor no ill will toward their alma mater, the first nursing program in Pittsburgh to accept black students.

“I was proud of Pitt for letting us in, no matter how they let us in,” Frye says. “Because they were the first.”