Stefan Lorant, The Conclusion

Although disaster had been briefly averted, the key word was “briefly,” as we’ll see in the final episode of this series, which I’ll call:

More Trouble in Lenox

Previously in this series: Stefan Lorant Part VI, Of Charm and Disaster

Lorant and I were passing through the kitchen on our way out the back door for our tour of the property. I realized that my briefcase was still slung over my shoulder and so I set it down on the kitchen table, and off we went.

Stefan had a lovely garden off the terrace behind the house and, down a long, sloping hill there was a pleasant meadow with the Berkshire Mountains as a backdrop. On the way down to the meadow I noticed an attractive outbuilding on the property, a few hundred yards from the main house. It turned out to be both a writer’s retreat and a guesthouse.

The place was small but quite charming, just a living room, bedroom and bathroom, but pleasant and cozy. As we entered the bedroom Stefan pointed to the bed and said, “Lie down on that bed!”

It was a weird thing to say and I simply responded, “I’m not tired, Stefan.”

“Lie down on that bed!” he commanded.

Startled, I lay on the bed, on top of the covers, and stared up at him.

“Okay,” he said, “you can get up now.”

I climbed out of the bed and Stefan put his arm around my shoulders and his mouth against my ear and said, “Now you can say, ‘I slept in the same bed with Marlene Dietrich!’” He roared with laughter. I found out later that Stefan often pulled this stunt on his male guests.

The time was rapidly approaching when Betty, Susan and I would have to leave for the airport, so, as we headed back toward the house I delicately broached the subject of the photo collections. But as soon as I mentioned Susan’s name Stefan roared, “She’s nothing but a professor!”

I’ve mentioned that Stefan hated publishers and foundation presidents. Apparently, he also hated professors.

“What’s wrong with that?” I asked.

Stefan went into a long rant about how professors were mere pedants who spent their lives trying to destroy every dollop of creativity in their students. He wanted nothing to do with them.

I said, “You’ve got Susan all wrong, Stefan. Sure, she’s a professor, but that’s only because she has to make a living. She’s actually a professional photographer, and a very talented one.”

Stefan frowned at me. He admired nothing so much as creative talent and I could see he was annoyed at the possibility that he might have to change his opinion of Susan. So I pursued my advantage. “When we get back to the house,” I said, “ask her about her photography. Then you can decide what you think.”

Stefan merely grunted, but it seemed to me that I’d made some progress. Maybe we would get to examine the photos after all.

We entered the kitchen and headed toward the front of the house, where Betty and Susan were waiting for us. But then I remembered I’d left my briefcase in the kitchen, and I went back for it, saying to Stefan, “I’ll be right with you.”

I found my briefcase right where I’d left it, paused to get a drink of water from the kitchen faucet, then headed to the front room. I don’t know what had happened in my absence – and I don’t completely know to this day – but as I approached the front of the house Susan was storming out the front door and Betty was wringing her hands and looking helpless. Lorant, meanwhile, had his back to these proceedings and was calmly sorting the day’s mail and humming a jaunty tune.

* * *

Over the next year I spent an inordinate amount of time trying to head off the Pittsburgh community’s desire to sue the hell out of Lorant for “stealing” the photos. I was hopeful that Lorant would, in the end, do the right thing, but the rest of the community had given up on Stefan. In particular, they were worried that Stefan might die and leave the photos to someone else, or that he might be selling the photos privately. They wanted a court to confirm our title to the Pittsburgh book photos.

I successfully headed off the lawsuit, but in the end I was wrong and they were right – Stefan died and his estate was a mess. Lorant had been married four times, but that was merely the tip of the iceberg. After his death Lorant’s biographer, Michael Hallett, found five file drawers full of love letters from, by Hallett’s count, no fewer than 116 women. It sometimes seemed to me that all 116 of them had filed claims against his estate.

Amazingly, even though Lorant had died, Bruce and Gail Campbell got the fifth edition of the Pittsburgh book – the so-called “Millennial Edition” – completed and published. It was a big accomplishment and a kind of epitaph for Lorant.

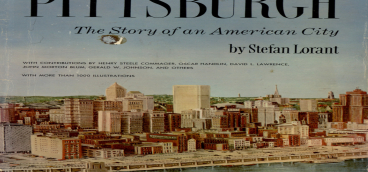

In the end the problems with Stefan, maddening though they were, paled next to his astonishing accomplishments. He was perhaps the greatest photojournalist who ever lived and he had achieved remarkable things in at least three different countries. Pittsburgh: The Story of an American City, began as a kind of vanity project and a way for Stefan to make some money. But after the glitter of Lorant’s genius had been applied to it, it is no exaggeration to say that it is probably the best book ever produced about one city.

As Michael Hallet put it, Lorant’s “urban biographical opus … narrated the story of the personalities and visionaries” that created and reinvented the city of Pittsburgh. “He produced the elegant concept for a pictorial biography of a city, a concept and a masterpiece that has yet to be surpassed.”

Even today, a quarter century after Lorant’s death, it’s a rare week that goes by when I don’t hear in my memory his booming, heavily accented voice: “Gregory! How are you, my friend?”

Next up: Panic Is a Virus