I only met my husband’s grandfather a few times; he died at age 92, shortly after my husband and I were married in 1988.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”110″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

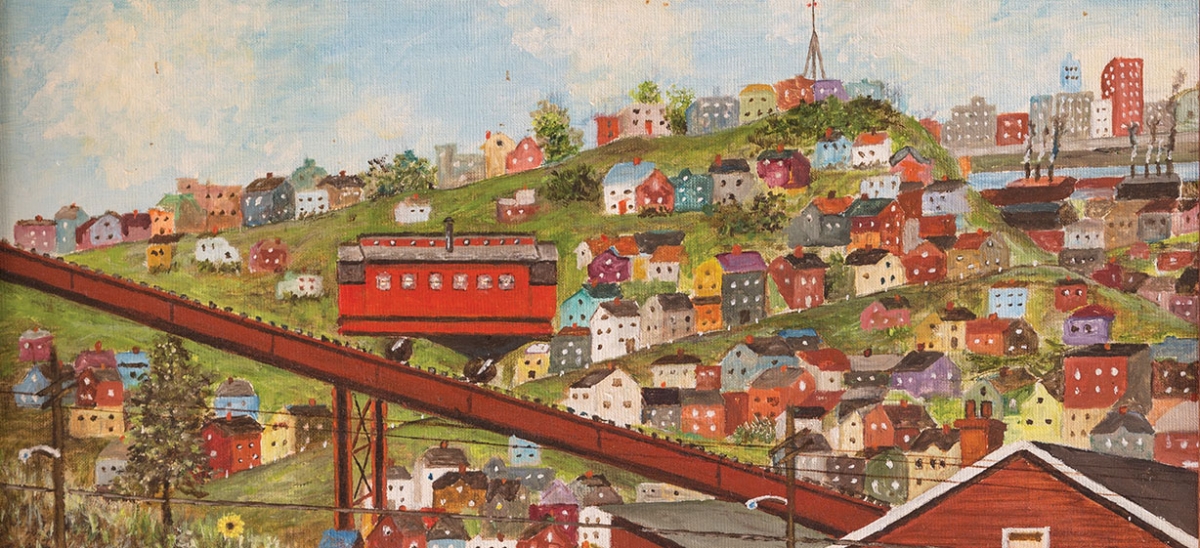

However, I think of Lee Dittley often, when I look at his charming paintings of the South Side of Pittsburgh. With only a ninth-grade education, he went from working in a glass factory, to a cooperage at the Oliver Iron and Steel Factory, to painting signs. He went on to become a commercial painter, a civil servant with the Bureau of Mines and, finally, an artist who created striking scenes of his lifelong home and beloved South Side.

I know his story because along with his paintings and his daughter’s (my mother-in-law) memories came a booklet published in 1978 by The Birmingham Union, “From These Slopes and Flats: Lee Dittley’s Old South Side.” The booklet was supported by a grant from an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Dittley was interviewed and his works photographed for this project in recognition of the historical, ethnic and cultural significance of the life he captured in his paintings of his community.

Dittley was born in September 1896 in a small house on South 15th Street, in the shadow of St. Michael Church. His father was a Swiss immigrant and his mother was a coal miner’s daughter. He would live in that house until his death in 1989, and when he was interviewed for the booklet at 82, he remembered many details of his childhood.

It wasn’t easy for immigrants as they struggled to make a living in the early 1900s in Pittsburgh. Children were sent to work in the mills and foundries. Dittley remembered carrying hot glassware on an iron paddle from the molds to the oven used to temper the glass when he worked at King’s Glasshouse on 18th Street.

The brutally hot factory had iron bars on the windows to prevent the children from going outside to cool off. Later, when he worked at the Oliver Iron and Steel Foundry, the machinery was so loud that workers were deafened for hours after their shift. At both jobs, Dittley worked from 6:45 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday through Friday and 6:45 a.m. to 4 p.m. on Saturdays. He earned $4 a week.

Growing up on the South Side, however, wasn’t all toil and struggle. Dittley remembered winter sledding and skating down Pius Street, summer baseball games, and carnivals at St. Michael Church. He recalled the merrygo- round, swings, a shooting gallery, a dummy stand, a bowling alley, a cane pitch game and lemonade and ice cream stands.

There was the neighborhood policeman, Frank Nugent, who would rap his nightstick on a railing, sending all of the children home in the evening. The lamplighter carried an 8-foot ladder from light post to light post, igniting them each evening and then retracing his route, from Allentown, down Brosville Street to South 15th Street, in the morning to extinguish them. Dittley accompanied his mother to the South Side Market House, buying eggs and meat that were brought in from farms in the suburbs. The farmers set up stalls outside selling butter and cheese, fresh fruit and vegetables and poultry. Inside there were counters with racks of cattle and pigs. Dittley called his childhood “grand and glorious.”

His fondest memories were of the four inclines—the Knoxville, the Mount Oliver, the Castle Shannon, and the St. Clair—that climbed the slopes of the South Side during his youth, all of which are now gone. He would sit for hours, watching them as they made their way up and down the steep terrain from the commercial area to the hilltop communities. I suspect the Knoxville Incline, which figures prominently in one of his paintings, was his favorite incline because it had a curve in it and carried not only passengers but livestock, wagons and later, automobiles.

As a young man, Dittley painted pastoral landscapes for his friends and family as a pastime. He gave up painting when the demands of earning a living and raising six children became all-consuming.

Lee Dittley remebered winter sledding and skating down Pius Street, summer baseball games, and carnivals at St. Michael Church.

When he retired from the Bureau of Mines in 1961, his daughters bought him a paint set, and he started again, cramming his 6-foot, 3-inch frame into a tiny “studio” under his basement steps and painting oil on canvas. He was very thrifty and short on patience and so he thinned his paints to make them last longer and dry more quickly.

This time around, instead of painting landscapes, he turned to his neighborhood, painting primarily buildings and street scenes. He never took an art class and was completely untrained, which according to the Birmingham Union booklet, probably helped him because he never struggled with perspective, scale or spatial relations.

“I simply move things around until they fit,” he said. His primitive, two-dimensional paintings have naïve foreshortenings, probably a result of his sign-painting days when signs had bold, simple, flat letters and objects. He found painting people very difficult, so he just eliminated them from his scenes, though the South Side was bustling with people and activity, as it is today. Anything else he found difficult to paint he just covered up with either snow or trees.

The South Side was the only place Dittley ever knew. He called the community an artist’s paradise.

He also didn’t paint the gritty South Side of the early- and mid-20th century. He ignored peeling paint, soot, grime and eliminated garbage from his paintings, portraying a cleaned-up, not entirely realistic version of what he saw. He believed there was too much ugliness already, and he didn’t want to depict more in his paintings. He often painted from photographs, making adjustments so that they were not just copies. He painted buildings and houses as he remembered them from his childhood rather than as they were at the time.

And he let his imagination guide his hand. In some scenes the houses are farther apart than they actually were, lawns were added, and scenes combined. One painting, “South Side Winter,” completed in 1977, is instantly recognizable as the South Side, with boxy houses scattered on a hillside and long, narrow staircases connecting the streets, with the Downtown Pittsburgh skyline in the background. But it’s a place that can’t actually be found.

The South Side was the only place Dittley ever knew. He was fiercely proud of it and was able to capture its charm and uniqueness. He called the community an artist’s paradise. There were picturesque views everywhere. It was (and still is) a wonderful mix of residential, commercial, and industrial areas, so there was plenty to paint: houses, churches, shops, taverns, roofs, smokestacks, inclines, steps, streetcars, horses, cars and cobblestones. “Why go up to Mt. Washington?” he said. “Those scenes are a dime a dozen. All that an artist could ever want is right here!”

We don’t know how prolific Dittley was or where some of his paintings are, but we are grateful for the ones that we have, the documentation of his memories and a glimpse, albeit painted over, of the South Side of old. The Birmingham Union booklet says, “The artist’s only stated goal is to create a painting which will cause old-timers to say, ‘surely that was the way it was.’”

And it was, wasn’t it?