In the language of golf, there is always a “hidden gem.” The hidden gem is a golf course that is little known or even unknown, that someone has visited and then pronounced a marvel. The course generally has been sitting there, probably for many decades, known but to the locals.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”31″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

It could be a Ross, a MacKenzie or a Tillinghast (courses take the name of their creator just as paintings are a Rembrandt, a Van Gogh or a lost Caravaggio), or one of the others in the pantheon of great golf course architects. A hidden gem is usually discovered by a public relations move to drum up business or a golf snob who chanced upon the place and is eager to drop a new name. In the case of Foxburg Country Club, none of this applies.

Foxburg Country Club, near the small town of Foxburg in Clarion County, sits high above a forested bend of the Allegheny River, about two hours north and slightly east of Pittsburgh. It’s just off Interstate 80, at Exit 6. But the name is deceptive. Foxburg is to the country club what a bicycle is to a Ferrari. Foxburg doesn’t have the atrium of Fox Chapel (no relation), the opulent clubhouse of Medinah, the frightful greens of Oakmont or the majestic, supplicating pines of Laurel Valley. Foxburg doesn’t even have 18 holes. Just nine holes, 5,219 gently rolling yards for two trips, par-68 and no pretenses.

What Foxburg does have, though, is history. Foxburg was there before all of them: before Shinnecock Hills, playground of the Hamptons; before The Country Club at Brookline, retreat of the Boston elite; and before Newport Country Club, sanctuary of the Astors, Vanderbilts and all the rest.

Foxburg is the oldest golf course in the United States, dating to 1887, though it prefers a less assertive title. Foxburg takes its billing from its Pennsylvania roadside historical marker: “Oldest golf course in continuous use in the U.S.”

(Everything “Fox,” by the way, was named after the patriarch of the family, Philadelphian Samuel Mickle Fox, who acquired some 118,000 acres in the area.)

Golf came to Foxburg by way of cricket. In the mid-1800s, cricket was the big game among the wealthy clubbers of the Northeast, who frequented such places as the Pittsburgh Cricket Club, forerunner of the Pittsburgh Field Club. As avid as any player was Joseph Mickle Fox, great grandson of Samuel, who had the family summer estate at Foxburg. In 1884, Fox was with the Merion Cricket Club team for a series of matches in Britain, and he went to St. Andrews, in Scotland, to see what this golf was all about. He met Old Tom Morris, iconic patriarch, and came away converted. He bought some clubs and balls, and when he got home, he laid out a rudimentary course on the grounds of his estate. He and friends played golf on this course for three years. The game caught on, and in 1887, he built what is now Foxburg Country Club. There certainly was no lack of people who could afford to play golf. This was oil country at the time.

But times and fortunes change, and eventually Foxburg CC became what it is today, a modest semi-private public course where friends gather to play golf.

“We’re not loaded with doctors, lawyers and CEOs,” said David Middleton, Foxburg CC president and a former guidance counselor and golf coach at nearby Allegheny-Clarion High School. “We’ve got businessmen, teachers and blue-collar guys. And we’re getting more outside play. Thanks to our web site, we’re getting people who are interested in golf.”

And for the golfer who’s just played Oakmont and Pinehurst and Ballybunion, perhaps a dollop of contempt would be in order.

“In all the years I’ve been here, I’ve never heard anyone knock the course,” Middleton said. “Maybe they were just being discreet, but all I’ve ever heard was highly positive.”

Foxburg CC has some 140 members, and like golfers at any other public course, they rush in after work for a quick nine on league night and have a few cold ones later.

“We don’t play golf thinking about the history around us,” Middleton said. “We love our course, and we just play golf.”

The membership fee is a mere $660 a year, about a 10th of what it costs at more prominent clubs. For public play, the green fee is a soft $25 on weekdays and $30 on weekends, cart included. That’s for 18 holes. You go around twice, playing from different tees the second trip.

“Foxburg may be short,” Middleton was saying, “but they don’t tear it up.”

Foxburg is a neat, well-kept and uncomplicated layout. It has no cavernous bunkers, no wrenching doglegs, no forced carries. Foxburg has a most unusual configuration — five par-4s, one par-5, and three par-3s. The long holes run back and forth, paralleling each other, and the par-3s were tucked in wherever they fit.

No. 7 is the toughest hole on the course and has a rare look. As a contributor to the Foxburg web site blog put it: “No hole should look so easy and be so damnably difficult. I believe it is haunted!” Which is not an unreasonable assessment for a 300-yard downhill hole that requires a lay-up tee ball short of a set of demonic, shaggy ridges, and then a pitch over the ridges onto a green that falls away.

The greens are all circular and about 26 yards in diameter, except for those at No. 7 and No. 9, which are smaller. The greens are comparatively flat, containing no swells or undulations, and so are puttable, except the one at No. 4, where a 25- or 30-footer from the left, up and over a gentle ridge, somehow rejects the notion of gravity and refuses to break down toward the pin.

Golf appeared in America long before Foxburg arrived. It’s well established in history that the game was played in New York in 1779, South Carolina in 1795, Georgia in 1796 and 1808, and elsewhere. It’s not known whether these were organized clubs with courses or merely groups of people playing informally in a field. Whatever they were, they died out. Foxburg is where golf first took root and stayed.

The original clubhouse, built in 1900, was little more than a big shed. In 1942, a log home next to the course became the clubhouse and still is. All the business of golf is contained in one room. There is no restaurant and no bar. There are no racks of equipment and stacks of golf apparel. Foxburg doesn’t have a golf pro, either. You can buy a logoed golf shirt, a club, a bag, some balls, a hot dog, a candy bar, a soft drink, pay your green fee, pay for your cart and head out. The living room is large and empty. The second floor is given over to the American Golf Hall of Fame, a few rooms of old golf equipment and all that’s left of a plan in the 1970s for an elaborate golf course real estate development by a group that included the late Bob Prince, the famous Pirates broadcaster.

It all began with Samuel F. Fox of Philadelphia, and the vast property he amassed in the 1700s, far away in the wilds of northwestern Pennsylvania. And there’s a mildly roguish tale of how he got started. Legend holds that William Penn, whom Charles II had paid off by giving him Pennsylvania, in turn paid a debt to Fox in in the late 1700s by letting him keep all the land he could walk in one day in what is now the Foxburg area. There’s the hint here that Penn didn’t mind unloading a bit of steep hills and dense forests that he’d never even seen. Fox, in turn, one-upped Penn by hiring the fastest Indian he could find to walk the land on the longest day of the year, June 21. And that, the story goes, was how Fox got his first 1,100 acres.

The tale has the ring of history to it, and it even appears on the web site of the town of Foxburg. It is a delicious tale, but alas, untrue. Whatever Sam Fox’s deal was, it wasn’t with William Penn. Penn had been dead for 78 years. (History buffs will recall, however, that Penn, himself, actually made such a “walking contract” with the Delaware Indians. And in 1737, years after Penn’s death, the contract was measured by a relay team of walkers/runners who traveled much farther in a day than the Delawares, who were giving the land, ever intended.)

The real story, according to records, is that Fox bought the land in 1796 from the Commonwealth, paying “five pounds, six shillings, nine pence” for 1,100 acres, and he received a deed signed by Gov. Thomas Mifflin, first governor of the state. And that was the start of Fox’s 118,000 acres. Great-grandson Joseph came along some 90 years later and built a golf course on a tiny part of it.

Foxburg’s place in golf history didn’t become an issue until about the late 1940s, when some area residents, chiefly Mr. and Mrs. Marcellin C. Adams, needed to document their petition to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission for the historical road marker that sits at the edge of the course. They got sworn depositions from five people testifying to the history of the club, among them Harry R. Harvey, then 80, who helped lay out the course and then served as secretary-treasurer of the club from its founding in 1887 to 1941.

To anyone paying attention, the Foxburg claim sent a shock wave through the serene history of golf. The title of “first golf club” already belonged to St. Andrews of Yonkers, N.Y., which was founded in 1888, a year after Foxburg. And the title of “Father of American Golf” had been awarded to John Reid, a transplanted Scot who organized the group and played the usual rudimentary course — a few tomato cans sunk in a pasture. St. Andrews moved several times and is now Saint Andrew’s at Hastings-on-Hudson.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica notes that two courses could be older than Foxburg. Oakhust Golf Club, at White Sulphur Springs, W.Va., is said to have been formed in 1884. But Charles Blair Macdonald, a curmudgeonly pillar of golf through the turn of the 19th to 20th centuries, dismissed Oakhurst in his book, Scotland’s Gift, Golf, in 1928. He noted that a few holes were laid out and a half dozen men played golf, then added: “The Oakhurst holes were finally abandoned when the Green Briar [sic] course was laid out.” Seemingly like a Brigadoon of golf, Oakhurst returned about 100 years later, billing itself, “Restored for Play in 1994.”

The Field Club of Dorset, Vt., claims 1886, but Britannica shrugs and notes that with both Dorset and Oakhurst, “…written records are lacking.”

Britannica also cites Foxburg’s case and date, then returns to St. Andrews.

The power center of golf from its real birth in the late 1800s was a cluster of Northeastern courses, including St. Andrews — sanctuaries of the movers and shakers of American finance, trade and high society. Macdonald, though out of Chicago, was one of them. This was the group that formed the powerful U.S. Golf Association, the game’s governing body.

Macdonald recognized St. Andrews as the “first organized association of golfers in the United States,” noting that it formed in 1888 and that the club moved to a third course by 1897. Macdonald doesn’t mention Foxburg. Chances are that he never even heard of it.

In the late 1960s, a group of businessmen, mostly Western Pennsylvanians, thought to turn Foxburg’s historical status to a high profit. Real estate developments with golf centerpieces were nothing new, but one with this history would be. Among the entrepreneurs were Bob Prince, whose free spirit would fit the ambitious project, and the late Jack Brand, Pittsburgh insurance man and prominent Oakmont member. The group called the development “Foxview,” and their vision was breathtaking. They would have condos, a shopping center, post office, rental cabins, a lodge and a ski area built on the old Fox estate. The thing fizzled quietly. There was no announced reason, but a lack of money is usually what does these things in.

The course, also called Foxview, was the only part actually built. It was played by a handful of investors, but it never officially opened. Traces of it can still be seen under grass — an elevation for a tee, a bunker. Today it grazes Banded Galloways.

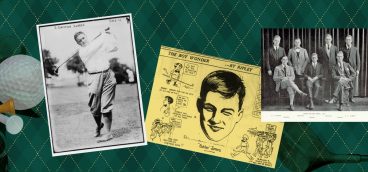

The American Golf Hall of Fame was to be the key tourist attraction in the complex. It was the game’s third hall, but the first all-inclusive, embracing men and women, pros and amateurs and native and foreign golfers. Until the grand building could be erected on the Foxview property, it would be housed modestly on the second floor of the Foxburg log clubhouse, where it sits to this day. The selection committee, including the late news broadcaster Lowell Thomas, Perry Como and Arnold Palmer, selected 15 golfers for the first induction group in 1965. Among them were Bobby Jones, Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, Babe Zaharias and Gene Sarazen. A scattering came over the next six years. The early inductions were held at a motel near Butler, then they moved to the Allegheny Club at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, then in 1979 to a dinner at the Hilton Hotel in Pittsburgh, to welcome Lee Trevino. Then the steam just went out of the thing.

It was a big disappointment to Brand before he died. He left an enigmatic note in a letter to a friend in 1999. “… the whole deal [it] was becoming clear,” he wrote, “that no one at Foxburg CC wanted it to become a reality and enough money had been spent with no results.”

“That doesn’t make sense,” said David Middleton, Foxburg president. “The hall of fame is in our clubhouse. Why wouldnt we want it?”

There is a sense of quiet sadness about it all. The exhibits are still there in a few rooms on the second floor — old golf clubs, golf balls, pictures, Bob Prince’s golf clubs and bag. The honor roll itself is a piece of illustration board, about 24 by 30 inches, with the names pasted to it, and it sits where it fell, curled on the floor of a junk room on the third floor. A guest book shows that people from all over the country and from overseas have stopped in. Admission is free but donations are welcome.

The Tri-State PGA and the Pittsburgh-area club pros also have a room on the second floor devoted to plaques for their various competitions. But that, too, is comatose. The last listed champions are from 1994.

Foxburg remains its quiet self, high above the Allegheny. Nothing will change if Foxburg is declared, once and for all, the first or the oldest or whatever, and nothing will change if it isn’t. But as an academic exercise in sorting out history, the Foxburg story remains tantalizing.

The key to understanding a baffling situation might have best been put forth in an article in the U.S. Golf Association Journal and Turf Management for April 1952, by John P. English, an executive of that ruling body. It is titled, “The Case for Foxburg’s Old Course.” Apparently someone had asked the U.S. Golf Association to set the record straight. English attempts to do so in the article. He lays out Foxburg’s case clearly and concisely on the 1887 founding and then injects a statement about St. Andrews that seems to defy logic:

“It [St. Andrews] has been generally believed to be the oldest permanent golf club in the United States, although other courses are acknowledged to be older.”

Perhaps there are easier ways of figuring this out. One way is to concede that inasmuch as St. Andrews was one of the first five ruling clubs, no one wants to disturb the social order. The other way is to concede that maybe location counts for something. St. Andrews was on the edge of New York City, and Foxburg was on the edge of nowhere.