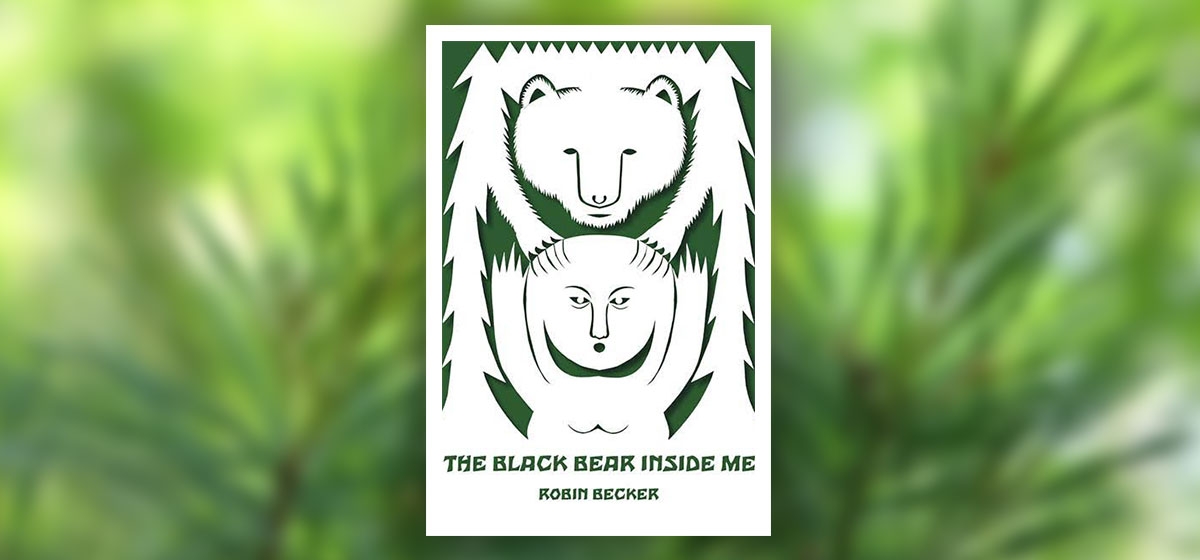

The Spirit of Animals Glows in Robin Becker’s “The Black Bear Inside Me”

There’s a favorite scene in Don DeLillo’s sprawling masterpiece of a novel, “Underworld,” where a priest asks his student to name the parts of the boots the pupil’s wearing. The young man struggles with the assignment, allowing the priest to walk him through each aspect of this common accessory, an extension of the body, saying “How everyday things lie hidden…everyday things represent the most overlooked knowledge…quotidian things…an extraordinary word that suggests the depth and reach of the commonplace.” It’s with this eye toward discovery and an attention to detail that poet Robin Becker brings a rapturous use of language to her eighth full-length collection, “The Black Bear Inside Me,” recently released by the University of Pittsburgh Press.

Becker, a professor emeritus in English and Women Studies at Penn State, has been publishing since the early 1970’s. The esteemed Pitt Poetry editor, Ed Ochester, has called Becker “…the foremost feminist poet of her generation.” A winner of numerous awards, including the Lambda, she also serves as poetry and contributing editor for The Women’s Review of Books.

As a pet owner, animals figure prominently in several of Becker’s poems. In a brief interview with The Minnesota Review, when asked to pick an alter-ego, she replies, “I choose a dog because a dog communicates without words, loves deeply, and does not know that he/she will die.” It’s in this vein that she writes in “Semblance,” “The dog I love is turning into my father/ an old man I have to humor to get up/ do his business…// snoring like my father who/ never had much use for my conversation// and showed his teeth when I displeased him…” The last line of the poem has the dog “eat[ing] from my palm,” an act of kindness owners of older, fussy dogs might know well, painting the speaker compassionate while gaining insight into her paternal relationship.

“The Collection of the Canter” delves into Becker’s pre-adolescent equestrian past as she drops the reader into a memory evinced “by the smell of Absorbine/ and hoof dressing rose astringent from the cross ties.” The poem enters with detailed scenes of a sport inaccessible to most, filled with action and reflection. The highlights coming in lists of specialized language, “D-Ring Snaffle and Rubber Pelham, Kimberwicke and Hackamore,” that ring with a sense of musicality the speaker enjoys as well, including “Throatlatch, cavesson, brow band, laced rein.” Ultimately, the poem and the memory it stems from is less about hobby and more about class, “the tack room” having a pecking order where, “you waited, belonging, with the others for your ride home.”

“The Black Bear Inside Me” also bends towards the naturalistic. In “Clearing,” the speaker picks “paintbrush hawkweed and daisies” in the octet of a strong sonnet, with the volta, the turn in the poem, coming on more introspectively when she considers that “to live in the present/ requires we let go every second of our lives.” Perhaps, it’s this perspective that allows her to understand her interactions with animals in more personal ways, as in “Whitetail Spring” and “Hummingbird.” Both poems extract a sense of awe through imagery by not letting readers look away from the struggles in the natural world that are all too easy to forget, with most species needing to live in the moment for survival.

As the literary force of Modernism, poet Ezra Pound espoused that “the natural object is always the adequate symbol.” Becker embraces this ideal in poems like “Make It Plain,” an elegy for a friend. The poem focuses on the speaker picking wildflowers using her friends “old Field Guide…// your handwritten life list/ betrays you as a lover of the world.” Again, Becker allows the specific names of things to accumulate, writing of “goldenrod,/ a nodding thistle, baneberry, hawkweed.” before giving us a glimpse of her friend’s life, “pulling off the road in mid-July/ to jot down sundew, pitcher plant, toadflax,//…This search to match a flower to its name/ can lend a certain order to the day/ as well as give a shape to solitude.” It’s an existential moment that doesn’t get bogged down in abstraction, instead allowing the image to shape the emotion.

And while the collection’s 61 tidy pages are neither overly confessional or political, there are moments of both. In “Bluefish, 1970,” Becker writes of the distant memory of “desire thrumming the narrow/ streets and the clamorous angles of Provincetown(‘s) /… my nightly trip to the women’s bar/ to disco to cigarettes and the compulsive disappointment of leaving/ alone at 2 a.m.” It’s a revealing memory that points to the universal frustrations of the young, seeing others having all the fun.

In the title poem Becker personifies Ursus americanus, writing “All summer I elude them–/ who think they want to see// my three cubs someone/ said she spotted// on the gravel road that severs/ thick woods// near a row of mailboxes,/ by the stream//…fearful// when they hear me/ huff or blow.” The poem ends with a warning: “the land// that supports us/ supports them; without us,// adapted to scarcity and woodland/ loss, they’re going down.” It’s a portentous ending to a poem that embodies much of “The Black Bear Inside Me,” as Becker approaches the world she observes here as both compelled by the human experience and wary of our ability to see ourselves as part of something bigger.