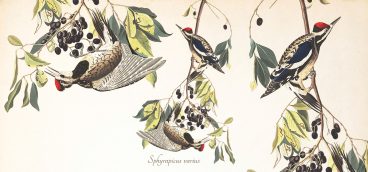

The male is dark blue, white and black. The female is olive brown and grey with a white patch mid-wing, when folded. The contrast is called sexual dimorphism — two versions of the same species depending on gender. Look and listen for something spectacular. This is a bird you’ll want to find.

My first encounter with the species was at the beginning of my teaching career. At Chewonki’s Maine Coast Semester, students were quizzed every week on local birds. They reviewed recordings and then went outside. “I am so lazzzy,” sang the male black-throated blue, which rarely applied to students there. “Beer, beer, beer, beeee” was another version, clearly for graduates. The mnemonics were catchy and made the spring and early summer full of memorable phrases that anchored the birdsong in human language, even if briefly.

My next visit with the black-throated blue occurred nearly a decade later. I joined students from the University of Vermont who were conducting serious science in the Green Mountains, banding males of the species to assess population dynamics. I remember one mosquito-filled hike through the woods with a portable mist net, audio speakers, and a Christmas tree ornament made up to impersonate a rival male. Net set, decoy deployed, we played the song (definitely the graduate version after fighting away the bugs), and within a minute we had the bird. A tiny metal band was looped around the male’s leg, the wing measured, blood drawn, and the confused guy was set free, quickly shaking off the encounter and defending his breeding territory once again.

In Pittsburgh, my favorite place to encounter the black-throated blue is along the Meadow View trail at the Audubon Society’s Beechwood Farms. There, I’ve watched males foraging low, gleaning spring spiders and insects. Likely, they were just passing through to higher elevation forest interiors, their preferred breeding grounds. They don’t nest in the fragmented sprawl typical to Pittsburgh. We’re flyover territory for them.

This summer, when populations are at their peak, males will bring back buggy meals to cup-shaped nests near the ground and brooding mothers whose bodies warm eggs for nearly two weeks before the chicks hatch. Then it’s a feeding frenzy for a week to 10 days as the featherless babies gorge themselves, fast forwarding from blind newborns to airborne juveniles.

They take to the wing by instinct, muscles developing just as evolution intended, the fledglings coaxed from the nest by encouraging parents. Before migration, some 150,000 males of the species might be counted in the commonwealth. Many will perish during the rigors of fall migration, over the cold months, or returning from wintering grounds in the Yucatan, Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and nearby regions. That makes hearing or seeing the black-throated blue warbler all the more exciting during these sunny months.

Whether in the lazy days of summer sipping a cold beverage at home, or exploring new places when COVID rules allow, may this warbler share its beauty with you.

Share your avian encounters, photos or questions at PQonthewing@gmail.com.