Standing the Test of Time

Never before has the nation been presented with the distinct possibility that a woman or a man of color could be elected president. Yet here it is: the two front runners for the Democratic nomination are New York Sen. Hillary Clinton and Illinois Sen. Barack Obama.

their children in case of legal separation. Divorce was rarely granted and then only for the most flagrant abuses: adultery, desertion, non-support or extreme cruelty.

Many women, especially those of status, bristled at the restraints. Abigail Adams wrote to her beloved husband, John, when he was in Philadelphia in March 1776 attending the First Continental Congress: “I long to hear that you have declared an independency. And, by the way, in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power in the hands of husbands.

“Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation. That your sex are naturally tyrannical is a truth so thoroughly established as to admit of no dispute; but such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of master for the more tender and endearing one of friend. Why, then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity? Men of sense in all ages abhor those customs that treat us only as vassals of your sex. Regard us then as being placed by Providence under your protection and in imitation of the Supreme Being make use of that power only for our happiness.”

As campaigns seek to woo voters by the millions, it’s easy enough to forget that Clinton’s and Obama’s predecessors fought for centuries to get any rights equal to those of Caucasian men — especially the right to vote.

The founders of our state and nation maintained an overarching conviction that the elective franchise — the right to vote — should be granted on a selective basis. Color, gender, property ownership, wealth, class, literacy, residency, citizenship status, mental health, conviction for commission of a felony and religious belief disenfranchised some and enfranchised others. Pennsylvanians played a major role in changing that.

The Founding Fathers limited the vote to free, white male residents, who were 21 or older, owned property and paid taxes. Pennsylvania’s population at that time consisted in part of free men and women (including people of color) who were more often than not farmers, shopkeepers, craftsmen and artisans. Most were not wealthy; they worked hard to maintain themselves and their families. Some had come seeking relief from oppression in their native lands. Others were drifters or adventurers, and some were ne’er-do-wells or escaped felons. The so-called Native Americans were considered dangerous savages and heathens, a bothersome presence regarded as enemies and inferiors.

Another group was labeled “servants.” Part of this class were people of color, sold or kidnapped from their home lands, transported to the New World and forced into slavery. Although free men and women of color lived in this land from earliest times, they were considered to be and were treated, for the most part, like slaves. The other part of the servant class were indentured European men and women bound to service for a time to pay for their passage across the ocean. A Pennsylvania colonial law enacted in 1700, titled “An Act for the Better Regulation of Servants,” restricted daily activities of all servants. One illustrative provision dealing with embezzlement said that any white person dealing with servants for goods or services without the okay of the master would forfeit triple the amount of the value of the goods. White servants would see their servitude extended, and black servants would be severely whipped in “the most public place.”

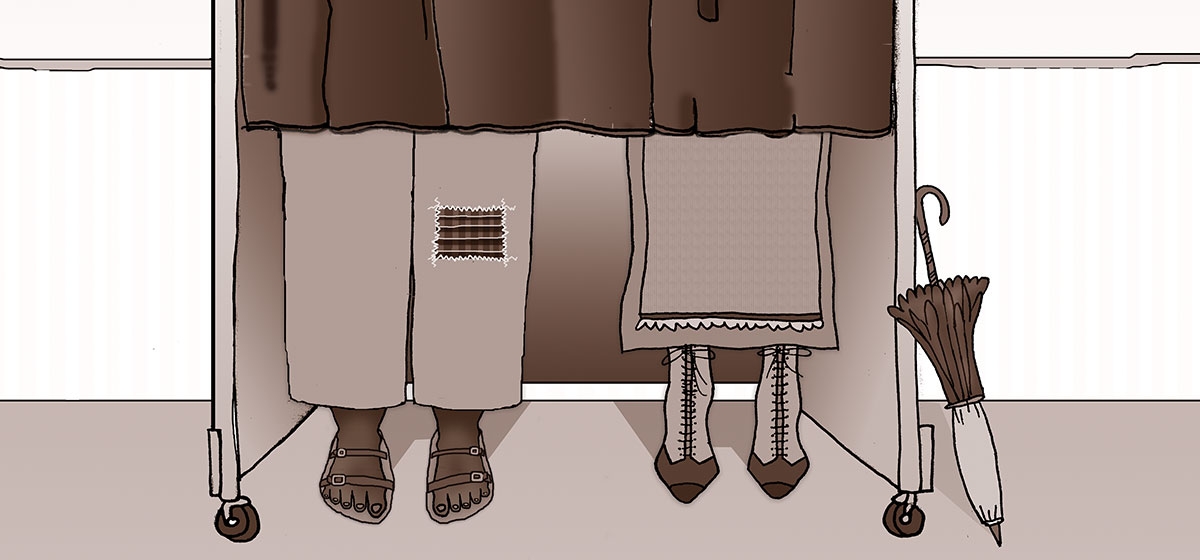

White women who were not indentured servants also faced formidable controls. No matter their social standing, under English common law, women had many responsibilities but few, if any, rights. Married women, especially, experienced what was a “civil death.” Upon marriage, they had no right to property and no legal existence apart from their husbands. The concept may seem strange and unimaginable today, but a woman, from the moment of marriage, was legally deemed to be covered — a femme coverte — under the wing, cover or protection of her husband. That concept held well into the 19th century. Married women could not sign contracts; they had no title to their own earnings or to property, even if it was theirs by inheritance or dower. They had no authority with

Her husband responded two weeks later: “As to your extraordinary code of laws, I cannot but laugh. We have been told that our struggle has loosened the bonds of government everywhere; that children and apprentices were disobedient; that schools and colleges were grown turbulent; that Indians slighted their guardians, and Negroes grew insolent to their masters. But your letter was the first intimation that another tribe, more numerous and powerful than all the rest, were grown discontent… Depend upon it, we know better than to repeal our masculine systems. Although they are in full force, you know they are little more than theory. We dare not exert our power in its full latitude. We are obliged to go fair and softly, and, in practice, you know we are the subjects. We have only the name of masters, and [giving this up] would completely subject us to the despotism of the petticoat.”

David McCullough suggests in his biography of John Adams, from which these quotes were taken, that this exchange is a humorous one: “She [Abigail] was not entirely serious. In part, in her moment of springtime gaiety, she was teasing him. But only in part.” A close reading suggests that this matrimonial repartee contained a bit more bite than banter. Abigail also expressed her opinions in a letter to her husband about slavery in the context of the concept that all men were created equal: “I wish most sincerely that there was not a slave in the province. It always seemed a most iniquitous scheme to me — [to] fight ourselves for what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have.”

Women were not the only ones speaking out and writing about the incompatibility of the founders’ quest for liberty and equality for themselves while they denied those same “rights” to women and people of color. Thomas Paine was among the first to publicly condemn the status of women. In “An Occasional Letter on the Female Sex” published in the August 1775 edition of the P ennsylvania M agazine, Paine described the awful status of women in the world, generally, and then noted: “Even in countries where they may be esteemed the most happy, [they are] constrained in their desires in the disposal of their goods, robbed of freedom and will by the laws, the slaves of opinion, which rules them with absolute sway and construes the slightest appearances into guilt, surrounded on all sides by judges, who are at once tyrants and their seducers.”

Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia was a physician, scientist, early opponent of slavery and signer of the Declaration of Independence. He proposed expanding the education of females to prepare them for the equal share that every citizen has in liberty, including an equal share in the government.

T he L ady’s M agazine and R epository of Entertaining K nowledge is said to be the first American periodical devoted exclusively to women. Published in Philadelphia during 1792 and 1793, it featured a long and very favorable review of Mary Wollstonecraft’s famous “Vindication of the Rights of Women.” Wollstonecraft, an English woman known as the “mother of feminism,” proposed that intellect should always govern and that women should acquire strength of mind and body. She believed that “soft phrases, susceptibility of heart, delicacy of sentiment, and refinement of taste, are almost synonimous [sic] with epithets of weakness.”

It would take more than a century for women’s equality to become a dream and then a reality. The nucleus was the anti-slavery movement, and Philadelphia played a key early role. In 1688, the Mennonite Quakers — a.k.a. the Germantown Friends — declared slavery to be contrary to Christianity. In 1775, the primarily English Pennsylvania Quakers formed the first antislavery society. Under the leadership of Quaker activists such as Anthony Benezet and John Woolman, many Philadelphia slave owners of all denominations began emancipating their slaves. Benezet was instrumental in convincing Benjamin Franklin and Rush to join the effort when the Pennsylvania Abolition Society was organized in 1784.

Prior to 1780, free people of color in Pennsylvania were subject to the same laws and regulations that applied to slaves. Pittsburgh at that time was still the frontier, with little formal governmental structure. Laws were not strictly followed. Besides, on the frontier, few men owned slaves, and most of the population cared more about a person’s skills than his or her status. Nevertheless, a colonial statute of 1726 stated that Negroes were “an idle and slothful people,” and magistrates were directed to bind out (impose a legal obligation to serve another person) free Negroes for “laziness or vagrancy.” Further, free Negroes were forbidden to harbor Indian or mulatto slaves on pain of punishment by a fine of five shillings.

Whether slave or free, people of color were tried in separate courts; they did not have the right to trial by jury and, if found guilty, they were subjected to harsher penalties than whites. The law also forbade marriage between a person of color and a white person. The free person of color who violated this law was to be sold into slavery, while the white person was indentured to seven years of servitude. The law also prohibited sexual relations between people of color and whites. Free people of color, along with slaves, were not allowed to frequent “tippling houses,” carry arms or gather in companies larger than four Negroes on any day including the “First Day,” except on the “master’s business.” The penalty was public whipping at the discretion of the justice of the peace, not exceeding 39 lashes.

The status of free men of color was always problematic. They had hoped to find clarity with the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution following the Civil War. For most of the 19th century, however, the Supreme Court narrowly construed those constitutional provisions to the disadvantage of the men and women they were intended to aid. The white woman would have to wait until 1920 for political equality. Both would have to struggle for decades before the law removed legal, political and social barriers. Pennsylvania’s legal history in the suffrage struggle is at once interesting, troubling, disheartening and confusing. In 1836, the constitution of the Commonwealth delineated the criteria. It read in part: “In elections by the citizens, every freeman of the age of 21, having resided in the State two years next before the election, and within that time paid a State or county tax, which shall have been assessed at least six months before the election, shall enjoy the rights of an elector.”

Under this provision, a free Negro named William Fogg of Luzerne County sought to register to vote. Fogg, however, was denied registration and the right to vote even though he proved that he met the requirements. He sued. After reviewing the facts, the judge directed the jury to decide in Fogg’s favor. The defendants appealed, claiming the trial court incorrectly ruled that there was no provision in Pennsylvania law that prohibited free Negroes or mulattoes from voting.

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania reversed the verdict and judgment. Chief Justice John Bannister Gibson wrote for the unanimous court, saying the question was whether the word “freeman” included a man of color. The court decided that it did not, with the underlying rationale being the assumption that all black men were inferior. The Chief Justice reasoned that, if the declaration of universal and inalienable freedom in the Declaration of Independence was meant to include the “colored race,” it would have abolished slavery, but slavery persisted long after 1776. Second, the colored race took no part in the “social compact” that was entered into by the founders of the Commonwealth and the nation. Third, “[O]ur ancestors settled the province as a community of white men, and the blacks were introduced into it as a race of slaves.” Finally, Negroes had no citizenship in other states and suffered disabilities under state laws and constitutions as well as the federal constitution. How could Pennsylvania confer freedom and citizenship so as to overbear the laws imposing countless disabilities on them in other states?

This ruling was rendered 20 years before the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1857 decision in the Dred Scott Case. Chief Justice Taney, speaking for the court majority, concluded that the Negro was not to be included in the general definition of citizen of the U.S. and it was up to each state to determine whether or not state citizenship was to be extended to people of color. Justice Taney also proclaimed that the Negro was considered to be so inferior that he had no rights which a white man was bound to respect.

The Pennsylvania high court’s decision in the Fogg case was followed by a proposed convention to amend the Pennsylvania constitution to exclude Negroes from voting. This evoked an immediate response from the Negro populations in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. In June 1837, leading African-Americans of Pittsburgh, including John Vashon, Lewis Woodson, Samueal Ranvolds, Joseph Mahonney and Samuel Ranyolds, prepared a report to the convention. Titled “The Memorial of the Free Citizens of Color in Pittsburg, 1837,” it appealed to the delegates’ logic and moral conscience. It declared that, since people of color of Pittsburgh were progressive and of good character, paid property and poll taxes and owned real estate, they met the requirements of freemen and electors and were entitled to vote.

Disenfranchisement, To The People of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1838. It was prepared by leading black abolitionists such as Robert Purvis, James Forten and William Whipper. The appeals were to no avail. On Jan. 20, 1838, the constitutional convention held final debates to limit suffrage to “white freemen.” After almost 10 hours of debate, the amendment was approved 75-45.

The general public also opposed women’s suffrage, and agitating for women’s suffrage was considered to be undignified and unacceptable. As late as 1848, the Philadelphia Ledger extolled the virtues of the woman who understood and joyfully accepted her role in life: “Whoever heard of a Philadelphia lady setting up for a reformer, or standing out for women’s rights, or assisting to man the election grounds, raise a regiment, command a legion, or address a jury? Our ladies glow with a higher ambition. They soar to rule the hearts of their worshipers, and secure obedience by the scepter of affection…. But all women are not as reasonable as ours of Philadelphia. The Boston ladies contend for the rights of women. The New York girls aspire to mount the rostrum, to do all the voting, and we suppose, all the fighting, too…. Our Philadelphia girls object to fighting and holding office. They prefer the baby-jumper to the study of Coke and Littleton; the ball-room to Palo Alto battle…. A woman is a nobody. A wife is everything. A pretty girl is equal to ten thousand men, and a mother is, next to God, all powerful….. The ladies of Philadelphia, therefore, under the influence of the most serious sober second thoughts, are resolved to maintain their rights as Wives, Belles, Virgins, and Mothers and not as Women.”

Leaders of the African-American community in Philadelphia also prepared memorials to the convention. One was called The Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, Threatened With Lucretia Coffin Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton — two of the most famous suffragists — and others formally initiated the struggle by writing and signing a “Declaration of Sentiments” (modeled after the Declaration of Independence), which called for the full extension of basic rights, including the right to vote and to hold property, to all women. By far the most prominent of the 32 men at the conference was Frederick Douglass, the former fugitive slave, who became a leading figure in both the abolitionist and women’s rights movements.

In 1833, Mott had founded the first Female Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia, because as a woman she was barred from membership in Abolitionist organizations. Also in Philadelphia, James Forten, his wife and three daughters helped established the Anti-Slavery Society. It was the first time that most of the women were exposed to managing an organization, and they developed skills in arranging meetings, preparing agendas, conducting petition campaigns and raising funds. As Elizabeth Cady Stanton put it, the female anti-slavery conventions were “the initial steps to organize public action and the Woman Suffrage Movement per se.”

One of the early victories in the women’s equal rights struggle in Pennsylvania was the enactment of legislation removing some legal constraints on property ownership. Under the new law, all property held by a single woman could continue to be hers after marriage. It also provided that a woman might acquire additional property during the marriage, that her property could not be sold to pay her husband’s debts and that she could dispose of her property as she saw fit. The governor signed the law just before the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848.

Initially, the Pennsylvania suffrage movement aimed at educating the public at large. They held meetings, wrote articles for newspapers and magazines and distributed literature. Annual conventions were held in Lancaster, Pittsburgh, Easton, West Chester, Lewistown, Norristown and Harrisburg. Philadelphia was the center, and the issue gained support. Several Pennsylvania publications supported the cause. T he Philadelphia Woman’s Advocate, edited by Anna E. McDowell, advocated women’s rights to work and equal pay for equal work. In her Pittsburgh Saturday Visiter [sic], Jane Grey Swisshelm supported women’s rights, temperance and abolition.

Following the end of the Civil War, the tempo for women’s rights quickened, but there were major setbacks. In 1866, the American Equal Rights Association organized to advance the interests of people of color and women. The Association’s primary objective was removing legal restrictions on the right of Negroes and women to vote. Lucretia Mott was chosen as its first president and Elizabeth Cady Stanton was first vice president. The organization, however, was doomed from the start.

A schism developed among the membership. Abolitionists and so-called Radical Republicans believed Negro suffrage should trump women’s suffrage. In their view, both could not be attained at the same time, so women’s suffrage would have to wait. Equally devastating were actions of the Congress. One added a provision in the Fourteenth Amendment advancing the cause of Negro suffrage. The other was the enactment of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1869, which said that the right of citizens to vote “… shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The decision not to include sex or gender was deliberate.

In 1869, the first formal meeting of suffragists in Pennsylvania was held in Philadelphia, and the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association was organized. In the 1870s suffragists became more militant. Some sought to bring legal actions against the denial of the right to vote. Some appeared at polling places and tried to cast ballots. Susan B. Anthony was tried and convicted in Rochester, N.Y., of “knowingly, wrongfully and unlawfully” voting in the presidential election of 1872. However, she was not incarcerated nor did she pay a fine.

In Pennsylvania, Carrie S. Burnham sued for her right to vote, basing her argument on the language of the Pennsylvania Constitution. Thirty-five years after William Fogg of Luzerne County was denied the right to register to vote and the constitution was amended to exclude black males, Burnham, a bright 21-year-old Philadelphian, had just paid her taxes, and her name was registered on the printed list of legal voters. So on Election Day, Oct. 10, 1871, she presented her ballot at the proper time and place. Election officials refused to receive her vote.

Burnham and her lawyer immediately went to court citing the Pennsylvania Constitution and statutes as well as the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Pennsylvania Constitution contained the amended provision limiting the vote to “white freemen.” The Fourteenth Amendment, adopted after the Civil War, stated, in essence, that all persons born or naturalized in the U.S. are citizens of both the U.S. and the state where they reside and that no state shall abridge the “privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; no state shall deprive any person of life, liberty or property, without due process of law, nor shall any state deny to any person in its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” She also cited the Fifteenth Amendment, which specifically prohibited any state from denying the right to vote on account of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The defendants filed a demurrer, which is essentially a legal “So what!” Arguments were heard, and the court rejected her suit. Essentially, the court ruled the privilege of voting had never been intended for women in any of the documents Burnham cited. The court pronounced the final obituary: “We can say that we have in Pennsylvania a uniform and uninterrupted usage of nearly two hundred years, showing that women were never intended to possess the elective franchise.” In April 1872, the Supreme Court of the Commonwealth upheld the ruling without opinion. Similar to the Fogg case, the courts rejected women’s rights to vote and a constitutional convention confirmed the denial.

The convention in 1872 and 1873 considered expressly limiting the privilege of voting to male citizens over 21 who met the other requirements. Petitions supporting women’s suffrage came in, and the debate lasted a week. Opponents said a woman’s place was in the home, that women were adequately represented at the polls by their male relatives, that women’s suffrage would promote family discord and that women would be degraded by participating in political matters. They said that women, generally, did not want the right to vote and would not take advantage of it if it were granted. Women’s suffrage advocates sought a referendum on the matter, asserting that voting was a natural right, that many women had no men to represent them, that women’s suffrage would elevate politics and make it more civil and that it might bring about the possibility of control of the evil of liquor. In the end, there was no referendum.

After the U.S. Supreme Court again ruled against women in 1874 in Minor v. Happersett, the future looked bleak. But the struggle didn’t end. On July 4, 1876, in celebration of the centennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Susan B. Anthony read to an assembly of an estimated 150,000 people her now-famous “Declaration and Protest of the Women of the United States” at the statue of George Washington in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Initially, the National Women’s Suffrage Association had requested permission merely to present their Declaration at the conclusion of the reading of Jefferson’s Declaration by Richard Henry Lee, of Virginia. The request was denied. However, since Anthony and several colleagues had been invited, they decided to take the stage and read — not merely present — the document to the large assembly, which included the Vice President of the U.S. and foreign dignitaries. The Declaration included a demand for women’s right to vote. This bold act catalyzed the movement.

Recognizing that the courts wouldn’t help them, suffragists turned to state and federal legislatures. In 1878, a constitutional amendment was proposed that provided that “The right of citizens to vote shall not be abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” This proposed amendment would be introduced in every session of Congress for the next 41 years.

The first attempt to get a similar resolution introduced into the Pennsylvania State Legislature was made in 1911, to no avail. In January 1913, the resolution was again introduced and was passed by the House of Representatives by a wide margin.

After a long, close and bitter fight in the Senate, the resolution was passed. The resolution was again passed by the legislature in 1915, for the required second time, but it was defeated in the general election where only men were allowed to vote.

But the drive to obtain the right to vote was building a full head of steam, both nationally and in the state. On the national front Alice Paul led the campaign for the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment. Born in 1885, she had degrees from Swarthmore, Penn and the London School of Economics with a master’s in sociology and a Ph.D. in political science. Her dissertation topic was “The Legal Position of Women in Pennsylvania.” She was a determined activist.

When Paul was in England in 1908, she was inspired by Christabel Pankhurst, a leading English suffragist. There she joined the Women’s Social and Political Union, where her activities led to her arrest and imprisonment three times. She went on a hunger strike and had to be force-fed. When she returned to the U.S. in 1912, she joined the National Women’s Suffrage Association and was assigned to raise funds and awareness. She focused on lobbying for a constitutional amendment. When efforts proved unproductive, Paul and her colleagues formed the National Women’s Party in 1916 and began to employ the aggressive tactics she had learned in England: demonstrations, parades, mass meetings, picketing and hunger strikes. In the 1916 national election Paul and the National Women’s Party campaigned against President Woodrow Wilson and the Democratic Party for their refusal to support the Suffrage Amendment.

Her organization staged the first political protest ever to picket the White House. The pickets, called the “Silent Sentinels,” held a large banner demanding the right to vote. The nonviolent, civil disobedience effort ultimately led to the pickets’ arrest on charges of “obstructing traffic.” She and others were convicted and imprisoned. Paul commenced a hunger strike in protest over prison conditions, and she was moved to the prison’s continued demonstrations kept pressure on the Wilson administration. Paul then organized 8,000 women to parade through Washington, and in January 1918, President Wilson announced that women’s suffrage was urgently required as a “war measure.” In 1919, the House voted to support the enfranchisement of women, and the Senate followed suit. The women’s suffrage movement moved quickly to obtain the necessary votes from the states for ratification.

In Pennsylvania, similar efforts were under way. One of the most interesting and effective was the so-called “Pittsburgh Plan,” which involved a series of innovative attention-getting actions aimed at educating women and lobbying for women’s suffrage. Jeannie Bradley Roessing, Mrs. Julian Kennedy and Mary Bakewell were primarily responsible. One of their most noteworthy activities was a parade on May 2, 1914. Mrs. Kennedy led the massive rally, followed by Roessing and Bakewell. It was part of a nation-wide observance of Woman Suffrage Day and commenced at the Monongahela Wharf, led by six motorcycle policemen. The rally wound its way through Downtown to Schenley Park and then into town again, reaching the Jenkins Arcade Building. Seven stands were erected on the “Frick Lot,” from which 30 speakers addressed the crowd.

The Pittsburgh Press reported on the march, which included representatives from states that had enacted suffrage legislation, delegations from various colleges, including the Pennsylvania College for Women, now Chatham University, and many representatives of suffrage groups, including a delegation of Negro women suffragists. One of the parade’s highlights was the appearance of the “Liberty Bell,” which was an exact replica of the original in Philadelphia. It sat on the bed of the truck that Jennie Bradley Roessing drove to all 67 counties in the commonwealth to spread the word and raise money. (A replica of this parade can be found at the Carnegie Science Center’s Miniature Railroad & Village.)

On June 4, 1919, the required twothirds vote in favor of the women’s suffrage amendment was finally obtained in Congress. Pennsylvania’s legislature quickly ratified it on June 27, 1919, becoming the eighth state to do so. The requisite threefourths majority (36 states) was reached on Aug. 18, 1920, and the president signed it. The Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution was succinct: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

At long last, in the eyes of the law, most men and women of all races and creeds were able to vote.