Winter puts birders in a different mood. There are birds about, but they are fewer and generally more muted—focused on finding food, staying warm and getting through. The birds that stick around for a Pittsburgh winter are hardier, more committed, the stalwarts. They are the loyalists of cold.

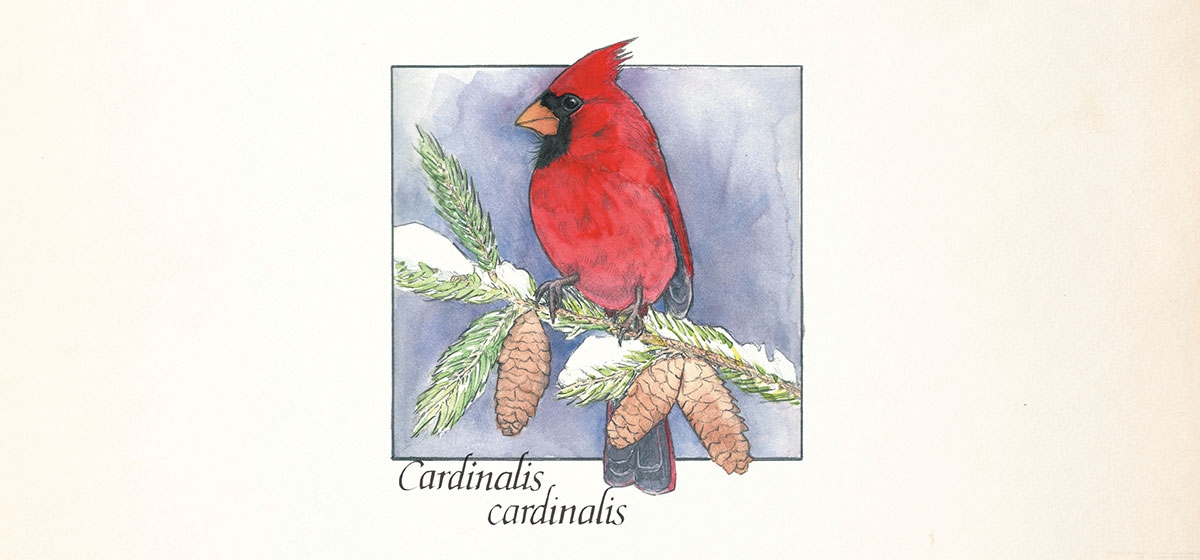

There is nothing better on a winter day than watching Northern Cardinals from my kitchen. I’ll brew a cup of tea, Red Zinger appropriately, and look out at the feeders that hang from a second-floor fire escape. Both birds and I are in the tree tops, and though the leaves have changed and fallen, I still feel closer to living nature as the birds come and go among dormant branches and gray light.The cardinals that I watch are likely Pittsburghers born and bred. Cardinals do not migrate and rarely stray more than a few miles from their natal precincts. Like many Pittsburghers, they know well enough to stay put. Everything they need is right here. In winter, cardinals use their strong, broad beaks as nut crackers, breaking into seeds to extract the meat with dexterous tongues. Human-provided kernels are all the better, for cardinals love feeding stations, saving time and energy on cold days as they forage less and feast more. Like all wintering birds, cardinals rely on fat stores to provide fuel for heat and fluffed feathers to trap warm pockets of air around their bodies. The splashy red and black of the males or the muted brown and red of the females is a welcome burst of color in a more subdued landscape.

Once there is more light and warmth returns, cardinals—both males and females—sing. They can be heard mostly in spring and summer but can vocalize year round. In breeding season, monogamous pairs can sing duets, sharing songs back and forth. This is unlike many songbird species, where the males are usually the vocalists. Once pairing happens, the females build twiggy, grassy nests in dense shrub. In fact, cardinals live in many diverse habitats, so as long as there is a thicket to rest in, the species will be found. Parents can muster through two or three broods of three or four eggs, so some 10 to 12 offspring a year are possible. Chicks are born reliant on parents, but it is only for little more than a week before baby birds fledge. If only human parents had it so easy!

Cardinals take their name from church officials of old whose red robes and hats marked their offices. The offices of our cardinals are no less holy in my estimation. I’ve noticed cardinals are the latest visitors to my feeders on a winter afternoon. I’ve wondered about that, why they are willing to risk predation at dusk for a few more mouthfuls of seed. I don’t think it’s gluttony, but instead a willingness to grace a darkening winter day with a bit of the feathered divine.

Feeding birds throughout the winter helps them get through our cold months. It has also encouraged birds like the cardinal to expand their ranges northward for more than 100 years. The Audubon Society of Western Pennsylvania sells high quality seed from their Beechwood Farms headquarters: aswp.org.