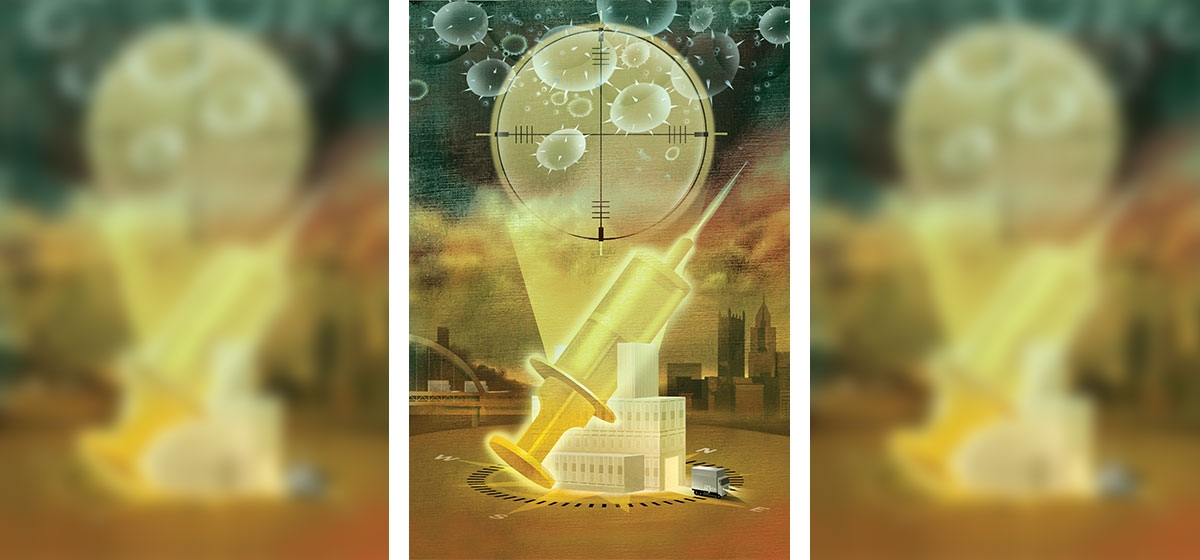

The year is 2020. You’re driving home from work, listening to your favorite satellite radio station. An announcer interrupts with breaking news: Smallpox has broken out in Washington, D.C. Hundreds of patients are flooding hospitals, with untold more infected. The public is panicked. Local officials are scrambling to maintain control.

Everything points to a terrorist attack and federal officials are working day and night to track the source, identify the strain and mobilize countermeasures. All government buildings are closed indefinitely, and all car, rail, and plane travel into and out of the vicinity has been terminated. In an office in Pittsburgh, the Pittsburgh biodefense vaccine facility is in high gear, preparing production of fresh smallpox vaccine.

The last part of that scenario could become reality if the leaders of a broad-based consortium succeed in their ambitious proposal. The group called “21CB”—21st Century Biodefense—is a public-private partnership of legal, scientific, political, healthcare, pharmaceutical and bioterrorism experts that has big plans for both bioterrorism preparedness and Pittsburgh. The consortium has outlined a project to create a Pittsburgh-based, late-stage biodefense vaccine development and manufacturing facility for one customer: the U.S. government. The facility would be designed to be flexible and swift, capable of launching production of a variety of vaccines within 72 hours of a given emergency.

The notion of a vaccine facility in greater Pittsburgh is not entirely new. According to Phil Gomez, Ph. D., President of 21CB and director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/National Institutes of Health Vaccine Research Center, the Pittsburgh vaccine facility concept first was proposed in the early 1990s and again around 2000. At that time, however, neither the demand nor the technology was sufficient to launch the project.

Now, however, times have changed, and it’s no secret that the nation is ill-prepared to combat the range of possible bioterrorism threats. Currently, research and development of a typical vaccine can take as long as eight to 12 years before FDA approval, Gomez said. Only then is a vaccine made in a production facility, and it can take weeks to months to switch vaccine production runs in order to respond to a crisis. Additionally, public health budgets are being cut because of deficits, said Dr. Tom Inglesby, director of UPMC’s Center for Biosecurity. He stressed the importance of preparing now: “Biological events will come again without warning.”

In this context, the 21CB group revived the idea of a Pittsburgh vaccine project in 2008, performing a biodefense “readiness analysis” in conjunction with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). They identified characteristics of an effective biodefense vaccine facility and solicited information from the federal Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Defense, to represent public and military interests, respectively. The ultimate recommendations called for a flexible, on-demand, state-of-the-art vaccine manufacturing facility that could make a reliable vaccine supply at reasonable cost.

Based on the study, 21CB is completing a proposal for the vaccine development and manufacturing project, which would be located Pittsburgh. The actual facility would be between 300,000 and 600,000 square feet and is expected to create 1,000 jobs and lead to another 6,000 indirect jobs. 21CB estimates the project will require roughly $580 million in federal support and another $200 million to $300 million from nonprofit sources.

Its major aims would be threefold: to meet federal specifications for developing and manufacturing multiple biodefense vaccine types; to strengthen the biotechnology workforce base; and to reinforce non-biodefense vaccine manufacturing for the U.S. government and possibly developing nations.

Within months, the federal government is expected to issue a request for proposals, which would include exact specifications for a vaccine facility. Groups across the country will be invited to reply, and 21CB will likely have 60–90 days to complete its proposal. A government decision could come as soon as 30 days after it receives proposals.

If 21CB were to win the competition and build the facility, the benefits to Pittsburgh would be immense. Aside from gaining thousands of jobs, the region could become a major biotech hub, something it has sought and slowly developed for years. Plans are already underway to develop university coursework that would aid in the training of the high-quality workforce that would be necessary.

Developing biodefense, however, is extremely difficult, said Dr. D.A. Henderson, distinguished scholar at UPMC’s Center for Biosecurity and professor of public health and medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. A Presidential Medal of Freedom recipient, Dr. Henderson directed the World Health Organization’s global smallpox eradication, which succeeded in 1980. With smallpox viewed as a likely bioweapon, Dr. Henderson said the lessons learned combating smallpox could play an integral role in the nation’s biodefense.

One of the prime biodefense challenges is that new bioweapons require little expense or biological expertise and can be quickly and easily developed using basic instructions available on Internet sites. Additionally, the release of a bioweapon is detected only after it has infected a population, often as patients enter emergency rooms. Characterizing such a bioweapon and then moving it through the process to obtain a vaccine or antibiotic is currently the “weakest link in the federal government’s response plan,” said Dr. Henderson. In his view, current countermeasures are slow to implement, inadequate to fight most bioweapons, usually not made domestically, and cannot be made on demand. There are few existing public-private partnerships in place to accomplish what is needed to be truly prepared, and the infrastructure doesn’t exist to support coordinated vaccine development and manufacturing on the scale necessary. “We have to be prepared to move through the process more quickly and effectively, and no one entity is set up to do that right now.

”UPMC has been at the forefront of 21CB since its inception, creating the blueprint for the vaccine facility. A year ago, UPMC President and CEO Jeffrey Romoff testified on the importance of the project before a U.S. Senate Appropriations subcommittee. The Pittsburgh-based healthcare nonprofit has also brought major international players to the consortium table, including Merck, Battelle, GE Healthcare and IBM. Each corporation would have a role in the proposed project.

Merck would bring experienced vaccine manufacturing guidance as well as research and development expertise. It would also establish best practices at the facility and cross-train employees.Battelle is the nation’s largest independent research and development institution, responsible for over $5 billion in research annually. Battelle would provide standards for product safety evaluation, support in creating infectious disease models, and advice on technology commercialization.

GE Healthcare works with groups worldwide to put vaccine, plasma, and insulin resources in place. It is a healthcare facilities planning consultant, premier supplier of laboratory equipment, and leader in process training for the biopharma industry.

IBM works with the majority of the world’s pharmaceutical companies, in addition to the three major U.S. prescription drug wholesalers. A leader in information technology solutions for research and development, regulatory compliance, manufacturing and supply- chain management, IBM would maintain the dynamic infrastructure to keep the manufacturing processes and operations running smoothly.

While IBM has participated in large joint ventures in other industries, General Manager of IBM Healthcare and Life Sciences Dan Pelino said the vaccine project is different: “This proposed public-private partnership with 21CB, its partners and the federal government is unique—the first of its kind.”