Theatrical advertising today tends to overpromise and underdeliver: old classics are repackaged in the wrappings of contemporary mores, new works are compared to old classics, and hype is so prevalent in promotional campaigns that the laconic nature of Barebones Productions’ marketing for “The Sound Inside” (2018) made me really pay attention. It did not tout the usual “hip-hop-Shakespeare-gender-reversed-political-didactic” spectacle that many plays pitch these days. The title was vague, the imagery abstract — imagine a foggy windshield — and no claims were made for a consciousness-changing experience. This should be interesting I thought, as it really takes guts to avoid hyperbole when precious ticket sales are at stake in our post-pandemic world.

And boy was I right. In fact, following Barebones’ example, I really shouldn’t say anything else; rather I should simply urge you to see this production on faith, so that you can absorb the same exquisite uncoiling of this performance as I did — knowing nothing beforehand — like a campfire story told late at night.

Thus, if you desire to read on, I promise not to reveal any spoilers, but I may inadvertently give you a little knowledge in the Garden-of-Eden-sense that may alter your perspective. So, if you have a craving for apples, please read on.

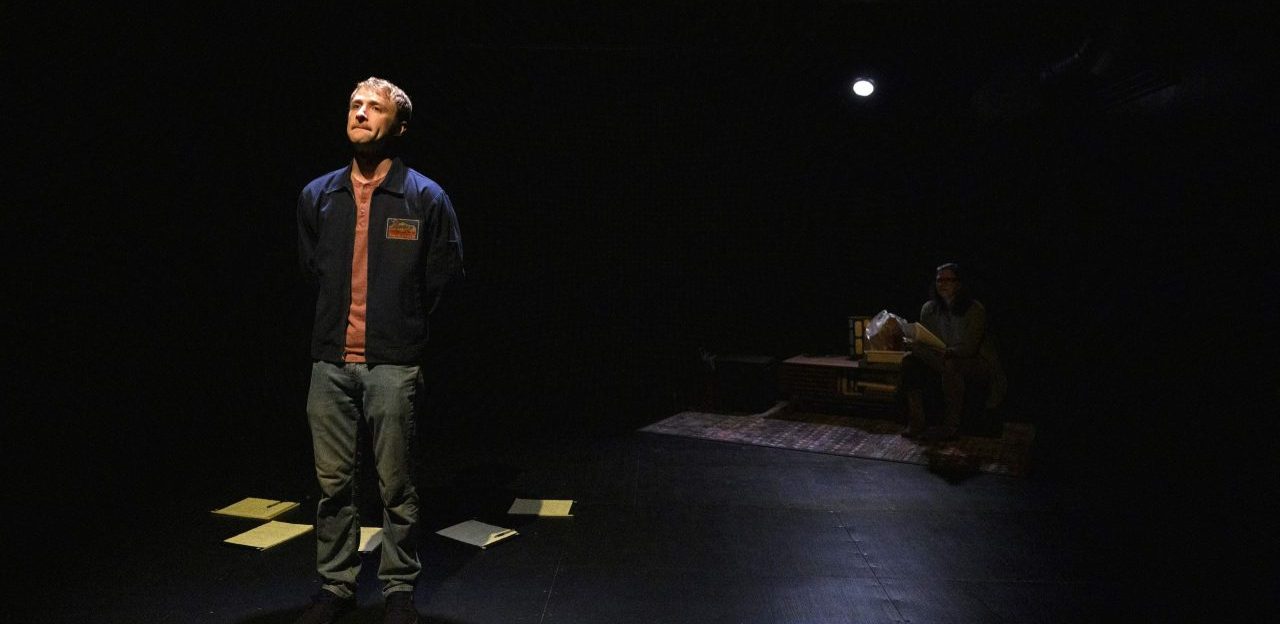

We are presented with a black stage — made even darker as Barebones performs in a black box theater — with the kind of focused, spotlight illumination that intellectual television productions from the 1960s used to convey intensity. Think of the David Susskind show. Lighting designer Andrew David Ostrowski utilizes this not only to amplify the more somber aspects of the story, which involve discussions of cancer, death, and Dostoevsky, but also to create the illusion of space, as what isn’t lit isn’t seen, and hence conveys the impression of infinity.

As the character Bella (Elena Passarello), a Yale professor, appears from the darkness and begins to narrate, we immediately feel as if we’re witnessing a Cortázar or Borges tale — that is a story-within-a-story which jumps between narration and action sans caesura, like the snappy dialogue of a Howard Hawks film. When the second character, Christopher (Max Pavel), her student, enters, he does the same, continuing both the narration to the audience, and dialogue with Bella. It’s like being inside the magic of a children’s story and experiencing two dimensions at once.

This is all a modernist conceit and somewhat refreshing, if not recrudescent, in our post-modernist theatrical world. In fact, Tony Ferrieri’s set looks like the severely minimalist living room of a character from a Samuel Beckett novel. Ferrieri is known for his innovative and often colossal design evocations, so the setting feels like a character — or in this case a designer — playing against type.

Without giving away the plot, what develops is the classic teacher-student motif, with Bella dominant in the social role, but is she dominant in their psychological dynamic? Each time we think we know the answer, things seem to reverse.

Director Patrick Jordan has chosen two actors who may be the most well-suited to their parts you’ll ever see: Passarello’s Bella projects an academic-world-weariness that avoids contrivance, while Pavel’s Christopher registers the kind of sophomoric self-assuredness we have all witnessed in real life. These are not mere affectations of staged persona. To their credit, neither actor is trying to convince us of anything; they simply are who they are without overselling it.

We know we’re in a state of hyperreality when days, weeks, and months pass, but neither character changes costumes. Are we really seeing a story play out before us, or is this the imagining of the characters themselves, perhaps their dreams being projected the way certain lines are projected on the back wall as they are spoken? (Sergio Leone employed this question brilliantly in his masterful film, “Once Upon a Time in America”).

Any of this is possible as the playwright, Adam Rapp, drops more literary references than a recent ivy league grad at a pickup bar on Manhattan’s upper East Side. Rapp — through his characters — cites writers such as James Salter, Yukio Mishima, Beckett, Dr. Seuss, David Foster Wallace, Hemingway, Virginia Woolf, and the list goes on. If you like literature you will love the dialogue because Bella and Christopher are not souls who live in the world; they read about the world. They are inherently suspect of anything that does not exist on the page.

The show runs without intermission for a brisk 90 minutes and, although it doesn’t feel uncomfortable, it does suffer from what I would call stage-time concision, which is kind of like film-time concision, whereby time itself is condensed in the way we think of “dog years” being condensed. Statements do not always linger in the air; characters do not always mull over what they hear; decisions are made in an instant when we know they would take more time in actuality. This kind of jury-rigging of the Einsteinian space-time continuum was what the old film studios used in situations such as the “meet-cute” — when two characters meet and instantly fall in love because time is money and the studio needs to move on to the next scene, where Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney go on a hayride together.

I mention this because there are two key “aikido moments” in the play where the balance of things shifts in such a major and sudden way that it feels rushed, as if we should be entitled to witness a stronger beat in the action, so that the change would feel more like the characters’ doing than the playwright’s.

Usually we encounter films that started out as plays, and we can spot this origin, as it’s in the fabric of everything, from the dialogue, to the sets, to the acting. The recent movie “The Whale” is a good example, or more famously “Glengarry Glen Ross.” You sense this intuitively. “The Sound Inside,” however, has the essence of a film that’s struggling to become a play. It’s as if Agnès Varda’s “Vagabond” tried to merge with Hal Hartley’s “Surviving Desire,” with the jump cuts of Jean-Luc Goddard’s “Breathless” thrown in for dramatic effect when the narration suddenly clicks back-and-forth to dialogue. This is neither good nor bad, but it certainly makes for a very intense kind of theatrical experience.

A lot more is told than shown in “The Sound Inside” which normally I would call a bug, but in this case is a feature. And as I stated, I don’t want to ruin the experience of seeing this play by giving away too many details, or by providing the usual feckless plot summary offered by so many critics.

Rapp is a superb writer and Jordan a gifted director, thus, with two actors who are able to thrive on the pregnant concision this playscript demands, they pull off a show that will leave you in its powerful afterglow long after you exit the theater and stumble back into the relativity of your own non-fictional life.

THE SOUND INSIDE continues through August 26th at the Barebones Black Box Theater, 1211 Braddock Ave., Braddock. $40-50. www.barebonesproductions.com