Second in a three-part series: Even modest exploration of Pennsylvania’s state parks and forests reveals their gifts: hidden waterfalls that appear along hiking trails, imposing rock formations bolted with anchors for climbing, lakes created by dams for swimming and boating on warm summer days, and rivers and streams stocked with fish for the catching. Some offer stunning vistas, such as Leonard Harrison State Park with its bird’s eye view of Pine Creek Gorge—the “Grand Canyon of Pennsylvania”—a rolling 45-mile expanse of densely forested, softly rounded mountains cut by a tumbling stream.

Unlike many other states, visitors can enter and explore Pennsylvania’s parks for free. The parks are economic engines for the towns and counties where they reside. They attract 40 million visitors a year, whose spending accounts for more than $1.1 billion in sales and supports 12.5 million jobs statewide, according to a Pennsylvania State University analysis.

But their balance sheets spell trouble. Maintaining the built and natural environments in a state parks network the size of Pennsylvania’s is a significant undertaking that ranges from tending to campgrounds, bathrooms and roads, to the upkeep of dams and combating invasive plant and insect species that can ruin forests, lakes and streams. The state faces a mounting backlog of such jobs. And the cost of completing them has soared to $1 billion, the Pennsylvania Parks and Forest Foundation recently reported.

It’s a problem that has grown unchecked for at least two decades, one that stands as a threat to the vitality of the state’s parks, which lack a dedicated funding stream for their upkeep.

“We have one of the best state park systems in the country. The heavy lifting wasn’t creating them; it’s maintaining them,” said Len Lichvar, manager of the Somerset Conservation District. “We’ve made great progress in improving them, but to sustain that, we need to improve our funding.”

“We have one of the best state park systems in the country. The heavy lifting wasn’t creating them; it’s maintaining them.”

—Len Lichvar, manager of the Somerset Conservation District

Long-standing dilemma

Managing the state’s parks and forests is no small task. The Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) manages no fewer than 121 parks and 2.2 million acres of forests, and its holdings continue to grow as more land is acquired. And finding the money to maintain them has long been a challenge.

Past studies suggest the maintenance backlog began growing before 1990, when an examination of the parks found that major maintenance projects had been accumulating for at least 15 years. In 2000, a DCNR report identified an unmet need for $50 million worth of road, bridge and dam repairs, sewage and water treatment maintenance, and other projects.

The expansion of the state’s portfolio of parks, the fact most are aging at the same pace and the lack of a consistent source of income devoted to their upkeep has contributed to the maintenance backlog.

Most state parks in Pennsylvania were built during two periods: 1933–1942, when the Civilian Conservation Corps, a Great Depression work relief program, built 700 parks across the United States; and 1955–1979, when Maurice Goddard, a devout conservationist, oversaw the predecessor of DCNR and, later, the state agency responsible for environmental protection. As a result, many state parks require infrastructure improvements at about the same time.

And it’s not only routine maintenance. The popularity of Ohiopyle State Park in Fayette County, for example, prompted a recent $12.4 million project to enhance the safety of the more than 1.5 million people it attracts each year, including moving bike lanes off heavily traveled roads and onto park property, digging a pedestrian tunnel under Route 381, upgrading a bridge and building a new parking lot.

“Some of the things that need to be updated are visible to the public: park roads, a pavilion, making a visitor’s center [Americans with Disabilities Act]-compliant,” said DCNR Secretary Cindy Adams Dunn. “But we also have a lot of non-sexy problems, like aging waterlines. We almost had to shut down Prince Gallitzin State Park last year on July 1 because the water system was losing water due to pipes that were rapidly leaking underground. That’s an expensive fix.”

DCNR can’t count on its share of the state general fund to pay for such repairs. Governors for decades have approved budgets that allocate only a tiny fraction of the state’s general fund for parks and forests. In 2018–2019, DCNR received $121.2 million, about 0.37 percent of the $32.9 billion in general fund revenues the state had available to spend. That covered about one third of the agency’s total budget.

Each year, the state parks earn about $23 million from fees for campground use, cabin rentals and other income that helps pay operating expenses. But more and more, DCNR has had to lean on other sources to cover the cost of operations, which makes finding money to ease the backlog of maintenance projects a greater challenge. Those sources include the Keystone Fund, which awards 15 percent of state real estate transfer tax revenues to state parks, historic sites, libraries, zoos and colleges. Another, the Oil and Gas Lease Fund, supports conservation efforts with revenue from oil and gas leases on state-owned lands.

Pennsylvania’s state parks and forests have also benefited from special initiatives that have received bipartisan support over the years.

Republican Gov. Tom Ridge signed the five-year “Growing Greener” program in 1999, providing $645 million for parks and recreation work, abandoned mine reclamation, watershed restoration and sewage system upgrades across the state. In 2005, Democratic Gov. Ed Rendell signed “Growing Greener II” into law, which gave the initiative another $625 million to spend over six years, including $217.5 million for DCNR with $100 million earmarked for state park and forest improvement projects.

Such temporary pools of money have helped take a bite out of the maintenance needs of state parks and forests, but not a big enough one to stave off a looming crisis. Funding simply hasn’t kept pace with the expansion of the state parks and forests. In fact, it’s remained relatively flat over the past few decades, stunting the growth of DCNR resources available to manage parks and forests. Since 1970, the number of state parks has increased 57 percent and the number of visitors they attract each year has swelled to more than 40 million. Yet, DCNR staffing levels remain roughly the same.

Dams and bugs

Some of the most serious needs in Pennsylvania’s state parks and forests aren’t visible to visitors or residents in the surrounding communities.

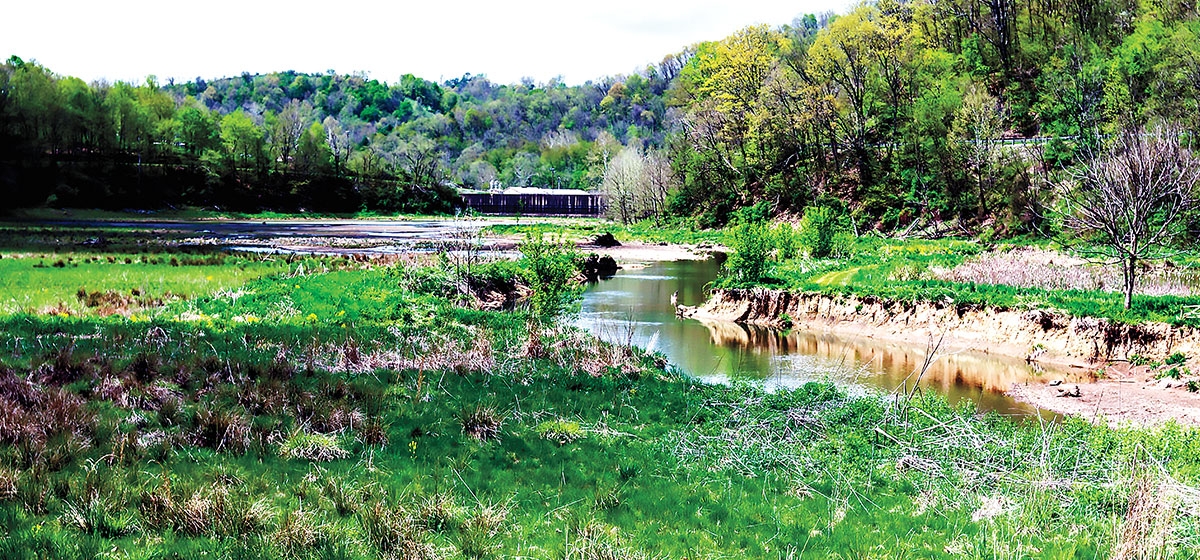

Within the state’s parks and forests are 611 miles of streams that are too polluted to meet federal Clean Water Act quality standards. The average cost of remediating a single mile of impaired stream is $500,000 dollars, according the Parks and Forest report.

“We have a billion-dollar need and about $250 million of that is remediating abandoned mines on state forests,” DCNR Secretary Dunn said. “A huge chunk of the need is a legacy problem. Some of the land that has been brought into the state forest system had abandoned mines on it—strip mines that haven’t been reclaimed. It’s essential to treat the abandoned mine to get clean water coming out of the forest.”

DCNR is responsible for 131 dams in the state’s parks and forests. These include 47 that are considered high hazard and pose a risk of major property damage or loss of human life downstream if they are breached.

In southwestern Pennsylvania, Duke Lake at Ryerson Station State Park Dam in Greene County was drained when the dam that held its waters developed cracks attributed to long-wall coal mining underneath the park. Plans to restore the lake, a popular swimmin/boating/fishing destination, were abandoned due to the instability of the ground beneath. Instead, DCNR is making improvements to its campground and other parts of park, including a new swimming pool.

Safety concerns in the state parks and forests extend to the tops of hemlocks and bottom of reservoirs.

“There’s a lot of infrastructure in our state parks,” said Marci Mowry, president of the Pennsylvania Parks and Forests Foundation. “It’s not just the built infrastructure, it’s the natural infrastructure. We’re talking about waterways, plants.”

Invasive species such emerald ash borers and woolly adelgid dig their way under the bark and destroy some of Pennsylvania’s native trees. Such pests, Mowry said, “are draining the face of our forests.” And, left untreated, the damage they inflict raises the risk of branches or entire trees falling on hikers and campers below.

Hydrilla, an invasive plant, took over the reservoir at Pymatuning State Park, a major fishing destination in Crawford County. The plant kills native plants, disrupts fish populations and jams boat propellers. Its spread threatened to decimate the fish population and tourism at the park and surrounding county. The state spent $150,000 in 2017 to treat the lake. And with a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service grant, the park is installing boat-washing stations to prevent hydrilla from spreading to other lakes.

“Treating an issue at the outset, making the necessary repairs when they arise, making facilities more energy efficient, more resilient to climate—it all helps to ease operating and maintenance costs in the long run,” Dunn said.

New plan, lingering uncertainty

The pool of money available to take such a proactive approach is too shallow to make more than a dent in the list projects that could benefit from it, and the Pennsylvania Parks and Forest Foundation report urges finding a way to address the shortfall.

Additional money for state park maintenance and infrastructure is included in Gov. Tom Wolf’s “Restore Pennsylvania” infrastructure plan announced earlier this year. Wolf, a Democrat, proposes spending $4.5 billion over the next four years to improve infrastructure ranging from high-speed internet, housing and manufacturing to storm water, flood control, parks and trails.

It’s unclear precisely how much money would flow to the state’s parks under the governor’s plan. And its political fate is uncertain.

Wolf’s plan would be funded by borrowing the $4.5 billion and gradually paying it off with revenues from a proposed “severance” tax on natural gas production. Pennsylvania is the only gas-producing state that does not have a severance tax, which is based on the volume of gas produced and adjusted to fluctuations in gas prices. The Wolf administration estimates such a production tax would raise about $300 million a year in revenue. The state currently has a more limited tax on natural gas extraction, charging companies an annual “impact” fee for each well they drill.

“Gas is a natural resource drawn from the ground and shipped out of state,” DCNR Secretary Dunn said. “We’d get an ongoing benefit throughout Pennsylvania in the form of an improved parks system.”

But the idea of imposing a severance tax has repeatedly been opposed by the gas industry and many Republican lawmakers in Harrisburg, who control both chambers of the state legislature. In May, Senate GOP leaders offered a leaner alternative to governor’s infrastructure plan that does not include the need to borrow or a severance tax on natural gas production to pay for it. The GOP plan, like the governor’s, includes spending for state park maintenance. But instead of taxing natural gas production to pay for the improvements, the GOP alternative calls for raising $1 billion in drilling fees by expanding the range of horizontal drilling under state forests, which has been blunted by a moratorium that Wolf imposed in 2015.

In the next issue, the series conclusion takes a closer look at the issues facing state parks around Pittsburgh.