Fall is a time of movement: college students packed in SUVs returning to classes, younger kids nervous to get back to school, the lazy days of summer fading fast. Millions of birds are moving, too, some passing through the Pittsburgh area en route to wintering grounds to the south.

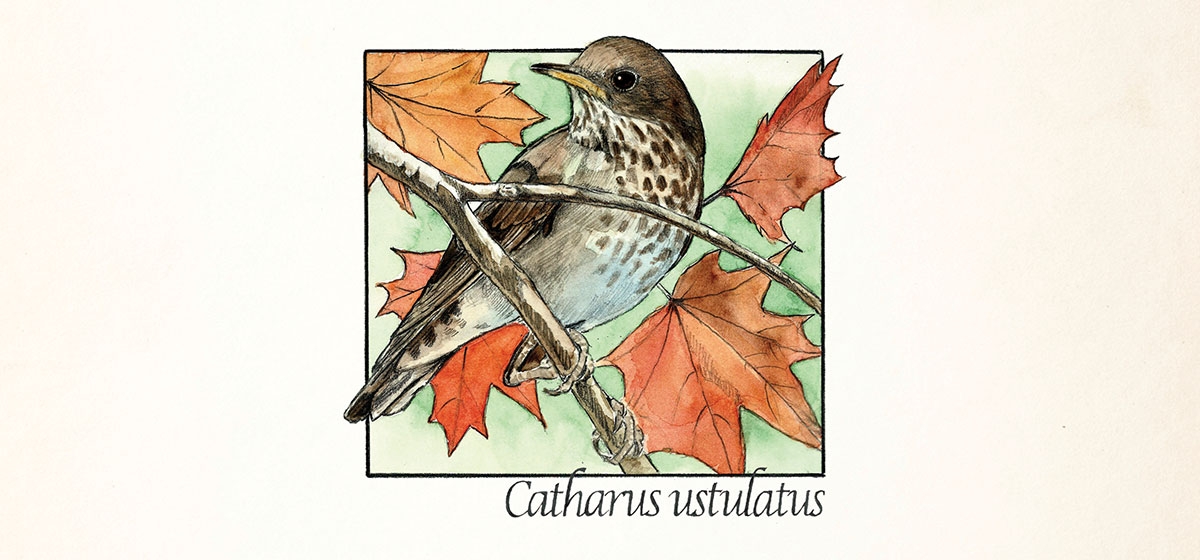

Some of these migrants are more heard than seen, including the Swainson’s Thrush, a champion longdistance migrant that flies over western Pennsylvania each fall and spring. Thrushes include the Hermit Thrush, quite common in our area, and the Wood Thrush, both beautiful singers; the Greycheeked Thrush and Veery; and the familiar American Robin and Eastern Bluebird, all members of the same scientific family. (Remember what you learned in biology class: kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, species.) The Swainson’s Thrush may win the awards for least seen and hardiest traveler.This medium, robin-size brown bird with speckled throat and chest prefers the forest, but can be found in many habitats. It often forages for insects and small crunchy critters, including ants, in the shadows of branches or on woodland floors, but it also can be seen munching berries and fruits in the summer. Moving between Alaska and Argentina and ranging from the East Coast to the West, these ounce-and-a-half birds have extraordinary endurance, pushing north past Pittsburgh to breed in the coniferous forests of northern New England, Canada, and Alaska and then reversing course this time of year, peeping their way during nighttime migrations past the Three Rivers south into Mexico, Panama, Bolivia and beyond.

When they first arrive on breeding grounds, males claim and defend territories, sometimes dueling in song with rivals, then pairing up with females, the nest builders of the team. Females build open nests that include bark, moss, and twiggy materials 3 to 10 feet off the ground in shrubs or trees. Three to four pale blue eggs are soon incubated, and the young hatch after about two weeks. Another two weeks of frantic infant care and prodigious growth and the new Swainson’s Thrushes are fledged and big enough to manage on their own. They eventually join their parents as they head south, the first test for any hatching-year bird. Many will perish along the way, but enough will make it south of the equator and back again next spring to sustain the species. In fact, Swainson’s Thrushes are considered stable by conservation measures, a species of “least concern.”

This time of year, listen on cooler, clear evenings for the telltale call notes of migratory Swainson’s Thrushes. Given in flight, these resemble the calls of spring peepers in the night and remind us of the invisible movements of birds overhead.

To hear Swainson’s Thrushes, visit http://pjdeye.blogspot.com/2009/02/thrush-calls.html.