Carol Holmgren lifts a baby bunny—a kit—from its bed at Tamarack Wildlife Center in Saegertown, Crawford County, for morning ministrations that include potty training and breakfast.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”379″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]Just four days old, the tiny Eastern cottontail weighs little more than an ounce and its eyes and ears are still closed. He and three littermates were brought to the center after a garden tiller destroyed their nest and their mother disappeared.

“The homeowner called and we counseled her to move the babies 20 feet away to another part of the yard in the hope the mother would return,” says Holmgren, a licensed wildlife rehabilitator and Tamarack’s executive director. “Unfortunately that didn’t happen, so she brought them here.”

Although rabbits are one of the world’s more ubiquitous creatures, orphaned kits won’t survive without intensive nurturing and expert care.

“When they’re as young as this little tyke, they aren’t able to pee on their own and have to be stimulated or they’ll die,” Holmgren says, as she massages the kit’s anal area with a cotton ball soaked in warm water, mimicking the motions of a mother rabbit’s tongue. The kit’s barely-furred legs twitch in response, as Holmgren coaxes a few drops of urine at first and then a steady stream. “He’s pooping, too. That’s good,” she says, marking a chart. “Makes me happy.”

Holmgren repeats the routine with three different litters before turning her attention to feeding, deftly piping a small amount of neonatal formula into the kit’s belly through a tube. “Beautiful!” she says, when she feels the stomach expand ever so slightly in the palm of her hand.

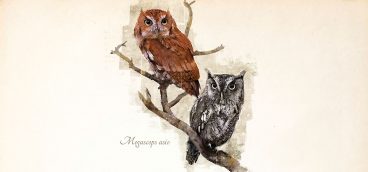

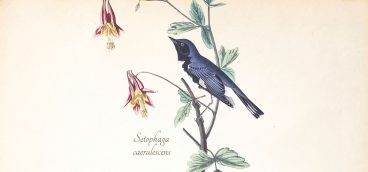

Because rabbits are especially sensitive to stress, their nursery is separate from the rest of the center, which on this day houses a concussed barred owl, a peregrine falcon with a broken wing, and a turkey vulture scheduled for feather implantations, or “imping”—the avian equivalent of a hair weave. Also in residence are an injured robin, a bald eagle receiving chelation therapy for lead poisoning, and a barn owlet being raised for education purposes—which is Tamarack’s other mission.

A day earlier, a 20-pound snapping turtle with a mended shell fracture was discharged into a local lake, and an orphaned great-horned owlet was transported to the Humane Animal Rescue Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Verona for fostering by Martha, an adult member of the species who will teach it to hunt.

With help from a small staff and a team of volunteers, Holmgren manages Tamarack’s ever-changing menagerie. Although she is a raptor specialist who has nursed dozens of hawks, eagles, falcons and owls back to health, Holmgren treats even the smallest sparrow entrusted to Tamarack with reverence. “Every life has value,” she says. “Our taking them in makes a difference to the animal and to the person who brought it here.”

Because the Pennsylvania Game Commission prohibits the fostering of wildlife by non-professionals, centers like Holmgren’s are the only legal and ethical resource for folks who find animals in distress.

Yet, despite a growing need, there are just 45 licensed rehabilitators in Pennsylvania, down from 25 years ago when many still in practice today were first starting out. Training to earn a game commission permit is rigorous, and so, too, is the perpetual fundraising needed to sustain operations, since rehabbers receive no government aid.

“They are a huge asset to us,” says game warden Chris Reidmiller. “Without them, a lot of wildlife wouldn’t have a chance. We just need more of them, and they need more public support.”

But recruiting new members is a challenge, according to Suzanne DeArment, president of the PA Wildlife Rehabilitation and Education Council, because rehab work is uniquely demanding, and not a job but a way of life.

“You won’t last if you’re squeamish about feeding dead mice to hawks, or get grossed-out when a possum poops on you, or freak out when someone brings you a fox dragging a leg trap,” she says. “You see some awful things, and you’re working, sometimes, 24/7. But for those who can do it, rehab is a passion, a labor of love.”

Because only one-third of Pennsylvania counties have a rehab facility, DeArment, of Meadville, retired after 29 years of hands-on care to launch Wildlife in Need Emergency Response of Pennsylvania, a network of volunteers who capture and shuttle mammals, birds and reptiles to rehab centers, including Wildlife Works in Youngwood, Westmoreland County, and Verona’s Humane Animal Rescue (HAR), one of the state’s larger facilities.

In 2019, HAR’s four rehabilitators and cadre of volunteers treated 4,132 patients—double the number of a decade ago and representing 134 different species. Animals have included geese found tangled in fishing line, bats removed from attics, opossums struck by cars, songbirds mauled by feral cats, orphaned raccoons, and an abandoned alligator.

The goal of every rehabilitator is to return mended wildings to their natural habitat, and HAR claims a 65 percent success rate, which is twice the national average. Some patients who don’t recover well enough to survive in the wild are kept as education ambassadors, like Martha, the great horned owl, and three silver foxes seized from a Pittsburgh home by game wardens.

“The game commission asked us to keep them as evidence while their owner was prosecuted,” says HAR’s executive director Dan Rossi, “and when the case was finally closed, they suggested we either euthanize or release them to the wild.”

Knowing they were too habituated to humans to survive on their own, and because, Rossi says, “there was no way we were going to put down such amazing animals,” he opted instead to have a large outdoors enclosure built with watering fountains and tunneling dens where the trio could live out their lives.

Animals also are brought to the center by Good Samaritans, he says, noting that wildlife encounters have become increasingly common as forests and fields are lost to development.

“One of our missions is to help people become more comfortable co-existing with wildlife and to understand what they are finding in their backyards,” says Rossi, who installed a help line in 2019 which answered 3,000 calls its first year.

Even during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic when HAR was limiting admissions, dozens of animals were in various stages of care, including an osprey hatchling that had to be handfed bluegills or trout every four hours, and an orphaned squirrel found by Regent Square resident Cheyenne Schoen.

“I was frantic,” Schoen recalls of her struggle to keep the animal alive while pushing to get him into professional hands. “I was so grateful and relieved when Verona could finally take him because I didn’t want him dying in my care.”

Wildlife Works also was busy in recent months despite the pandemic, or perhaps because of it, since more people were at home to notice things, says founder Beth Shoaf, who, after 29 years, still considers her work a calling.

“I was the crazy animal lover in the family. As a kid, I’d run home crying when my boy cousins stomped anthills; it was so distressing to me. I developed this need to mitigate suffering, to heal the hurt we cause other creatures.”

With community support, her center has grown from a basement hospital and nursery to include a flyway where birds of prey, Shoaf’s specialty, can try out their wings as they recover from traumatic injuries.

Shoaf uses traditional and sometimes alternative therapies to restore a patient’s health. When a golden eagle struck by a train was brought to her with a nerve-damaged leg, she enlisted the help of an acupuncturist as well as a chiropractor who performed spinal and pelvic adjustments. “The bird came in here with a curled-up talon and little by little, over 11 weeks, it came back,” she says. “There are no words to describe how it felt to me on the morning I released her.”

Not all stories end happily, and a hard reality of rehab is dealing with death. In May, Shoaf put down an osprey found shot in the leg in an Indiana County field.

“If an animal comes in too broken to be fixed, I can’t euthanize fast enough,” she says. “It’s a blessing to be able to end the suffering. The toughest cases are those you’ve been treating for so long you’re emotionally invested and yet can’t get to end-stage healing, to where the animal can be released. Those are heartbreaking.”

Most often, the animal is put down as a final act of compassion, she says. “It may be hard for people to understand, but when you love wild animals, you know that a humane death is preferable to life in a cage. Although some animals can be kept for education purposes, not every creature has the temperament to live in captivity, and when you’ve taken away their wildness, you’ve taken away their life. Those of us who do this work are able to judge that and know the difference.”

And the heartbreaks do not deter her. “When there’s a setback, I get back in the saddle and move on to the next case. I’d rather be hauling buckets of duck shit than sitting in front of the boob tube. This is my life’s work, and in some small way I like to think I’m making a difference.”