The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette has won five Pulitzer Prizes. It should have been six.

Editor’s Note: A former colleague and generally wonderful guy, Marino Parascenzo, has passed away at the age of 95. He was one of the nation’s best golf writers, having won the PGA’s Lifetime Achievement Award. He wrote a number of excellent stories for Pittsburgh Quarterly, but my favorite — and one of the best sports stories I’ve ever read — was “The Lost Pulitzer.” We’re re-publishing it again today for your reading pleasure and also as tribute to Marino. — Doug Heuck

The Post-Gazette won No. 5 in April for its coverage of the massacre at the Tree of Life Synagogue, but it should have won one 55 years ago for Morrie Berman’s photo of New York Giants quarterback Y.A. Tittle, beaten to his knees, dazed and bleeding, in a game against the Pittsburgh Steelers in 1964.

It’s generally regarded as the most famous sports photo in the world. The truth is, it’s a great photo that just happens to be about sports. It hangs in the Smithsonian. It hangs in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. And at the National Press Photographers Association headquarters at the University of Georgia journalism school, it hangs in a place of special honor with four other photos of epic moments in history—President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signing the declaration of war in 1941; Huey Long, the controversial Louisiana politician, making a campaign speech; the skeletal Hindenberg being consumed in a hellish inferno, and Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima.

How could a photo like this not win a Pulitzer?

Because the Post-Gazette didn’t run it. And how could any paper not publish a photo of this magnitude? There are various stories on that. This is the true story. First, about the man who shot it.

* * *

One would assume that Morrie Berman would have that Tittle photo displayed in his home in Pittsburgh’s South Hills. If so, I didn’t see it.

But Morrie, ever the photographer, did have a photo on display. It was mounted and had lights on it, and when you stepped through the front door, it stopped you dead in your tracks. No verdant valley or towering mountain, no frolicking grandkids. It might have been a kind of shrine, except it was a photo of a man and woman, bloodied, battered and clearly having died violently at someone’s merciless hand. And then someone had given them ironic repose, placing them together on the ground. The woman had been attractive. The man was bald, with stern features, what you could see of them. His entire head was grotesquely lumpy. Hell of an entrance. Spare me the encore.

“Looks like,” I said, finally, “Mussolini.”

“It is Mussolini,” Morrie said. “And his mistress.”

“Where did you find a shot like this?” I asked.

“I made it,” Morrie said.

It was late in April, 1945, in northern Italy, just ten days before the end of World War II in Europe, that Mussolini and his mistress, Clara Petacci, and a number of his fascist henchmen were hunkered down hiding in a Nazi road convoy, hoping to reach the Swiss border and sanctuary. They were captured by Italian partisans, shot, hauled away and dumped out at a gas station, and then strung up by the heels.

Morrie, an army photographer, was in the area, and he rushed off the instant he got wind of the capture. He arrived to find that Mussolini and Clara had been cut down and stretched out on the ground. He also found that the Italian folk had shown how they felt about their recent dictator, and had, among other things, beaten his entire head into a mushy pulp.

“You couldn’t recognize him,” Morrie said, “and so,” he added, moving his hands like a baker working dough, “I had to get down beside him and push his face back together, so that you could at least tell who he was.”

Morrie Berman knew a picture when he saw one.

Morris Berman, born in Wheeling, West Virginia, seemed destined to be a news photographer. He began his journalism career in 1928 at age 18, as a $15-a-week reporter in Wheeling. Itching for pictures for his feature stories, he bought himself a small camera because the paper didn’t have a photo department. Soon he was the photo department. Other reporters were asking him to shoot pictures for them. In 1937, he joined the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, an afternoon daily. Early on, they sent him out to cover a breaking story, first handing him a Speed Graphic, that 4X5 workhorse of a news camera. He was baffled. “I didn’t know anything about a Speed Graphic,” he said. When the Sun-Tele folded in 1960, Berman was among the survivors who ended up on the Post-Gazette.

* * *

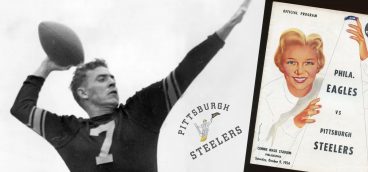

It was just the second game of the 1964 National Football League season, so neither team was yet as bad as it was going to be. The Pittsburgh Steelers were playing the New York Giants (both 0-1) that Sunday, Sept. 20, at the University of Pittsburgh’s Pitt Stadium. (The Steelers had also played at the Pittsburgh Pirates baseball stadium, Forbes Field. They finally had a home when they moved to the new Three Rivers Stadium in 1971.)

The Giants were leading, 14-0, in the second quarter, and had the ball deep in their own territory. Tittle dropped back and flipped a screen pass about the time Steeler defensive end John Baker, 6-foot-7 and 280 pounds, smashed him. The ball ended up in the hands of Steeler defensive tackle Chuck Hinton, who trotted in from eight yards out with the first of his two career interceptions and his only touchdown. The Steelers went on to win, 27-24, on their way to a 5-9 season. The Giants went 2-10-2.

If Morrie left any details on making the photo, I couldn’t find them. He was shooting a 35 mm that day, probably a Nikon F, standard at the Post-Gazette. He would have pre-set the camera, probably at 1/1000th of a second to stop the action, and with an aperture of f/5.6 for the best combination of depth of field for focus, and to account for the slightly overcast sky. The film was probably Kodak Tri-X.

Baker’s hit was so powerful that it lifted both of Tittle’s feet off the ground and knocked his helmet off. Tittle struggled to get up, and got as far as his knees. He knelt there, shoulders slumped, gazing nowhere vacantly, hands limp, blood seeping from his bald head. Morrie worked fast and cool. He got his shots before the trainers, coaches and others crammed into the scene. Tittle suffered a variety of injuries, most notably a concussion, and was done for the day. And, it developed, for his career. He would be 38 in a few days, and this was his 17th year in the league, the last of his brilliant, Hall of Fame career.

“That was the end of my dance,” Tittle was to say.

* * *

I was working the desk—not writing—that Sunday. I was one of the copy editors who did the final edits and wrote the headlines on stories as they rolled in. (This was the day of typewriters, paper and pencils). Dan McGibbeny, the No. 2 man in the sports department—every sportswriter should have a McGib to work for—was in the slot. The slot guy was in charge. He laid out the pages, picked out the photos, directed traffic to keep the stories moving. The system was chaos—beloved, maddening, addictive chaos—but it worked.

The stories were moving, but so was the clock, and McGib was getting edgy. The Steelers would lead the sports section, and he needed the photos before he could lay out the pages. Photos dictate layouts.

The photographers never had time for such luxuries as printing all their negatives on contact sheets for the editors to consider and discuss. They developed their film, printed their best stuff, got it off the dryer and hustled it out to the desk.

Morrie came up from behind me, carrying a fistful of 8X10 photos, still curled and hot off the dryer. He reached across me and put them in front of McGib. We all exchanged pleasantries, and Morrie turned and headed back to the photo lab. Nothing different here. And Morrie didn’t comment on any of the pictures. It was just another day’s work.

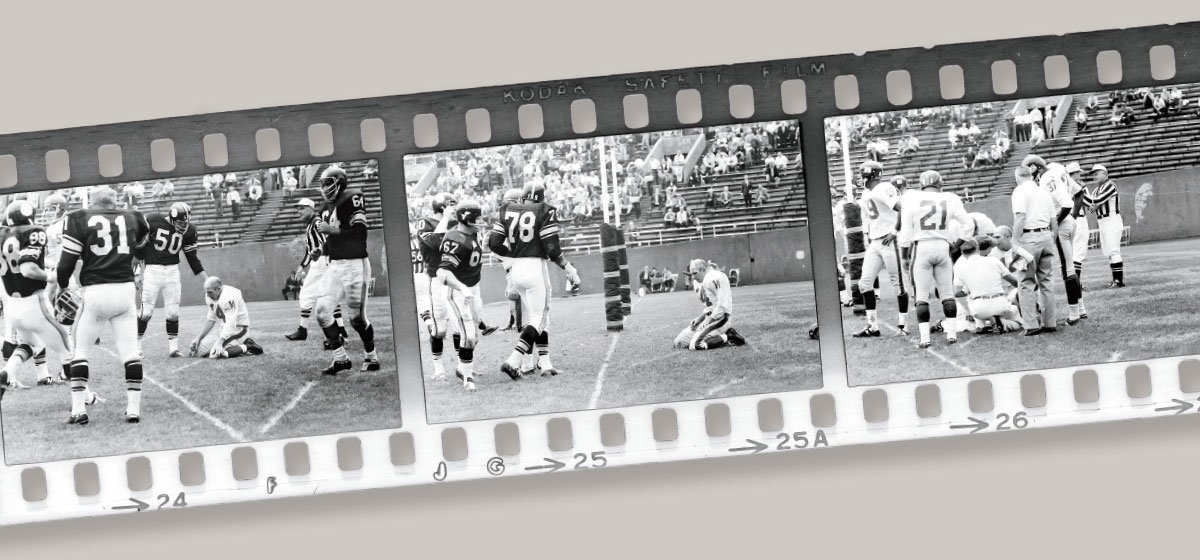

McGib shuffled through the photos and quickly made his selections. He had a natural. It’s not often you can tell a whole story in three photos, but McGib had a three-shot strip across the top of the page, under a banner headline. On the left, he’d have a three-column shot of Baker lunging into Tittle. On the right, another three-column, of Giant trainers and medics gathering around the fallen Tittle. McGib had two choices for the two-column shot in the middle—either Steeler linebacker Bill Saul standing beside the crumpled Tittle, reaching down as if to comfort him, or the other, with Tittle alone, slumped. They’d both have to be cropped to get down to two columns.

McGib slid the last two over to me. “What do you think?” he said. I knew he’d already made up his mind. He wasn’t looking for approval. But he knew I liked photography and he just wondered how I felt.

The linebacker shot was excellent, but the Tittle shot was stunning. If Michelangelo had carved it, it would have been the NFL’s Pieta. The power of the shot was in its suffocating pathos. The fallen knight, crushed, alone, bowed, helpless—the end.

“Wow,” I said, or something like that. “This one.”

“Me, too,” McGib said.

Sometimes an issue that has a course-changing impact and that reverberates for years actually came from a very simple thing that happened very simply. That was the case with Morrie Berman’s Y.A. Tittle picture.

What happened next was that Al Abrams, the Post-Gazette sports editor, wandered in. Abrams—and every sportswriter should have an Al Abrams for a boss—rarely came into the office on a Sunday. But he drifted in with a friend. He stopped on his way past the copy desk rim to chat with McGib about the section. What about pictures? McGib showed him his three-shot layout. Abrams liked it a lot. But he preferred the shot showing linebacker Bill Saul reaching for Tittle for the middle two-column.

McGib waved the fallen Tittle photo at him. “Hell of a picture,” McGib said, making one more try.

“Doesn’t show anything,” Abrams said. “Use the other one.”

And that was it. That was how Morrie’s Y.A. Tittle shot didn’t run in the Post-Gazette. There was no dramatic moment, no passionate debate over artistic merit, no nothing. It was just a difference of opinion, a simple judgment call, and the boss called loudest. McGib thought Abrams blew it, and so did I. A great picture had just gotten buried. We didn’t realize at that moment how truly great it was. And nobody was thinking about Pulitzers or any other prizes. It was just a day at the office. Even so, Berman would say later that Abrams’s decision had cost him a Pulitzer.

But the Post-Gaztte eventually did run the shot sometime later, along with the story that it had won the National Headliner Award. Not the Pulitzer, but the next thing to it.

Morrie Berman had won awards for his photography, but his Tittle photo was more than just a great shot. It has been credited with triggering a sea change in sports photography, showing that action wasn’t always necessary. That sometimes still life speaks louder.

Morrie Berman moved to Arizona after he retired and died there in 2002 at age 92. It was a final irony, then, that he became even more famous for not winning the Pulitzer.