Sheryl St. Germain Muses on her Son’s Overdose in “The Small Door of your Death”

According to the National Institute of Health, more than 115 people in the United States die every day from opioid overdoses, adding up to well over 40,000 deaths a year. And while statistics lend a sense of scope to this epidemic, it’s often the tragic aftermath of a single death with its unanswered questions that hits hardest. As an avid consumer of the local paper, it’s not difficult to find the lines “passed unexpectedly” while scanning the obits, a standard euphemism for those who’ve succumbed to a misunderstood mental illness that for me includes former students, co-workers and friends.

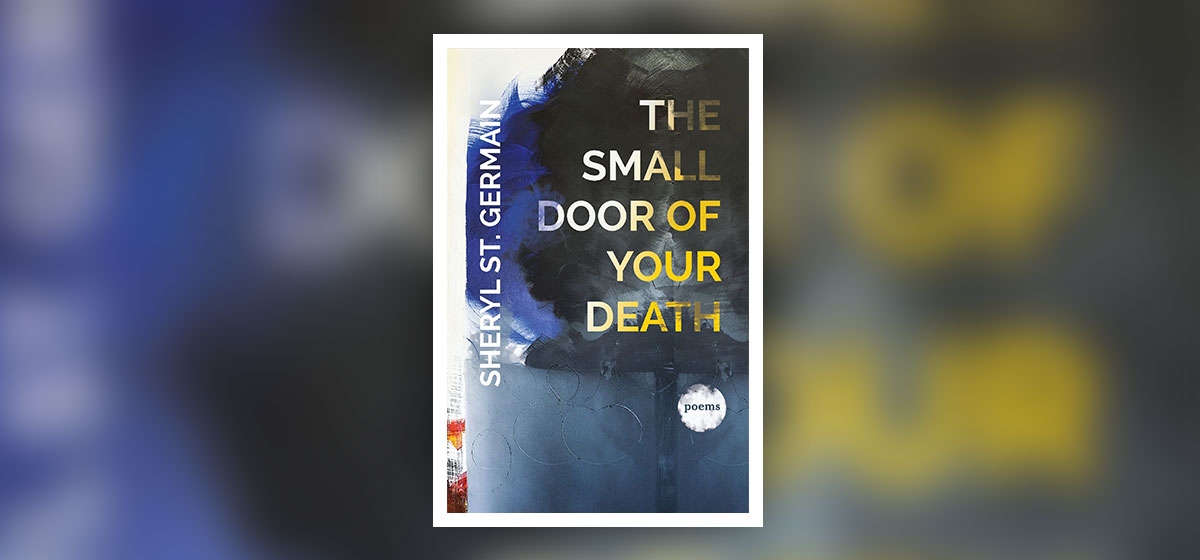

For some, the best way to comprehend the depths of this crisis might not be with clinical science but through the emotional appeals found in newspaper features, documentaries and especially, poetry. One recent standout, “The Small Door of Your Death,” is the latest collection by local poet and New Orleans native Sheryl St. Germain, published by Pittsburgh’s rock-solid Autumn House Press. St. Germain, an award-winning writer and director of the Masters of Fine Arts writing program at Chatham University, uses the book’s 89 pages as a way of coming to terms with the December 2014 overdose death of her only son, Gray St. Germain Gideon. The writing here lingers, full of beauty and pain. And as with so much of St. Germain’s work, it’s the precise language and strong voice that make it soar.

The opener, “Loving an Addict,” lends perspective, the entirety of it reading, “yesterday the skies were troubled/ gusts almost knocked us down// today sun, the kiss of a breeze// it was always fights or lies// maybe at the end// I preferred the lies.” The honesty in the ending juxtaposed with observations on weather set a wearied tone and adds insight into the day-to-day worries of dealing with a loved one’s addiction.

The book also includes needed characterization of the son as both child and adult. In “Son Poem,” he’s presented as having “thin and careless hair,/ strong and directionless, indifferent// to brushes…” In “The Good Mother,” readers get some foreshadowing as she writes of “Ninja Turtles/ stacked like a pile of corpses in the corner,” balancing that with the little boy who “smells like any child/ just out of a bath, fragile and wild.” This gets offset in “Christmas, 2013” where the son is described as “no longer a boy, but a young man/ with eyes that ask to be left alone.” These details, always from the mother’s perspective, allow the son to become rounded and lend emotional resonance.

For longtime readers of St. Germain, it’ll come as no surprise that her family has a history of substance abuse, including her own, that’s been chronicled with much heart in previous books and essays. In “A Perfect Game,” she focuses on her father who died of cirrhosis. The poem reflects on how “he would bowl a perfect game, twelve strikes/ in a row, no matter how much he drank. Somehow// drink and skill merged for a time into the poetry/ of a flawless act. Sometimes we would drive with him// to tournaments far away, fear gripping us as he woozed/ back home, barely avoiding the crashes he would have// in the future.” The poem, full of interesting line breaks and language ends not with anger, but empathy as the speaker emphasizes, “what did I know, of a father’s Stygian alleys,/ of drink’s guttered offices?” The wordplay here feeling observant and transformational.

What makes St. Germain’s work so effective is both its insight and love of language that remains accessible for all readers, not just academics. In “Crook,” she writes of a “word that haunts…/ the old-fashionedness of it.” She continues by ruminating on a “you” that includes “Our son,/ our brother, our friend,” who’s getting involved with theft that often goes with the territory, a necessity “to stay alive/ and high.” The poem is full of playful etymology and street-lingo for the euphoria of drug-use, “cranked, amped, baked, stoned, fried.” Her use of a 2nd person point of view lending itself here to a more objective yet knowing voice.

Personification, or “the representation of an abstract quality in human form,” when used effectively adds figurative depth and perspective to something difficult to qualify. In “The Grief Committee,” St. Germain compares the emotion to “some sort of cleaning woman” who wishes to “wipe our hands of it all,/ empty out every spidery space,” before extending it to a mathematician “doing mathematical proofs and equations/ over and over, if this, then that…/heroin plus benzos equals death.” The poem ends on a more realistic portrayal with “a crazy woman,/ hair unbrushed and matted…/ mad with sorrow.” The style here feels reminiscent of Jeffrey McDaniels’ twisting and often metaphorical work in “The Endarkenment,” a 2008 collection that also wrestles with addiction and it consequence.

In a 2015 piece for the online journal Vox Populi, St. Germain writes in “Essay in Search of a Poem,” of the difficulty “to say the hard truth but to resist the final labeling, the formulation of him sprawling on a pin, wriggling on the wall, defined always by his last mistake. You know poetry is the best way to say two things at once, so you keep trying.” It seems that with “The Small Door of Your Death,” she has succeeded at the difficult beginning of, in her words, “efforts at closure.”