Pittsburgh has produced some renowned birders and ornithologists. Our hills and rivers attract a wide variety of birds, and they, in turn, inspire generation after generation to look to the skies—from John James Audubon, who painted the long-extinct Passenger Pigeon while passing through the Gateway to the West (an old moniker for our fair city), to Clyde Todd, curator of birds at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History for the first half of the 20th century, to living legends Ted Floyd of the American Birding Association, Jack Solomon of the Three Rivers Birding Club, Bob Mulvihill of the National Aviary, and Bob Leberman, Bird bander emeritus at the Powdermill Avian Research Center.

I was lucky to take a spring bird walk with Dr. Scott K. Robinson, a son of Pittsburgh and now a curator at the Florida Museum. He began birding as a student at Shady Side Academy in Fox Chapel, and that’s where we were walking that day. Robinson had a keen ear, vital for any serious birder, and he focused my students and me on a high, thin whistle I had never noticed. None of us could see the bird, but we separated the notes from the rest of the spring cacophony. “Cedar Waxwings,” he noted. Subtle, beautiful, almost missed.

Cedar Waxwings spend time in shrubs, high and low, and in trees of any species, not just cedars, though they love any fruit-bearing trees. (It’s their appetite for cedar berries that gives them their name.) Primarily frugivores who also take insects on the wing in times of plenty, they’re truly gorgeous birds. I’ve seen flocks of waxwings feasting on the fruits of dogwoods and viburnum, gleaning in summer and winter. (Too many overripe, fermenting berries actually can cause intoxication or worse, a hazard of their specialized diet.)

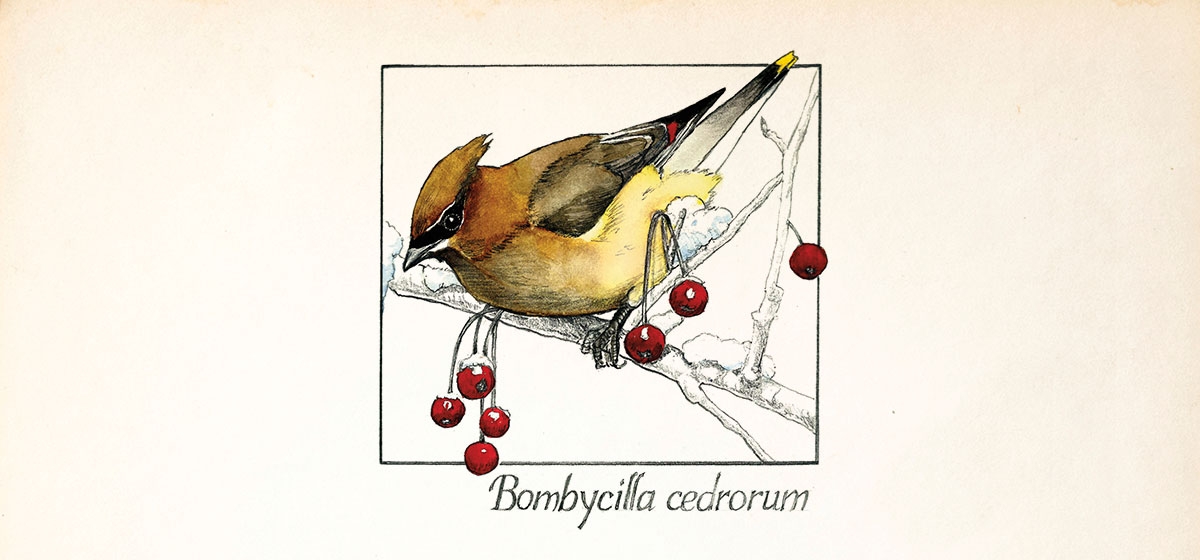

Waxwings wear dashing black masks. Topside feathers are cinnamon-brown from swept crest to midway down their backs, then slate gray from there to the bright yellow, sometimes orange, tips of their tails. (Orange can result from feeding on honeysuckle berries; I’ve seen this at Powdermill.) Their undersides shift from brown to a pale yellow. And then there are the wings, brown to gray with what appear to be red waxy droplets on the ends. Actually these droplets are flattened feather shafts that take their color from a carotenoid pigment, and they signal a bird’s age and sexual maturity. Birds mate with partners that have similar droplet quantity and quality.

Weighing in at an ounce, with a body about six inches long and a 10-inch wingspan, waxwings are in our region year-round. They breed into Canada and winter as far as Central America, but happily for us, small flocks are almost always around. Females are the nest builders, choosing a spot in a tree three feet off the ground or higher. Sometimes, they nest in neighborhoods, a dozen or so brooding pairs.

Because of their proclivity for fruiting ornamental trees and the proximity of those trees to buildings, waxwings can be susceptible to window strikes. I picked the silky body of one up outside my school last year, sad to cradle in my hands that remarkable, pure creature.