Nellie King is lying on a hospital bed, his once-sinewy muscles flaccid, his face ashen. The man who once hurled sinking fastballs past Frank Robinson and Ernie Banks is so weak from pneumonia that he can barely draw a breath. He has this terrifying sensation of his skin separating from his skeleton.

His youngest daughter, Amy, leans over his Mercy Hospital bed, and as he slides back into consciousness, she says, “Dad, it’s the bottom of the ninth inning. There are two outs. No one is warming up. It’s up to you.”

King laughs. Then in a stranger-than-fiction twist, he makes the biggest save of his life. He rallies not only for his daughter, but also to finish his new memoir, “Happiness is Like a Cur Dog,” and become one of the best Parkinson’s disease patients to ever wield a Wii remote control for bowling.

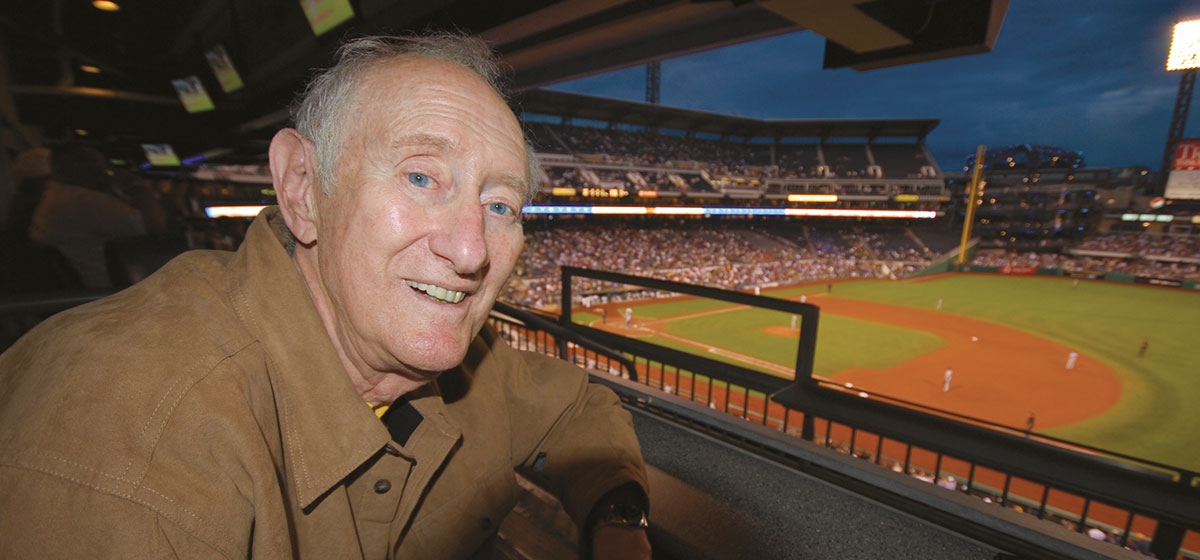

His recovery has led him to an unlikely athletic camaraderie inside Friendship Village of South Hills retirement community in Upper St. Clair. Far from the roar of Major League Baseball stadiums, King, 81, winds up. Only his long, thin right arm swings underhand before he flicks the Wii remote up toward the TV screen. The virtual bowling pins crash down, shattering the silence of the rose floral lounge. “Strike!” he calls out, as his left arm leans on his walker for balance.

Even with the tremors of Parkinson’s and severe back pain, the former relief pitcher and Pirates announcer understands the mechanics of an efficient swing. At 6′ 3″, down from 6′ 5″ during his athletic prime, King towers over his competitor—a slight man named George Hill, who also has Parkinson’s and uses a wheelchair. “Come on George,” he says. “Squeeze it and drop it.”

Hill misses and grimaces. King consoles him by saying, “You can’t get much hook on the ball when you are sitting down. The coordination is hard with Parkinson’s.” The next frame, Hill gets a strike and beams. “There you go,” King calls out. “We are the Parkinson pals.”

Hill, who trails 101 to King’s 150, quips that King is too scared to play Wii baseball with him. “I was never a good hitter,” King says, laughing. “That is why I was a pitcher.”

“Nellie has his own little ministry going on here,” says Cindy McClung, chaplain of Friendship Village. “He has a special touch with people. People find him comforting.”

King, who had his near-death experience two years ago, cheers up people like Hill, who moved from a spacious apartment in the independent living area of the retirement community to the health center after he suffered falls. His wife has Parkinson’s too.

King also consoles Jim Reynolds, whose mother,Virginia, is a resident of the health center because her advanced Parkinson’s has taken her ability to speak. Reynolds feels guilty traveling for his job, but King tells him. “You are doing everything you can. She is in a good place. The staff is watching over her. I am watching over her.”

For all of his wisdom, King is also like a kid, always looking for someone to play a pickup game. “He takes great pleasure in playing Wii, even if you win,” Reynolds says. “He doesn’t seem like someone who is 81 with Parkinson’s disease and living in a nursing home.”

The first time Reynolds met him, King was typing his memoirs at the computer in the lounge. Reynolds told him he was thrilled to meet the man whose voice was part of his cherished baseball memories in the ’60s and ’70s.

Reynolds loves hearing Nellie’s stories from his Pirates days. “He spins out one gem after another.”

Ask King about the title of his memoir, “Happiness is Like a Cur Dog,” and he will talk about Branch Rickey, the Dodgers’ general manager who broke the race barrier by signing Jackie Robinson before becoming general manager of the Pirates. A college-educated man who didn’t drink or carouse, Rickey would give his Pirate team talks that had nothing to do with baseball. “You can’t get up in the morning and say, ‘I am going to be happy today. You can’t will it,’” King recalls Rickey telling the players one spring morning. “Happiness is a byproduct of what you do with your life.”

Rickey then told the parable of a house painter who was haphazardly painting a garage door and a cur dog, or mutt, came near him. He tried to pet the dog, but the mutt ran away. It wasn’t until the painter became absorbed in painting, whistling and singing, that the dog came and sat by him, nuzzling his leg. “That is what happiness is like,” King says. “If you keep doing what you like in life, happiness is going to be by your leg all the time.”

King has lived his life that way, triumphing over a childhood that sounds Dickensian. He was born on March 15, 1928, in Weston Place, a tiny coal mining town in central Pennsylvania. The youngest of five, he was an accident; 17 years younger than the next child. When he was 5, his father, a coal miner, died, and his happy childhood came to a jarring end. It was the Great Depression, and his mother, left without a safety net, sent him at age 8 to the Hershey Industrial School, “an orphanage for poor Caucasian boys. It was crushing. I didn’t know anyone.”

He was put to work on a dairy farm, milking 30 head of Holstein cattle. “There was not much time for baseball,” he says. “Idleness was the devil’s workshop.”

But he knew he wanted to be a ballplayer, even though it was a long shot. At 18, he joined a YMCA league in Lebanon. A Cardinal scout saw him pitch, and liked that the lanky kid could throw strikes. He paid him $100 a month to play, but soon King was released. He persevered, once hitchhiking to a tryout. He may have never made it to the majors had he not gone to a farm team in Geneva, Ala. A fiery second baseman named “Cotton” Borsage watched him pitch and said, “Kid, you have great control. You throw over the plate consistently. You keep it down where the percentages are. But you don’t have any movement on your fastball. How do you hold the ball?”

“I hold it with two fingers across the seams like that,” he said. “I read in a book that is how Bob Feller holds it.”

“Look kid, you can’t throw as hard as Bob Feller. Why don’t you hold it with the seams?”

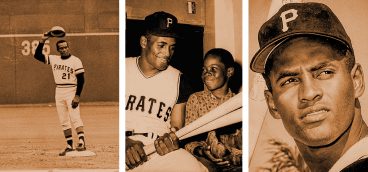

Putting his fingers along the seams helped him develop a mean sinking fastball, the edge that got him to the major leagues. In 1954, he signed with the Pirates. In four seasons there, from 1954 to 1957, he pitched 173 innings, winning seven games, losing five and saving six.

He loved baseball even if he only made $9,500 a year. “I was a baseball player in 1954 b.c.—Before Cash,” he quips. But his career ended abruptly at age 29, when he injured his arm throwing a curve ball.

With no idea what to do next, he began selling mutual funds. He was miserable. “I used to get on my hands and knees and pray that I could find something that would give me the same joy and satisfaction as baseball.”

King’s answer came the day he got a call from the Pirates’ front office, informing him that several small radio stations in Kittanning, Latrobe and Butler were looking for a sports broadcaster. He landed the job in 1960 and began his second act in broadcasting, doing a daily sports show and covering high school football and golf, which had a charismatic new star named Arnold Palmer.

In 1967, he got his big break. For the second time, he joined the Pirates, this time in the broadcast booth. King replaced Don Hoak and joined Bob Prince on the air. They had a rocky start.

King says he tried to play an obsequious role to the established Prince, but the star broadcaster resented him at first. “There was antipathy among professional announcers that these jock straps were coming in and getting into their game,” King says.

The tension came to a head in 1968 during a broadcast at Dodgers Stadium. Prince asked him a question about a long-haired catcher named Bill Sedakis, who needed to be revived with smelling salts after he slid into base. “What do you think of that? A young kid like that needing smelling salts,” Prince asked him on the air. When King didn’t reply, Prince said, “I asked you a question—aren’t you going to answer it?”

King fumed. That was it. He was either going to be fired or take a stand. “Don’t you ever show me up on the air again,” he told Prince during a break. “If you do that again, I will hit you in the mouth.”

From then on, they got on well, making a popular team until they were abruptly fired at the end of the 1975 season. (King tells the behind-the-scenes drama in his book.)

Once again, King was casting around for another job. He went to Duquesne University, where he became sports information director and golf coach. Even in his 70s, he was broadcasting and playing golf, shooting in the high 70s and low 80s.

Golf, like pitching, is all about balance. Parkinson’s disease has robbed him of his balance, and he is trying to keep his trademark optimism as his body fails him. “That is the tough thing about being old. You have to accept things that you can’t do anything about. It is more annoying than depressing. But I am not going to sit around and cry about it.”

Instead, King plays Wii bowling and delivers the 133 books he sold at Friendship Village. He walks slowly, inching along behind his walker, but his memory is racing.

“It was like a camera was running,” he says of writing his memoirs. “I could just replay my life. If you like what you are doing, memory soaks up everything around you.”

“Happiness is like a Cur Dog: The Thirty-year Journey of a Major League Pitcher and Broadcaster” can be ordered from Amazon.com.