The Lay of the Land

Have you ever stopped to ponder to what extent anatomy — or more correctly, topography — is destiny in the historical development and popular perception of Pittsburgh? Martin Aurand has. In an ambitious, new publication from the University of Pittsburgh Press titled “The Spectator and the Topographical City,” he endeavors to explain how three of the city’s “topographical rooms,” defined by their features, have come to define the city.

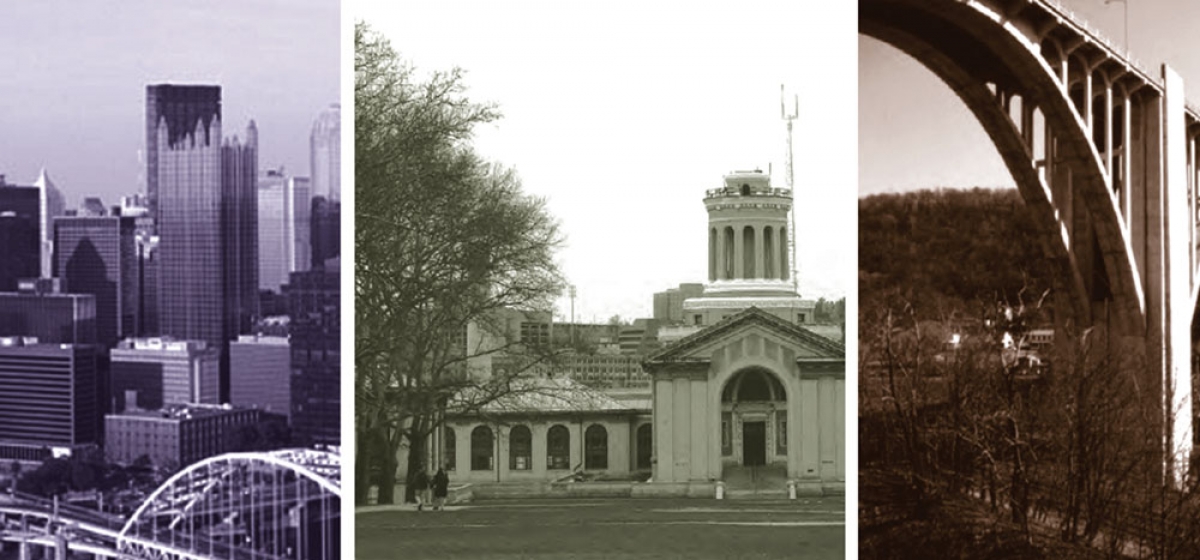

Two of these “rooms,” Downtown and Oakland, are the city’s metaphoric front parlors. The Turtle Creek Valley, which spills out from beneath the Westinghouse Bridge into Braddock and along the shores of the Monongahela, is the city’s back doorway; more a corridor than a room.

As recently as a generation ago, all travelers from the east, arriving either by rail or transcontinental Rte. 30, were confronted in this valley with an experience of the Technical Sublime. The monumentality of the bridge, the vast extent of the rail yards, the sheer physical presence of the Edgar Thomson works and the ceaseless energy of industry at both U.S. Steel and Westinghouse evoked in those spectators feelings of beauty, awe and “wonder sometimes tinged with fear.” Contributing to this effect was the geography of rivers and hills, which reflected the fires of the furnaces and encompassed a “perpetual pall” of smoke and ash. The result of this unwitting collaboration of natural and manmade elements was the eerily romantic visual effect which fascinated artists and characterized Pittsburgh throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. The bucolic beauty of quaint Turtle Creek was destroyed. But few mourned it, for in its place was something larger, more meaningful, and more identifiable with Pittsburgh.

In his discussion of this iconic industrial area, Aurand also illustrates an important point about the factory and the mill as building types; explaining their evolution from repositories of machinery into a kind of machine themselves. By extension, the whole of the Turtle Creek Valley is best interpreted as a machine; one of the great engines driving the progress of Pittsburgh and the nation.

By contrast, Oakland was the city on the hill, literally and symbolically; a paragon of cultural and civic virtue supported by the labors of the industrial machine. Situated on the high bluff of Pittsburgh’s East End and constructed on relatively level ground formerly occupied by cabbage fields, this was the city’s “Fifty Million Dollar Beauty Center,” an architectural showplace and recreation ground designed to “civilize and elevate its inhabitants by means of urban planning.” Constructed nearly all at once in the first decades of the 20th century, it remains an enduring testament to the City Beautiful Movement that arose in response to the rapid and chaotic urbanization of the country. In compensation for the abusive excesses of the industrialized valleys — both social and environmental — Oakland represented a kind of symbolic reward for the laborers who toiled therein; a place to refresh mind and spirit, consciously set in a landscape of open green space.

Curiously, Aurand omits any discussion of the enhanced naturalism of Oakland’s Schenley Park, concentrating instead on architect Henry Hornbostel’s vision for Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon University), and his abandoned “acropolis” plan for the University of Pittsburgh. Aurand, Architecture Librarian & Archivist at CMU, shows an understandable chauvinism in his analysis of that school’s design. He pulls out all the stops to prove it “one of the great sites of American architecture, landscape and urbanism;” referencing Italian Renaissance villa design and theatrical perspective, French Baroque gardens and Jefferson’s University of Virginia scheme. Particularly compelling is his depiction of the plan as a “court of honor” inspired by the beautiful “White City” of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

Both the idealized Oakland and the industrialized Turtle Creek Valley represent singular, cohesive entities expressing discrete aspects of the city of Pittsburgh. Downtown, however, is a hybrid; and consequently the richest and most complex of Aurand’s three rooms. As the place of earliest settlement in the region, it is layered with centuries of topographical, functional, architectural and social change, and its vicissitudes reflect the long history of a search for self-definition. The author describes with authority and enthusiasm what few people pause to consider: the transformation of the area from an ancient burial ground to a defensive European post, to a mercantile center aspiring to be the City of Tomorrow.

More than the other locations, the natural features of the so-called Golden Triangle defined and dictated its development. The apex of the triangle was the site of the forts which established permanent settlement in the area. The rivers on either side prompted the imposition of two separate grids, which collide along Liberty Avenue in what the late Walter Kidney cleverly referred to as a “tartan” street plan, resulting in unconventional lots, visual density and spatial confusion at city center. The base of the triangle, along the eastern boundary, was originally not the great bluff referred to today as the Hill District, but a smaller, rounder hill which stood at its base. This hill, dubbed Grant’s Hill during the French & Indian War, once served as a burial mound sacred to the prehistoric peoples of the region. In later years it acted as a popular pleasure ground for city dwellers and provided a pedestal for the earliest courthouses. When it became an obstacle to commercial expansion at the turn of the last century, it was graded into obscurity in what was unceremoniously referred to as the “hump cut.”

Civic boosters are sure to appreciate the author’s analysis of this forgotten hill in cosmological terms; describing it as the “navel of creation;” the “place of connection between heaven, earth and the underworld” that secures Pittsburgh a place among the “cities at the center of the world.”

Beginning with the construction of H.H. Richardson’s famous county buildings of 1883-88, architecture supplanted natural formations as landmarks in the triangle, providing the area’s vertical emphasis. Eventually commerce “replaced the church and civic authority in the skyline,” and visibility became a “commercial value in a contest that required more and more initiative to stand out.” The plutocrats of Pittsburgh found themselves engaged in a real-estate war of high-rise construction; vying for architectural distinction in a battle of egos, or what Aurand calls “personal giantism.”

As commercial structures grew in height, the spectator’s point of view changed. No longer was the observer perceived as standing below and looking up, but rather as above looking down on the city. In the 1930s, design and development was even influenced by the aerial perspective afforded to airplanes en route to and from the new Allegheny County Airport. Unfortunately for downtown Pittsburgh, its picturesque qualities —- the dense plaid pattern of streets, the opaqueness of its sooty air — lost their charm when seen from above. The features which for years represented prosperity now branded the city as anti-modern — the antithesis of the clean, regulated spaces of the radiant city advocated by visionaries like Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright. The view from the high-rise executive offices became an affront to the progressives who occupied them, and Downtown entered a new era of urban renewal, resulting in features such as Mellon Square, Gateway Center and Point Park.

Today, Point Park forms the tip of a three-dimensional “urban wedge,” rising from river level at the head of the Ohio to the heights of the U.S. Steel Building at its base; a golden triangle in mass as well as plan. This perspective, seen to its advantage in postcard images from atop Mount Washington, is the ultimate spectator’s view: the city’s “urban advertisement to the world” and a “vehicle of communication with a consumer audience.”

Aurand wisely refrains from making a value judgment about Pittsburgh as a commodity for the spectator. That is a subject for another tome. However, having been invited to consider the city in a new way, one can’t help but wonder how the experience of the phantom spectator — the outsider’s perception — came to mean more to Pittsburgh than the day-to-day experience of the tax-paying man on the street. Why does the city care so much about what other people think of it?

Perhaps one day The Spectator and the Topographical City will be complemented by a second volume titled “The Resident and the Topographical City,” which will deal not only with our distinctive neighborhoods of hills and hollows but also with the legacy of our extensive and expensive infrastructure. (Talk about wonder tinged with fear!) In the meantime, Aurand’s book allows the reader to play the coveted role of spectator, to take a good look at our city and “cherish the vision” of a “familiar fond icon”: Pittsburgh.