The Beauty of Commitment

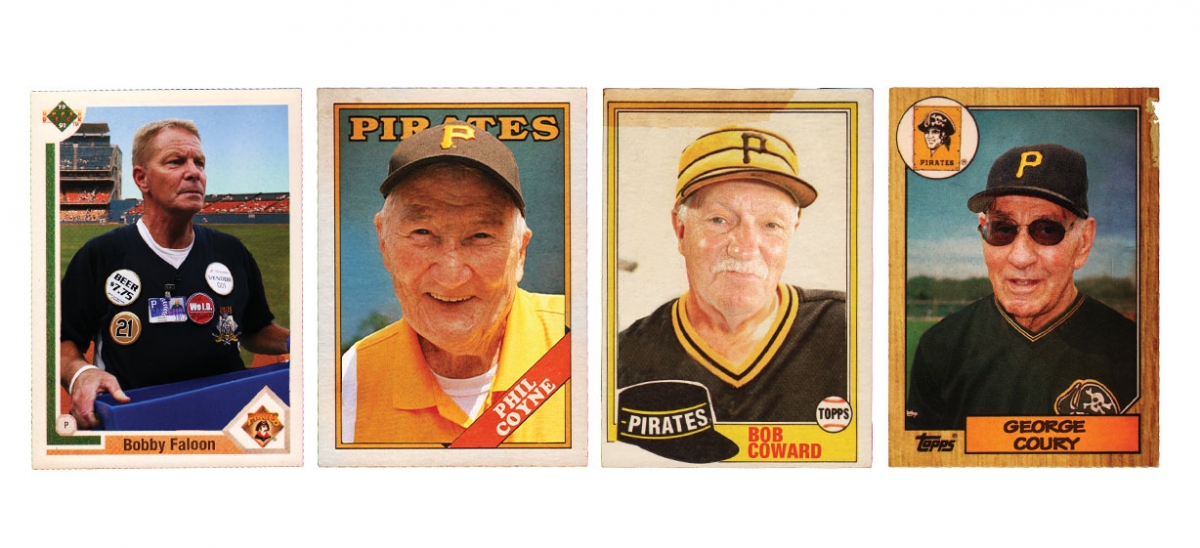

Bob Coward, dog-eared scorebook in hand, hurries through the turnstile at PNC Park for what will be his 2,600th-and-something Pittsburgh Pirates home game. A compact man who once worked as a prison guard at Western Penitentiary (now SCI Pittsburgh) on the city’s North Side, Coward darts through the thickening crowd, greeting ushers and vendors as he makes his way to his seat.

Within the confines of the park, he is Baseball Bob, a familiar figure in denim shorts, Pirates T-shirt (a Free-shirt Fridays freebie), Pirates cap, white socks and black sneakers.

“We’re all die-hards in this section,” says Coward, as he settles into a club-level seat beneath the overhang in section 210. “There are no casual fans here.”

Attending 81 home games a year is no small feat, but Coward had racked up years of perfect attendance until 2007, when he got stuck between floors in an elevator in his apartment building. “I was on my way to the game,” he recalls. “By the time they got me out of there, the game was in the seventh inning.” He got back on track, but a couple of years later, an appendicitis attack further tainted his record. Still, he has seen more major league games than most fans.

A bachelor, he has shaped his life around baseball, switching from guard to mailroom duty at the prison so he could have weekends and evenings free for games, and moving to a Downtown high-rise so he could quickly get to the park.

Distance is a non-issue for super fan George A. Coury Jr., who has attended more than 3,500 Pirates home games over the past 54 years, despite living an hour away in Homer City. Now 77 and still working as a public accountant, Coury saw his first major league game in 1947—the year Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Coury has missed just 19 games since, for the funerals of his parents and wife, assorted high school and college graduations, a couple of family vacations that couldn’t be postponed, a broken leg and his daughter’s wedding, although he spent most of the reception in the hotel bar watching the Pirates on TV. Even a blown transmission failed to keep him from seeing the Bucs do battle at Three Rivers Stadium, he admits.

“I had the car towed to a garage, and then I had a friend pick me up and take me to the park,” says Coury, who has had season tickets since 1970, the year Forbes Field closed and the Pirates moved to Three Rivers.

His seats are on the first-base line at PNC Park. The Buccos’ 20 years of consecutive losing seasons—a record in major league baseball history—have failed to foul Coury’s passion for the Great American Pastime.

“There’s no such thing as a bad baseball game as far as I’m concerned,” Coury says. “I’m a baseball fan first and a Pirates fan second. I come because I love the game. ” And he isn’t alone.

Phillip Coyne, 94, has him beat by more than 1,000 games, having ushered for the Pirates every year since 1936. His day job was in a machine shop. His heart was at Forbes Field. Back then, a ticket to the bleachers was 50 cents, a hot dog and pop cost less than a buck, and fans could enjoy cigarettes and cigars in their seats, he says. “All the men wore straw hats to the games and gathered in section 15 behind home plate to talk and smoke.”

Although there were “kids’ days” back then, fewer children came to games, Coyne recalls, and the atmosphere at the park would today be a purist’s dream.

There was no hyper-stimulating Jumbotron—an affront to the pastoral nature of a sport in which downtime is part of the rhythm of the game.

“A man hung the score in the outfield after each inning,” recalls Coyne, who could walk to Forbes Field from the Oakland home he still occupies today. After the games, players would take streetcars to East Liberty and Swissvale, riding alongside fans.

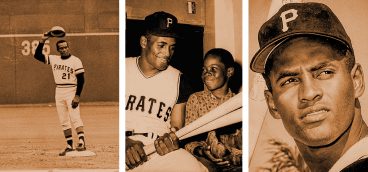

Bobby Faloon joined the Teamsters union to become a Pirates vendor when he was just 13, and remembers a familial culture in the days before free agency, that included even star players such as Roberto Clemente.

“I’d walk to Forbes Field from Lawrenceville—about three or four miles—for every game,” says Faloon, now 59, living in Dormont, and still hawking beer at PNC Park. “If Clemente happened to drive by, he’d have his driver stop and pick me up. He took care of me. He’d tell me to be a good kid.”

Players played every day, and some of the most revered spent their entire careers with one team. Willie Stargell was a Pirate for 21 years. “Players today are businessmen; they’re more aloof,” says Coward. “They didn’t used to make much more than the average person. Now, even average players make millions of dollars.” Owners, too, have turned baseball into big business, he says. “Team owners used to be philanthropists. They had teams because they loved the sport. They didn’t care if they made money. Today, it’s all about the money.”

Coward has kept the scorecard from almost every game he has attended, but needs little prompting to recall in detail hundreds of wins and losses he has seen. Game five of the Pirates’ 1972 championship series against the Cincinnati Reds caused a heartbreak that still pains him today.

“Steve Blass pitched eight innings and held the Reds to two runs; then Bill Virdon decided to bring in Dave Giusti to pitch to Johnny Bench in the ninth. Bench hit a homer to tie the game. The Reds loaded the bases. Moose came in and threw a wild pitch to let the winning run score. That loss devastated me,” Coward says. “That same year, on New Year’s Eve, Clemente was killed in a plane crash.”

Cable TV makes it easy to follow baseball today, but folks who rely on ESPN highlights miss the magic of a sport in which length of games and length of season require an abiding commitment—a kind of settling in. “If I take people to a game, I say we’re staying no matter when it ends,” says Coury. “I remember a twi-night double header with San Francisco (at Three Rivers). One game went 16 innings and the other went 15, and there were rain delays on top of that. There were 48,500 people in the park at the beginning of the night and 200 people at the end. My friends were P-O’d with me because I wouldn’t leave. We didn’t get home until 4 a.m.”

It takes another fan to understand, says Robert Green, a physician from Upper St. Clair, who is himself a PNC Park regular. “If you didn’t grow up with baseball, you might not get it. But if you did grow up with it, baseball’s in your blood, and there’s no point in overthinking why you love it.”