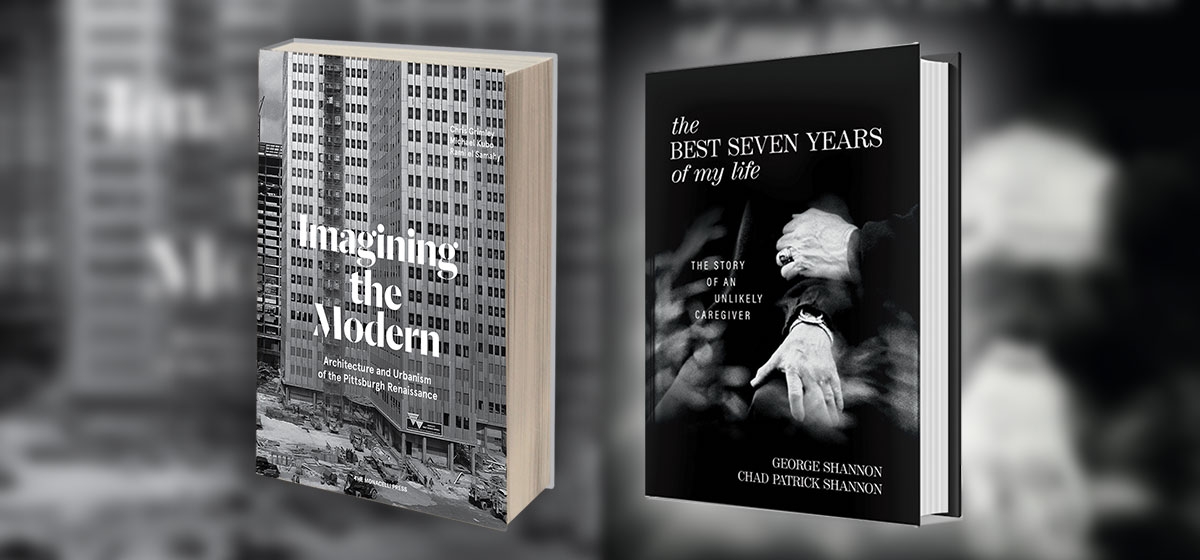

Short Takes: “Imagining the Modern,” “The Best Seven Years of My Life”

“Imagining the Modern” is a gorgeous book about a period that not everyone thinks is beautiful: the postwar design of Pittsburgh. It is a truth universally acknowledged that you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone, and the popular consensus holds that East Liberty, the Hill District and a key part of the North Side were savaged by senseless “urban renewal.” Indeed, the best minds of this generation are at work trying to restore the human scale to these neighborhoods. “Imagining the Modern,” scrupulously factual about the matter, is a valuable collection of stunning visual evidence and dispassionate analysis.

The expertise on display is an extension of an exhibition of the same name at the Heinz Architectural Center at the Carnegie Museum of Art in 2014–15. The concerns of the curators extended to the city’s first Renaissance, the celebrated effort of the powers-that-were that tackled the wretched pollution and rebuilt crumbling infrastructure. “This book explores the manifold ways the modern was imagined in Pittsburgh,” write the three curators. They contend that Pittsburgh was an important national example, both in the style of architecture and the example of bold strokes for a post-industrial era.

“Imagining the Modern” is a treasure trove, a collection of lucid essays, little-known architectural renderings, lush photography, key newspaper articles, interviews with movers/shakers like Tasso Katselas and less famous figures like Troy West, and transcripts of salons held by the Heinz Architectural Center. I especially appreciated the memory nudges, such as the reminder that Robert Moses, the grandiose master planner of New York, had been invited by Howard Heinz in 1939 to create an “arterial plan” for Pittsburgh. As the essay by Kelly Hutzell notes, the basic outlines of his plan came to be the 10th Street Bypass, the Parkway East and Crosstown Boulevard (bisecting Downtown and the Hill District). “Of the third, he said: ‘Incidentally, this will wipe out a slum district [the Lower Hill] that is no credit to Pittsburgh, and which has a depressing effect on available surrounding property.’ ” It was, Hutzell says, “an ominous harbinger of things to come.”

In this self-published memoir that has gained national attention, Sewickley resident George Shannon and his son Chad tell a love story for the ages—and the aging.

George was your typical affluent suburbanite, a hard-charging sales manager who enjoyed a round of golf and a drink with the guys, and who kept his lawn in “impeccable” shape. Sure, he loved his wife, Carol, but he had essentially sleepwalked through the marriage. “In my mind, providing a steady income, a home, a faithful man, and a father to three sons had been enough. If you were grading my obligations as a husband in the traditional sense, I’d have passed,” he says. Yet with the kids grown and retirement looming, “ours had become a boring existence.”

That changed in the spring of 2010. Carol, age 63, had a stroke while on vacation in Mexico. On the tension-filled flight back, George had a realization: “If Carol survived this, I would devote my life to making hers better.” Then she had another stroke. She required constant care and attention. George stepped up to the task “like I had everything else since I was a child: head-on.”

Driven by regret for the years he spent failing to appreciate Carol, George becomes adoring, doting and dutiful. Carol’s health complications continue, but this petite, bookish woman with an easy laugh and a gift for friendship usually defies the worst prognosis and carries on. “I’m fine” is her calm refrain to most every medical episode. She and George have many good years in Sewickley. They dine out, go to the movies and travel when conditions permit. They draw closer to their Catholic faith.

“The Best Seven Years of My Life” has the intimacy of a conversation with a stranger on a cross-country flight, in business class and with complimentary bubbly to accentuate the confessional. Like those freewheeling conversations, there is some inevitable repetition of points, though always in the service of sincerity. You sense how George succeeded in sales. Chad, the lawyer son who crafted the story, has the writing chops to pull it all together.

As Chad said in a recent New York Times profile of his parents, tied to the book, “When the relationship faced its drastic change, my father totally accepted his fate and grew from it. He recognized anew that he was, as he puts it, ‘terribly in love with this woman.’ ”

George and Chad Shannon, as a writing team, drive home a heartfelt message without ever getting preachy. “Marriage didn’t equate to love unless you gave it love” is George’s central insight. While the prime audience for their story will be folks in their golden years, “The Best Seven Years of My Life” might make a good wedding gift—for the groom.