Snow Birds Fly Away—to Pittsburgh

When we hear of snow birds this time of year, the first thing that comes to mind is probably grandparents in Florida. “At least,” we think to ourselves, “they have the good sense to fly somewhere warm.”

The same might be said of a bird that I never see except in western Pennsylvania’s coldest months: the snow bunting. An avian denizen of the high arctic and bare tundra, birds of this species can fly farther to reach us in the Pittsburgh region than we travel to meet family in sunny places like Miami or Boca. Relative to their distant breeding grounds, Pittsburgh is Key West to them, or even farther south. (Seeing the more familiar dark-eyed junco, a regular winter feeder bird that breeds in the north, is more like a quick visit from a cousin down from Erie.)

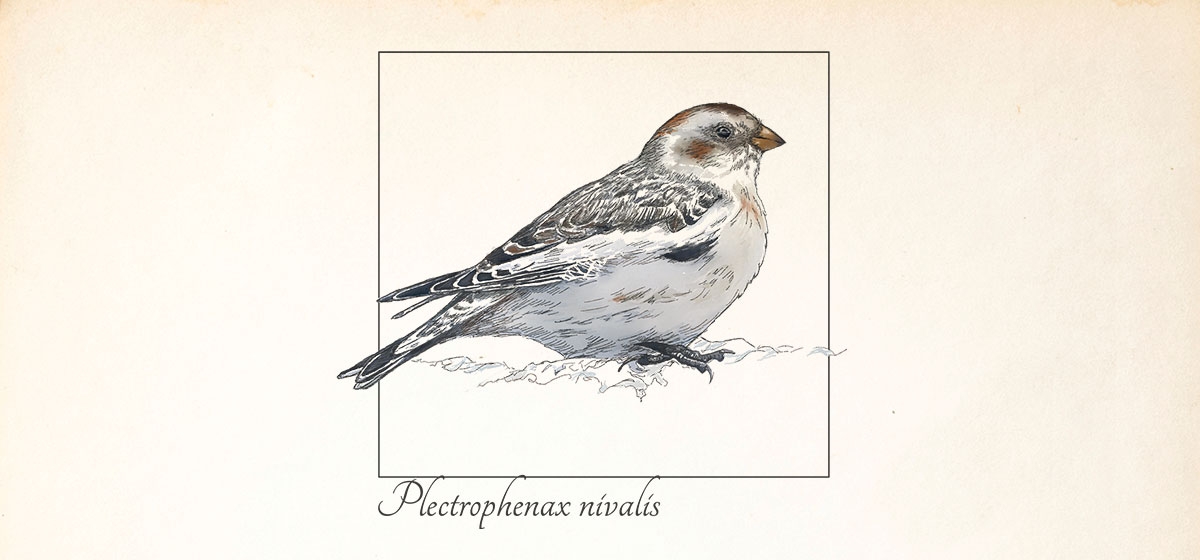

In winter non-breeding plumage, snow buntings look not unlike big sparrows, but white wing patches, chests and underwings that seem like cascades of swirling snowflakes when they fly immediately give them away as something altogether different. A group of these hearty travelers is called a “drift,” and for good reason as they lift and spin from a stubbly edge of road or field. Snow buntings can almost disappear right in front of you, as I’ve observed numerous times, they blend into the winter color scheme so well.

So where can you see these arctic visitors? You’ll have to drive a bit, up I-79 or 376 north toward Volant in Lawrence County or the New Wilmington area or farther afield to Pymatuning State Park and its causeway. An excellent source of recent and historical sightings is ebird.org, a free, online, real-time database of bird sightings from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology that allows users to look up a species or a place. Starting in November, check the website to see if reports of snow buntings are current and beat a trail north. It’ll be worth the trek.

For all the delight this unusual guest will bring you in winter, in summer, when they’re found thousands of miles to the north on open, rocky nesting grounds, changes in their plumage will please you all the more. Similar to neotropical warblers that birders so look forward to seeing each spring, snow buntings swap drab winter colors for clean breeding finery—by wear and abrasion of feathers rather than molting. Pure white and black feathers on the males, which are like white dinner jackets on these handsome fellows, have been hiding there all along, made visible in spring as the browns and tans fall away leaving only the white and black behind.

I’ve only seen the seasonal summer bird in pictures, though I understand that in some arctic communities, these guys will actually take up residence in bird houses, the northern latitude’s version of luxury living, it seems. If you find yourself in the land of the midnight sun, you’re more likely to see a seed and insect eater tending to a bulky nest of grasses and moss hidden in a rocky crevice. Females lay a half dozen or more pale eggs and get to the business of continuous incubation, vital in the chilly but bright summers, as males forage for meals. Incubation lasts about two weeks and fledging happens after hatching in the same time span, so within a month the business of the species is largely done. Then it’s feast, fatten, and prepare for the cold to come, perhaps with a jaunt south come winter to warm, sunny western Pennsylvania.