In his Westmoreland County office, Scott Tomlinson displays a photo of four men with camouflage-painted faces and a pile of dead deer in their blue pickup truck. As a state wildlife conservation officer, Tomlinson has apprehended dozens of poachers over the years, and the image has come to symbolize the bravado he has encountered again and again. Shoulders squared, rifles at their sides, the men peer proudly into his camera.

Two are grinning. Having their picture taken with the officer who had just cited them was their idea, and Tomlinson obliged.

“I figured it could help me at a later date if they failed to pay their $5,000 fine, which is exactly what happened. They were a bunch of old boys who came up from Pittsburgh to drink beer and shoot deer in Somerset County. It was the day before deer season opened, and they didn’t think anyone would be watching. We fooled ’em.”

Former Game Commission Officer Tom Fazi has a photo, too; this one of an antler addict. “This guy was one of our more notorious cases, because he’d been caught many, many times,” said Fazi, now an information and education supervisor for the commission’s southwest region. “His hunting license was already on revocation to the year 2036 when I caught him poaching a buck. The first thing he said when I busted him was, ‘I’m addicted to racks. Show me a big rack and I’ll show you a dead deer.’’’

The stories are countless and so, it seems, are the people who buck the rules when it comes to killing white-tailed deer, turkey, black bear and even squirrels, rabbits and other small game. Although the commission prosecutes more than 1,000 big game cases a year, many more go undetected by the agency’s law enforcement corps. In a state with almost 1 million licensed hunters—only Texas has more—there are just 200 officers and another 450 volunteer deputies to patrol state game lands, forests and fields, often in the dead of night and far from civilization. Poachers run the gamut from thrill killers to antler hoarders to black marketeers who deal in meat and other animal parts, such as bear gall bladders and claws, which are coveted overseas.

“Some poachers are psycho,” said Fazi, recalling those who keep diaries with chilling accounts of every deer they kill, typically slicing off the antlers and leaving the rest of the animal to rot. Some violators see poaching as competitive sport, often vying for the biggest buck on barroom bets. Others shoot deer out of season for summer barbecues or exceed the bag limit during the fall hunt, claiming they have a hungry family to feed. “That’s a lame excuse, but we hear it a lot. ‘I’m destitute. I’m out of work,’” Fazi said. “But could those same people justify holding up a Sheetz for $500? Stealing is stealing. That’s the bottom line.”

Yet folks who wouldn’t pocket a candy bar from a 7-Eleven have a sense of entitlement when it comes to wild game, he said. “There’s the stereotype of poachers as backwoods hillbillies, but we’ve caught preachers, doctors, lawyers, teachers, you name it. Our game law is one of the most socially acceptable laws to break.”

Until recently, it also was one of the weakest, with penalties allowing for no possibility of jail time, even for the worst violators. In July, after a three-year battle with the National Rifle Association, state lawmakers passed legislation that now provides for incarceration as well as stiffer fines and longer periods of hunting license revocation, even for first-time offenders. And while the new law contains a felony statute for serial poachers, it was crafted with language that allows Pennsylvania Game Code felons to keep their guns. “Threatening to take away someone’s right to bear arms made me nervous because it’s truly one of the most valued rights we have. It made my colleagues in the Senate nervous, too,” said Sen. Richard Alloway (R-Franklin), who sponsored an 11th-hour, NRA-backed felony-language amendment on July 3. “It was the only way we could get the votes needed to pass the bill.”

Although legislators insist federal authorities will pick up any slack created by the game code loophole, there are skeptics. “Relying on the federal Department of Justice to bring subsequent criminal action based on a quasi-felony conviction in the game code is a fool’s errand,” said Steve Stallings, a former U.S. Attorney now in private practice. “Even if it gets to that point, the wishy-washy language in the game code provides built-in ammunition for defense counsel.” Regardless, heightened penalties, even for summaries and misdemeanors, will be a major deterrent if magistrates and district attorneys exercise the full measure of the new law, said Rich Palmer, the Game Commission’s chief law enforcement officer. “For the guys who, when the bars close, decide to go on killing sprees, getting caught used to be no big deal—the same as getting a traffic ticket. Now, with serious jail time, they’ll probably think twice.”

All wild birds and mammals—from blue jays to elk to snowshoe hares—are managed by the commission almost entirely with revenues from hunting and trapping license fees. Some additional support is generated by a federal excise tax on the sale of sporting arms and ammunition, as well as proceeds from the sale of oil, gas and timber on game lands. And while bird watchers, photographers and non-hunters enjoy wildlife too, the commission receives no money from the state’s general fund. The commission sets seasons and bag limits on game species in an effort to balance populations with habitat health and hunter demands. A $20.70 license allows the annual harvest of one antlered deer, one spring gobbler, one fall turkey, plus coyotes and small game, including rabbits, pheasants and squirrels. Doe tags are extra. Separate licenses must be purchased for black bear, migratory birds and furbearers such as foxes, while lotteries are held annually for a limited number of elk permits.

Hunters also must follow rules about which sporting arms can be used—from bows to shotguns to muzzleloaders—and are restricted from practices considered a breach of “fair chase,” such as baiting wild game with piles of food, shooting from cars or stunning deer with spotlights in order to kill them at night, a serious crime known as jack-lighting. A 707-pound bear was illegally harvested last fall in the Pocono Mountains by a man who lured the trophy-size male with a truckload of pastries.

Greene County Wildlife Conservation Officer Rod Burns still thinks about the majestic buck that managed to elude hunters all season, only to be jack-lighted in a field one winter night by a local man with a history of violations. “He killed the buck right there,” said Burns, slowing his truck and pointing to a clearing on land owned and posted by a coal company. “Just killed it and let it lay.” Burns is assigned to one of the most heavily hunted—and poached—counties in the state. Deer are intrinsic to its rural culture, serving as sustenance, sport and a kind of currency for the very poor, some of whom trade antlers or meat for drugs or guns. Children learn to hunt when they are 5- and 6-years-old. Schools close for the opening day of rifle season, when restaurants begin serving breakfast at 3 a.m. “I look out my window and see cars bumper to bumper and wonder how many of these people I am going to meet before the day’s over,” said Burns. “I estimate that for every 10 deer shot legally, there’s three or four… where there’s some illegal act involved. It’s that bad.”

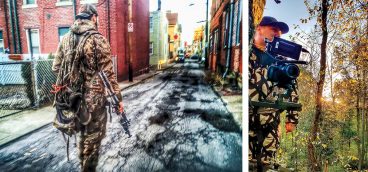

At the end of a long, hot summer, when bucks are shedding the velvet from their racks and chilly nights are prompting them to move, Burns steps up his patrols because poachers are likely to begin stirring, too. He and deputy Steve King take a series of winding roads through Greene County’s abundant forests one night during Labor Day weekend to arrive on a secluded hill overlooking fields frequented by poachers. They cut the motor of their truck and wait beneath the star-filled sky for a spotlight to shine from the road below. Before long, someone in a slow-moving vehicle illuminates the silent fields. Spotlighting to watch wildlife is legal until 11 p.m. in Pennsylvania, but when the beam becomes fixed on a single spot—having found, perhaps, a trophy buck—the officers raise their binoculars and wait for the sound of a rifle blast. It never comes.

“Maybe he was just looking,” King says, “or maybe his better judgment kicked in.” He and Burns, nonetheless, head down the hill and catch up with the car, which is licensed in West Virginia. They casually ask the driver what he’s seen—“ain’t seen nothin’ but a bunch of does,” he drawls. The officers check the back seat for a firearm. Finding none, they bid the man good night and head to another hill. In the weeks ahead, when deer hunting starts, nights like this will be more eventful, Burns said. “It’s good that people see us out and about. They know we’re here and we’re watching.”