The Art of Taxidermy

The Victorian Era is known for its décor, literature and scientific developments. However, alongside the works of Dickens and the birth of photography, a long-dead style of art re-emerged in Victorian homes: taxidermic animals.

That art originally began as a way for scientists to showcase an animal’s biological features and was used by ancient Egyptians who buried embalmed creatures alongside mummified bodies. Crude versions of taxidermy re-emerged in the Middle Ages, and specimens were stuffed with cloth by upholsterers during the 19th century. English ornithologist John Hancock modernized taxidermy during the Victorian era, mounting birds he had hunted and displaying them at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Viewers were in awe of the lifelike appearances. Now, in the U.S. taxidermy schools exist in every state to certify would-be natural artists.

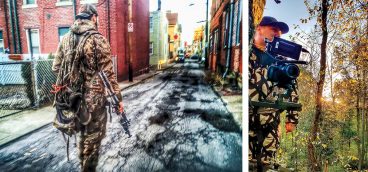

“When I was a young boy, 11 or 12 years old, I liked to hunt and fish,” said Ralph Sherdner, owner of Sherdner’s Taxidermy in Butler. “When I started hunting, I wanted to save things. It would drive my Mom crazy when I’d tack these [animals] up on the walls. They were mementos of hunting with my Dad. I couldn’t always afford to pay to have it all done so I learned the basics and did it as a hobby for years.”

Sherdner learned under Joe Meder, a world-renowned taxidermist and has been plying his trade since 1988. “The taxidermy industry is very healthy; there’s a good market. In 30 years, I’ve never run out of things to do. It’s a well-kept secret.”

A full-shoulder deer mount typically costs over $500, with extra charges for bucks and poses with open mouths. Life size mounts can cost thousands, depending on the animal being mounted.

Taxidermy comes in several forms, but the “conventional” method is what taxidermists typically perform. Conventional taxidermy always uses the animal’s real skin. Taxidermists remove the skin, tan it and mount it over a mannequin. These forms are either made from wool and wire or polyurethane.

“Sometimes, animals are freeze dried,” Sherdner said, calling that the second most popular option. “That’s not really taxidermy—just positioning the animal and then drying it out.”

The animal’s eyes are replaced with artificial orbs made of glass, clay or wood. Sometimes, taxidermists design and make these themselves, while others order them in bulk from wholesalers.

The third most popular method of taxidermy is reproduction, a type often used on fish. Detailed measurements and photos are taken of the animal, and the taxidermist mimics its appearance on a sculpture made of fiberglass or resin.

Each taxidermist has his own style, from the materials he uses in the form to the way he interprets the animal’s poses. For many, including Sherdner, deer provide the mainstay of the business.

“Deer are my favorite for commercialism,” he said. “But my personal favorites are birds such as grouse or pheasants. They are where my heart is at as a taxidermist—it’s the truest form of it.”