My dad likes to reminisce, and after most of our 22 family members had moved to the living room after a holiday dinner to nap or watch sports, I learned how the desire for farm fresh eggs connected my parents to both the city of Pittsburgh and their rural roots in Tionesta, for their first four years of marriage.

In 1953 just after high school, Dad took a job with the Pennsylvania Highway Department Survey Corps. His supervisor was a mean, foul-mouthed guy, who threw a coworker against a bus and said he’d beat the – – – – out of him if he made another mistake. Dad knew he needed to find a different job where he could sign up for night courses and make a decent, pleasant living.

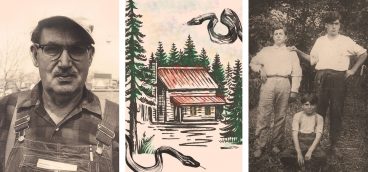

Tionesta, at the southwestern edge of the Allegheny National Forest, was and still is a rural community of small farmsteads. My mother’s family ran the McWilliams Dairy Farm there, and my relatives still farm that land. At 7, Dad took on farm work too. There’s a story about his driving a truck when he was so little he couldn’t see out of the front windshield while shifting. Dad’s family moved to the area for his sophomore year of high school. He was on the basketball team and Mom was a cheerleader at Tionesta High, graduating class of eight. They met and fell in love.

As he was yearning to leave the Highway Dept., Dad got a visit from his friend Carl Karlson, who suggested Dad apply for a job at the Westinghouse Electric plant in Pittsburgh where he worked. The plant was a sturdy brick building on Penn Avenue between Point Breeze and Wilkinsburg, across the street from the (still there, still excellent) Evergreen Cafe.

Dad made the trek into the city like so many other men at the time. As he put it, “That next Monday I drove to Pittsburgh, walked into the Westinghouse plant, and asked the personnel manager, Logan Roan, for any job that would allow me to enroll in a night school program. Roan said I could start as a core winder the next week at a salary of $156 per month.”

Dad moved to Pittsburgh, living temporarily with Carl Karlson and his school teacher sister. My parents had gotten engaged at their senior prom, and after they married that November, they rented their first apartment in Wilkinsburg along with Dad’s twin sister Doris, two hours from their families. Both Doris and my mother found secretarial jobs at Rockwell Manufacturing, and they split the $50-a-month rent three ways. “We ate lots of Spam, potatoes, and things we could bring back from the farm. We did quite well,” Dad noted, “and were able to save some money.”

Both the Flick and McWilliams clans are large—nine siblings among the Flicks and 12 in the McWilliamses. Every weekend my parents drove back to Tionesta to have supper at the McWilliamses’ on Friday and Saturday, and then Sunday lunch at the Flicks.’ Grandma Flick cultivated a huge, beautiful hillside garden and was an obsessive canner, pickler, quilter, and rug hooker. I still remember the taste of her unsweetened concord grape juice and her sweet-and- sour pickle relish, always served in a cut glass bowl. Mom hung out with her sisters—Edna, Lois, and Arlene—playing cards. Dad hunted and fished with my uncles Jake, Harry, and Ralph. Mom’s sisters made the same weekly weekend trek in from Erie with their husbands and children in tow. They all checked in at the McWilliams farm upon arrival. “I don’t know how Grandma and Grandpa McWilliams put up with us,” Dad said, “but they would be upset if we didn’t come home.”

By 1955, Dad’s salary was up to $250 a month, my brother Dan was born, and they moved into a bigger apartment. Doris moved back to Tionesta to marry Jim Tucker. “Somewhere in the process, our Pittsburgh friends knew we were going to the farm in Tionesta every weekend,” Dad said. “I told them Shirley’s brother had a chicken farm, and I had access to good fresh eggs. At first I would bring back a few dozen as a favor for a few friends. Then the word got around that I could bring back fresh eggs at a good price.” Since my parents had some difficulty paying the 25 cents a gallon for gasoline, Dad determined they could subsidize their weekend trips if he charged people 10 cents more than he paid for the eggs. And so the egg route was born.

Dad picked up the eggs in Tionesta each weekend and delivered them at the plant Monday morning before work. Westinghouse then moved into a four-story plant in East Liberty, radically upping potential egg sales, and the egg route exploded to 100 dozen per week. “Management, security officers, secretaries, people from all parts of the plant were my customers,” Dad said. For me, nothing brings together the idea of post-World War II America more than my young, optimistic father walking into the plant’s stark industrial rooms filled with wires and buzzing electronic progress, carrying trays of freshly laid eggs.

Ralph, my Mom’s oldest brother, a gentleman farmer, kept the chicken coop. He gathered the eggs each day, brought them to the springhouse, and put them through an egg washer. “The grain and various chicken feed had a good smell,” Dad recalled. “The spring house was cluttered with egg baskets, egg boxes, and various milk separator parts and binder twine.” Ralph made dandelion wine each year and stored it in the springhouse to keep it cool. “He would offer me a drink from time to time,” Dad said. “It was real smooth.”

Dad rigged a candling device, checking each egg for the blood spots that his urban customers didn’t like. The double-yolk eggs were extremely popular. “They loved them.” At the peak of his egg business, he had to visit three to four farms to fill his orders. He made some good friends with local farmers in Redbrush—the Alexanders, Korbs, and Wagners. “When I would go to the Korbs for eggs during the middle of the winter, she would give me some fresh apples that they kept in their springhouse.” Keep in mind that from December 1954 to June 1957 my brother Danny was in the car with them, the eggs, suitcases, and the bags of canned goods and garden produce from Grandma Flick.

They traveled to Tionesta on Route 8 through Oil City, no highways yet existing. “Pittsburgh was still a smoky city, and you would have soot on your car and house a lot,” Dad said. “The houses we lived in had coal furnaces. You would notice the clear air and quiet nights when we were in Forest or Clarion county. Our favorite stop each trip was the ice cream store in Harrisville.” Hughes, open since 1928 and still there on Harrisville’s Main Street, serves Penn-Gold Ice Cream.

By this time, Dad had inched up another notch in the long Westinghouse ladder to a position working directly with the engineers, making $300 a month. “They were pleased that I was going to night school four nights per week. When I had some spare time I would do my homework, and they would help me with any math or science questions.” Most of Dad’s fellow employees were from Pittsburgh, and a country boy was a novelty. A friendly and curious guy, Dad made a lot of friends.

Yet by July 1957, he faced a hard decision. He wanted to become an engineer, but he needed to make more money than Westinghouse could offer him with his skills. Though he’d earned an academic scholarship that year, my parents decided to move to Koppel and then Beaver Falls, where Dad trained to sell life insurance. With this move, the egg route ended, and I imagine my father’s customers went back to buying regular, boring eggs at their local supermarket.

My parents settled in Beaver Falls and live there today. They purchased Uncle Ralph’s farm in 1987, making a big circle in this egg story, and it is now a weekend retreat for my family, and where I got married 19 years ago. The chicken coop is gone, although you can trace the outline of its stone foundation. The springhouse remains the water source for the farmhouse, and Dad said that when they bought the farm there were still a few jugs of dandelion wine in there. He was tempted, but decided it was best to dump them out.

These days when I visit and walk out into the farmyard to inhale the wonderful silky night and zillions of glittering stars, I think about how hard it must have been some Sundays to pack up that car and head back into the city, slag heaps aglow.