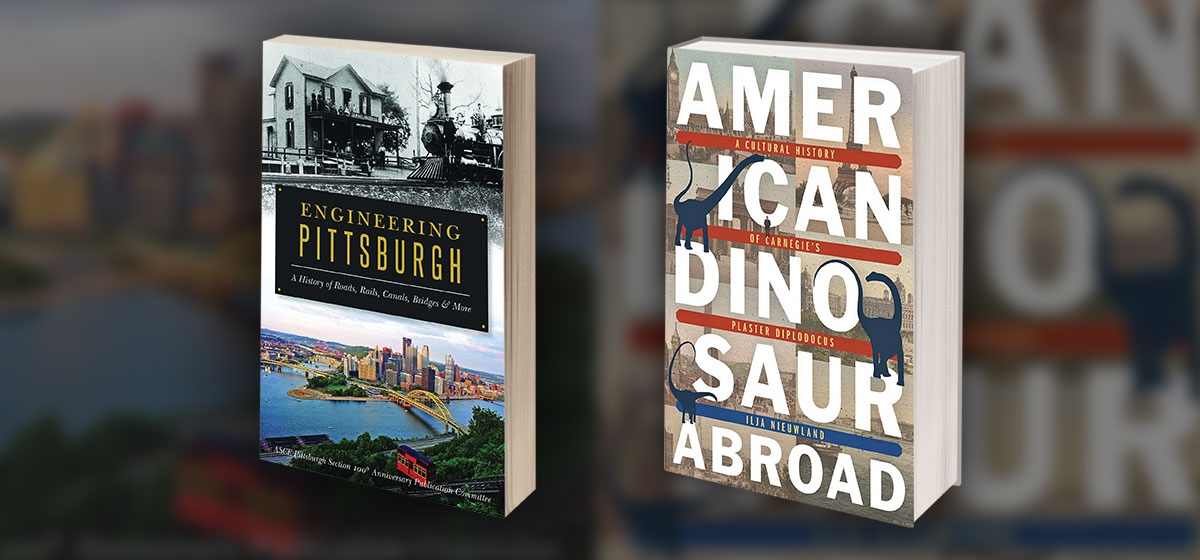

Short Takes: “Engineering Pittsburgh,” “American Dinosaur Abroad”

New selections from Pittsburgh authors

Without civil engineers, our world would fall apart. They are hidden brains behind what we civilians take for granted—all the marvelous methods for getting us from here to there, safe and sound. To observe its 100th anniversary, the Pittsburgh section of the American Society of Engineers has produced an indispensable survey of what has been built around here since, oh, 1681. Helpfully illustrated with maps and lush black-and-white photos, it starts with borders for Pennsylvania’s charter and takes us all the way to Uber’s self-driving vehicles, born out of Carnegie Mellon’s Robotics Institute.

The subtitle promises the history of roads, rails, canals and bridges. The “more” is even longer: the formation of Pennsylvania’s borders, public transportation, airports and aviation, drinking water and wastewater, navigation and flood control. The 16 contributing authors are either professional engineers or communications officers from the field. They have all struck a fine balance, giving the reader detailed information and history but not in excruciating detail. This is the best kind of coffee table book. You can pick up a chapter and read one passage, and find out something you are surprised to know by the time your coffee is finished.

Such as: How many bridges are in the city of Pittsburgh? This popular bar trivia question is answered with precision: 370 … to 700. “The total depends on the specific definition of a ‘bridge,’ ” which might sound like a Bill Clintonian answer, but it’s complicated. It’s 370 by “engineering standards,” and 700 if you count ramps, minor structures less than 20 feet, and other crossings that might be considered bridges to the amateur eye. “Any way you count it,” concludes the writer Todd Wilson, P.E., “there are a lot of bridges.” As I said, this book ends up serving the general audience.

Other various stuff I didn’t know: There used to be a 1 million gallon reservoir Downtown where the Allegheny County Courthouse is located today. (To be fair, “used to be” means 1828, way before Downtown had swank.) The first proposal for the University of Pittsburgh’s main campus building was “an interlocking labyrinth of six-story buildings with a skyscraper at one end.” The architect was one Edward P. Mellon, nephew of Andrew and Richard, who had purchased the land for the school. That inside job was somehow sidelined, and Charles Klauder’s Cathedral of Learning watches over Oakland today. And why did no one ever tell me that my high school, Fox Chapel Area, was the site of an airport, Rodgers Field, from 1924 to 1934? Further, Amelia Earhart once landed there—and foreshadowing a famous Pittsburgh’s characteristic, her plane hit a pothole on the landing field.

“Engineering Pittsburgh” will please civil engineers and those who use their products every day.

We pittsburghers tend to be possessive of our dinosaurs. The collection at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History is either lodged in our childhood memories or fresh from a visit last week with gaping kids in tow. We know that Andrew Carnegie financed the excavation in Wyoming that discovered the famous Diplodocus in 1899, colloquially known as “Dippy” and scientifically called Diplodocus carnegii. We might know that casts of the dinosaur’s bones were made and sent around the world. And that’s usually about enough.

But wait, there’s more. Much more. A Dutch historian of science, Ilja Nieuwland, tells us all about it in “American Dinosaur Abroad,” a fascinating account of the sensation that the dinosaurs caused in London, Paris, Vienna, Berlin and elsewhere. Carnegie, now fully in his philanthropic and change-the-world mode, used his gifts for political and social influence. Royalty and other creme de la creme would always turn out for the unveilings, as happened in London’s Natural History Museum in May 1905. “The aim of bringing him in contact with people of power, and to give him a public forum in which to express the ideas he wanted to convey to them, had been achieved,” Nieuwland writes. “Andrew Carnegie’s Diplodocus gained unprecedented status because of the uses to which it was put and the channels that were used to publicize it.”

Nieuwland, an academic at the Huygens Research Institute in Amsterdam, writes lucidly (and directly in English, which makes a monolingual American green with envy). He provides the cultural history promised in the subtitle, describing how “the age’s lust for the gigantic, the outrageous and the sensational was amply fed by the discovery of the remains of ever-stranger animals in the New World,” and how the emerging media of the day fed the fascination across social strata—and how the fever for dinosaurs was like the “meme” we associate with online phenomena today.

And just to keep us humble, he quotes a German writer with the elaborate name of Gustaf von Dickhuth-Harrach. He visited Pittsburgh in 1907 for the grand opening of the Carnegie Museum, filled with dinosaurs. While the new museum and library were “truly magnificent,” he was less complimentary to our fair city: “The railroad descends from the western mountain slope, and from the valley a sea of dark red flames lights up. It looks like a gruesome vision from Dante’s Divine Comedy. … Should a naïve imagination portray the entrance to hell on earth, he would come up with what could be seen here.” Here’s hoping that the descendants of Herr Dickhuth-Harrach come back to see us now.