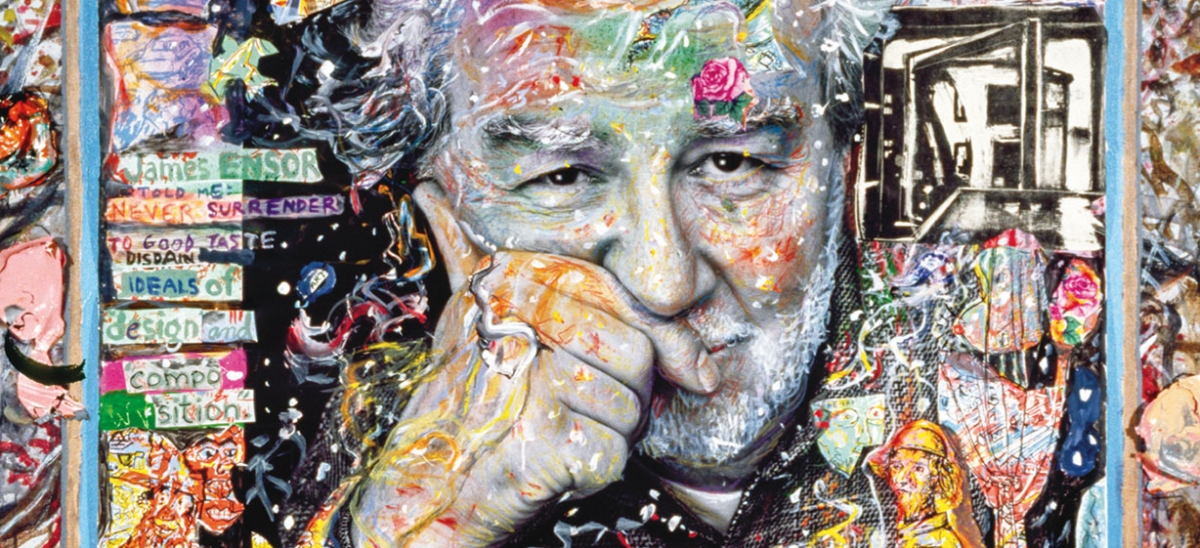

Robert Qualters: When Retrospection Gets Personal

As we get older, as age begins to play tricks with our memories, as our surroundings change and the immediately familiar becomes obliterated, we come to rely on simple strategies like keeping a photograph album or simply hanging on to significant things.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”105″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

Many artists make memory their stock-in-trade, not simply as documentation, but rather by recalibrating it to a higher, more potent level. Pittsburgher Robert Qualters, who has now reached the age of 80, is doing that right now. And he has been doing it since perhaps 1968, when he returned to live in Pittsburgh and found in his native region an inspiration that he continues to rehearse. No painting by Qualters is the same, no painting by Qualters is not immediately recognizable by its style and its sensibility.

Vicky Clark, who has known Qualters for a long time, has written a monograph, “Robert Qualters: Autobiographical Mythologies,” 2013, University of Pittsburgh Press. She is aware of the stigma that until recently used to be attached to “regionalist” painters. I’m not sure that the artist much cares either way about the use of the expression. Clark sees his work in a broader context, and after outlining the course of his professional life… as a student in Pittsburgh (Carnegie Tech, mainly) and later in California (where he studied under the great abstractionist painter Richard Diebenkorn) and teaching at the State University of New York (SUNY), Oswego, N.Y., she concentrates on the influences that inform his work.

There is a moment recorded in the book when Qualters observes, “I steal only from the best,” and, like the best thieves, he steals on his own terms. Other than Diebenkorn, there are the artists he came to know in Pittsburgh, notably the Carnegie Tech crew. Of them the late Robert Lepper, a much underrated artist, looms large (in contrast to Roger Anliker, with whom Qualters had an uncomfortable relationship). Qualters’ rejection of Anliker is a useful indicator of his own character. Clark usefully connects the role of the local Carnegie Museum of Art with Qualters’ sources… as when Samuel Rosenberg’s slightly skewed perspective resonates with Qualters’ almost willful neglect of perspective.

In a sense, the artist’s willfulness shines through in this volume. An early (1938–40) surviving drawing illustrated in the book is tough and knowing, and in 2007 he revisited the work in a robustly painted canvas, “Quite Early.” This painting incorporates other elements from his later paintings, including laddish phallic imagery. Wordsworth’s famous line “The Child is Father of the Man” comes to mind here.

Beyond his immediate experience, Qualters is responsive to the Old Masters, notably Rembrandt, Johannes Vermeer, Pieter Brueghel the Elder (the painting illustrated in the book does not belong to The Carnegie, incidentally, but to the Kunsthistoriches Museum, Vienna) and also to the Modern Masters, especially Pierre Bonnard and Edward Hopper. All these figure graphically in his work, and beyond that, as Clark points out, a whole body of literary texts inscribed into his paintings, drawings and prints add context and heighten the emotional content of the work. She also convincingly includes an important section on Qualters’ collaborative work within the local artistic community.

My own feeling about Qualters is that he is a Magic Realist, extracting from the grimy setting of western Pennsylvania (always recognizable as such) a reconfigured topography, not so much drawn as plastically modeled in two dimensions. To this he brings a sense of brilliant color that seeps out of and around the action he depicts. In a painting owned by The Carnegie, “On the Corner of Craig and Forbes,” 2004, a blind woman struggles to cross the intersection with her dog. She is larger than life, as is her dog, and together they dominate the institutions cursorily painted in as a backdrop—the Carnegie Museum and Carnegie Mellon University. The painting delivers the message that Qualters is an artist for whom the human element is critical. Henry Koerner, Pittsburgh’s best-known Magic Realist, is given a run for his money.

This humanity, this special zest for life, suffuses both his work and his personal life. Clark devotes a full chapter to one painting, “A Life,” 2012, with which, oddly, she begins the book. It is, as the title implies, autobiographical, set out as a board game, where the artist traverses the squares of the board from top left to lower right, each square a little chapter of graphic biography. In 2010, towards the end of the game, his wife, Joanne, dies. (The book is dedicated to her, with a delicate and loving portrait.) By rights, this chapter should have been placed at the end of the book, but Clark is right… it is the key to a life and the key to the book. It is exactly where it should be.

Without memory we would fall apart.