The Day Women Took Over

Editor’s note: This year, as the nation celebrates the centennial of the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution—ushering in women’s suffrage—Pittsburgh is claiming its own piece of the story through the Pittsburgh Suffrage Centennial. Learn more at www.pghsuffrage100.com.

It was a hundred years ago this year that the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution became the law of the land and ushered in federal support for women’s suffrage:

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

It was the culmination of an 80-year battle for the ballot that had been formally launched at a women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, N.Y., in 1848. And because the Constitution leaves voting rights to the states to grant and to administer, the battle had been waged at the state as well as the federal level. As a result, some states, all of them in the West, granted votes for women decades before the 19th Amendment was passed. Pennsylvanians continued to pursue a state constitutional amendment right up until the federal amendment was passed in 1919 and ratified by the states in 1920. Even then, women were not guaranteed the ballot. They just could not be denied it simply on the basis of sex.

The Pennsylvania campaign for women’s suffrage went on for more than a decade with Pittsburgh playing a “pivotal” role according to the The New York Times in 1915. Here, suffragists of the Equal Franchise Federation devised a spectacular series of strategies—from pulpits to parades, from schoolhouses to Kennywood, from exclusive clubs to factory gates and union halls, from car shows to poultry shows, from the Opera House to Forbes Field and the Ringling Brothers Circus, from bustling city street corners to dusty country roads.

So it was that at 8 a.m. on a fair February morning in 1912, 16 women filed into the offices of the Pittsburgh Sun at the corner of Wood Street and Liberty Avenue, dressed in long, slim, tailored suits and broad-brimmed, deep-crowned hats. With a couple exceptions, these women were not seasoned journalists. They were club and society women, debutantes, professional women and housewives. But each went straight to a desk in the newsroom, sat down, and went to work.

It was Leap Day, February 29, a day recognized as a time to turn the tables on traditional gender norms. In Irish tradition, it was known as Ladies’ Privilege or Bachelor’s Day—the one day when it was considered acceptable for a woman to propose marriage to a man. In Pittsburgh, as the women’s suffrage movement was gaining momentum, it was a day for a cast of female characters to assume editorial leadership of the city’s evening newspaper for one very special issue.

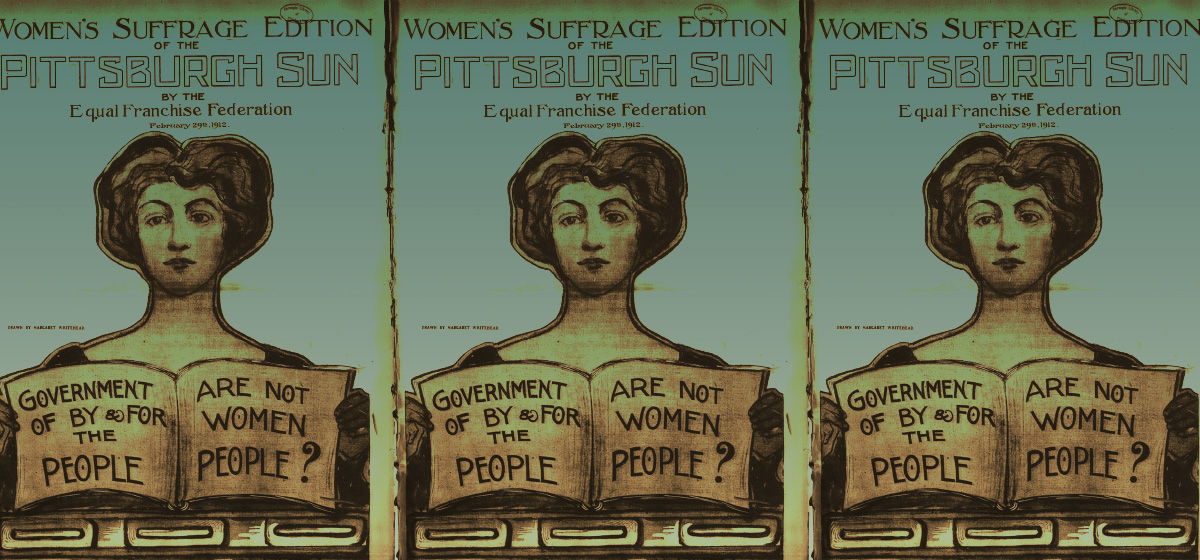

The Sun’s management was sympathetic to the cause and offered the suffragists full control of the February 29 edition. Advance advertising promised “Something New Under the Sun for Women by Women! Once-in-Four-Years! …SO NOVEL, SO REMARKABLE IN ITS NATURE that it will mark an epoch in newspaper history, not alone of Pittsburgh, but of the United States.” The ad admitted, “An Innovation is a Gamble.” But newspapermen across the country watched with keen interest and placed advance orders for their copies of the “Women’s Suffrage Edition.” It was a unique moment in journalistic history.

The women had previously observed the operation, so they knew what to do. As the interlopers took their places, the regular staff watched with trepidation and wondered what, exactly, these guest editors would ask of them. They were only women, after all. But they were formidable women, all of them ardent members of the Equal Franchise Federation of Western Pennsylvania.

Euphemia Bakewell, a regular contributor to the Pittsburgh Daily Post, sat at the managing editor’s desk. Her sister, Mary Bakewell, president of the Equal Franchise Federation, was the editorial writer and contributed several poems and limericks. Jennie Bradley Roessing, who would go on to conceive of a winning strategy for selling the suffrage cause statewide, served as city editor. Lucy Kennedy Miller, who would become head of both the local and the state suffrage organizations and widely feared among corrupt politicians, assumed the role of assistant city editor.

Other women served as music, art, and drama critics and took charge of publicity, circulation, telegraph news and the society and school pages.

Dozens more served as contributors from afar. Among them was Anna Howard Shaw, a physician, Methodist minister, and head of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, who called the band of 16 “a splendid enthusiastic lot” who “ought to succeed in stirring things up.” The editors sought the opinions of local politicians, businessmen, attorneys, doctors and clergy. Cables and telegrams poured in from leaders and lawmakers in every corner of the world with messages of support and congratulations for the Sun’s journalistic triumph. With such a diversity of supportive voices, the paper represented the most comprehensive and effective suffrage propaganda piece produced to date anywhere in the country.

“From the first page to last page it was a paper of, by and for women,” The Pittsburgh Post reported. They wrote news stories, editorials and critical reviews. They conducted interviews. And they showcased the accomplishments of women in art, music and drama alongside celebrity endorsements from the leading ladies of the day. One news item welcomed the first Colored Women’s Equal Franchise League of Pittsburgh to the struggle, headed by Mrs. Israel S. Lee. Suffrage news from abroad cited progress in more than 20 countries.

Even the sporting editor was booted for the day, as Miss Emily McCreery focused on female athletes. A half-column was devoted to world champion baseball star Miss Myrtle Rowe, who happened to come from New Kensington. Another story profiled Miss Cora Livingston, champion wrestler. A survey of local girls’ basketball teams pointed out that basketball promotes strong healthy bodies, which, as one reporter noted the next day, “and these strong healthy bodies will maintain intelligent virile brains fit to decide the burning issues of the day at the polls.” And the usually reticent captain of the Pittsburgh Pirates, Fred Clarke, provided pro-suffrage quotes.

The collective voices of endorsement cited numerous problems that women could address more effectively with access to the voting booth: impure food and water, excessively young ages of consent, child labor, white slavery, poor working conditions for women, vice, war, unsanitary tenement conditions, inefficient schools and more.

They invited an article from The Pittsburg Association Opposed to Women’s Suffrage, but the newly formed adversary declined. For this one day, their arguments would not be heard—that women belonged in the home, that politics would destroy the feminine qualities in women, that women’s views were already adequately represented by their menfolk, and that states where women already had the vote had not been improved by it.

The paper was not lacking in humor. On the front page, one of the lead stories carried the byline of “A Mere Man” and related the experience of working for a female taskmaster. “The most striking thing about suffragists when they publish a newspaper,” wrote the author, “is that they do not remove their hats when they begin to work. This shows that they have good nerves. Their concentration is splendid. The fact that they could wade through the mass of news matter which develops during the course of a day, with plumes waving about their heads sometimes obstructing their vision, without their nervous temperament putting on a three-act show, is beyond man’s understanding. But they did it.”

When it came time to print, it was Euphemia Bakewell who went down to the pressroom, a union stronghold. There she found waiting for her a card of membership in the International Printing and Pressmen and Assistants’ Union of North America: “This is to certify that Miss Euphemia Bakewell is entitled to work in the pressroom of The Pittsburgh Sun and is entitled to all union privileges for this one day. W. J. Smith, Secretary.” With that validation, Euphemia threw the hefty lever that set the spinning rolls and whirring wheels in motion. And as the first damp paper came off the presses, she took hold of it triumphantly.

It then fell to the women to get the paper out to readers. In limousines and on foot, thousands of women armed with bundles of newspapers took to the streets, which grew more crowded as the word spread. The papers quickly sold for one cent each. The “suffrage newsies” even enlisted the help of the alluring celebrity mystic, Anna Eva Fay, who peddled papers from an automobile in between her performances at the Grand Opera House. Groups gathered—on the streets, in cars and trains, theaters and shops, in homes—to discuss the contents of the unprecedented paper. Lucy Kennedy Miller declared this first suffrage issue of any paper to be “a coup for both the suffrage organization and the Pittsburgh Sun.” The paper contained more local advertising than any other Pittsburgh paper that day, and its circulation was the highest in the Sun’s history.

The suffragists expected that the paper might have even greater impact on women than on men. “We find it easier to convert men than women,” Euphemia Bakewell explained. “That may seem strange, but it is easily explained. The man is used to politics, and is awake to the progress of the times. He can grasp political situations easily, and when they are brought to his notice, he can easily adapt himself to them. With the woman, who has hitherto had no experience in politics and who has not followed politics, all this is too new to her. Therefore, we are so confident with our newspaper venture. We know that the reading of the Thursday Sun will not only hold the interest of women but will confirm the vagrant views of some men, convert others, and make enthusiastic supporters of many.”

The same week as the special edition of the Sun, the Pittsburgh papers reported on the militant activities of the suffragettes in England, who had smashed plate glass windows of large department stores, government buildings and private clubs in London as a protest demonstration. Led by the infamous Emmaline Pankhurst, 120 women were arrested and sentenced to two months in prison. The Pittsburgh suffragists must have taken some pleasure in knowing that their peaceful but persuasive approach garnered more positive public attention than did the militant activities of their English sisters. Still, it would be another eight arduous years—a roller coaster ride of buoyed hopes and dashing disappointments—before women in the United States would secure the vote through the 19th amendment to the Constitution. That battle would employ the power of the press as just one of many ingenious tactics in a large and diversified arsenal.