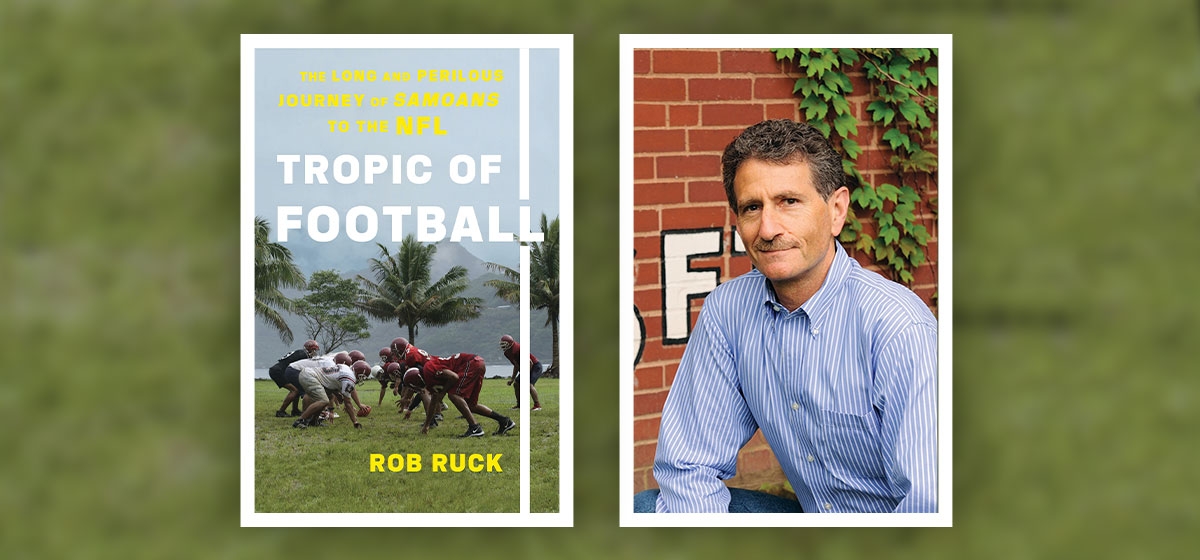

Rob Ruck Examines Football the Samoan Way

The thing to understand about Rob Ruck is that he’s a runner—a distance runner and a daily runner. He’s the type of guy to run the Pittsburgh marathon a bunch of times, and when he is not running, he is at loose ends and out of sync. This devoted runner is also a long-time University of Pittsburgh senior history lecturer and one of America’s premiere sports historians. You can apply the same principle to his writing and research as you can to his running—he needs to be working on something constantly.

Traditionally, Ruck’s sweet spot had been baseball and, more specifically, the Negro Leagues and Latin America baseball, as well as sport in Pittsburgh. Look no further than his two most recent titles for evidence. “Rooney: A Sporting Life” (Nebraska Press), is a biography of the late Steelers owner Art Rooney, that he co-authored with Maggie Jones Patterson and Michael P. Weaver; “Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game” (Beacon Press) is his exploration of MLB’s role in the African-American community in the United States and in the Caribbean. If you want to know about the nexus of sports and community, you could do worse than spending a few hours with one of his books.

With both books in the can, suddenly, there was time, Ruck told Pittsburgh Quarterly over coffee near his office in Oakland. “I was looking for something to do that was different, and out of my comfort zone. And I’ve always been fascinated by athletic excellence—not just the athletic excellence of an individual, but when you see a lot of athletic excellence in one place or with a group of people. I have come to think of those as microcultures of sporting excellence.”

It took him to American Samoa, an island so deep in the South Pacific that it’s closer to Australia than the U.S. mainland, and so small it covers just 77 square miles. In his new book, “Tropic of Football: The Long and Perilous Journey of Samoans to the NFL” (New Press), he does a deep dive into Samoa’s history and unpacks its relationship to football in attempting to understand how the tiny island produces such a disproportionate number of great players.

American Samoa is an unincorporated territory of the United States, one of five such territories (American Samoa, Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands and the Northern Marina Islands) where the Constitution applies only partially. Like PR, American Samoa suffers severe financial hardships and Polynesians islands in general are some of the most hard hit economically. According to the Borgen Project, a Seattle based non-profit studying poverty, 26.9 percent of Samoans live below the national poverty line and only about 30 percent of Samoans aged 15 years or older are employed.

Professional sports often offer a way out of poverty and, as such, can be a real driving force for for football excellence. According to Ruck, participation in youth football pretty much breaks along economic lines across the board, with declining numbers of better off kids participating. It’s a natural fit for Samoa for those reasons. But there’s more to it than that.

”I’ve always been more interested in what sport means to people than the game itself,” Ruck explained. “I’ve come to believe that in these microcultures, places that produce disproportionate numbers of talented athletes per capita—usually there’s a financial incentive, there’s a socio-economic aspect to that, there’s an infrastructure that gets developed—but also there’s usually a backstory of sport having meaning for people, that it matters.”

There are three Samoan players on the polynesian Mt. Rushmore of football—Junior Seau, Jesse Sapaolo and long-time Steeler great and shoe-in for the Hall of Fame, Troy Polamalu. Those players led the way to bigger influxes of islanders. In 2017, there were 30 polynesian players in the NFL, which includes players from Tonga, Independent Samoa, and American Samoa. [Even Guam and Tahiti are represented.] But of those 30 players, 16 were Samoan.

That such a tiny island with such a small population (there are only a quarter million Samoans, give or take, and about a third of them living on the island itself, with the majority living in the United States) has produced and continues to produce so many NFL players was fascinating. The intersection of Samoan culture, history and economic factors with American gridiron ethos is what the book is really about.

”Samoans, particularly in the territory, but even those who are part of the migration… are much more embedded in this culture of Fa’a Samoa, the way of Samoa. It’s a very competitive culture. It’s traditionally a warrior culture. People fight. They fight over land and titles and prestige.”

Beyond the warrior spirit, in order to understand Samoa, Ruck needed to understand the Ainga—the large, multigenerational, extended Samoan family. This has been the center of Samoan life for centuries. Within the Ainga, though, there is fierce competition, and there is also a sense of share and share alike. For instance, they would fight, or at the very least compete, to see who could bring in the most fish. Or bring down the most produce from the hillsides. [This was, until the Cold War, very much a culture dependent on fishing and subsistence agriculture.] But after the competition, the food would be distributed throughout the Ainga as needed.

The Ainga is a key feature of Fa’a Samoa, which is Samoan shorthand for the originating culture of Samoa. Fa’a Samoa, means so many things: respect for elders, love of family, devotion to community, humility and discipline. Fa’a Samoa promotes perseverance and a belief in the value of the collective—that when one member of the team suffers, all the members suffer. It is precisely this kind of thinking that makes a great football player.

But there’s a downside to the devotion, which is the danger of the sport. Kids in Samoa practice hard and long. And, unlike high school football here where live hitting is extremely limited, they hit in practice regularly. It all takes a toll in terms of long-term damage.

The science of CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) and the causal connection to concussive and sub-concussive blows to the head during football practice and games is alarming. The anecdotal evidence is even more harrowing. Samoa’s own Junior Seau killed himself after struggling with CTE following a long, illustrious NFL career. The shockwaves from his death are still felt in Samoa and his hometown of Oceanside, California.

Because of deaths like Seau’s and Pittsburgh’s Mike Webster, the NFL has been in the center of a storm. At the same time, fans, coaches and some players resent and resist any changes to try to make the game safer. Polamalu himself said that he would consider lying in order to clear a concussion test to return to the field, if it came to that.

”They believe that you go all out, you don’t cop to pain—so it’s worrisome,” says Ruck. “It’s very worrisome. What I want to make clear is that there is a downside to sport, coming from my larger republic of play argument. The thing to remember is how important it is to Samoans as a way of developing a story that they tell people about who they are.”