As the curtain rose on the last scene of “The Barber of Seville,” it grazed a table that had been placed too close to the front of the stage. A miniature cannon propped on the table fell with a clang. Everyone in the theater stopped. From his seat in the darkened Benedum Center, Pittsburgh Opera Director Christopher Hahn knit his brow.

It was 10:15 p.m., and the seats were empty, save for Hahn, some lighting technicians and a handful of people milling about with clipboards and headsets. Hahn needed the dress rehearsal to finish on time. Overtime costs for a rehearsal can run $1,000 for an extra 15 minutes for an orchestra alone, and much more for a group of 20 stagehands.

Since the recession began, he and his staff have done whatever they could to avoid these kinds of costs. “I’ve got to decide whether for the good of the show we need to spend the extra $1,000 or not,” Hahn said. But Hahn also wanted the opera to go smoothly when the curtains rose for real, five days hence. The director, Scott Parry, ordered the stage crew to re-do the scene change.

Hahn shifted in his seat. “This is where I get a little agitated, because time is ticking away. But it’s necessary. ”The balancing act Hahn must engage in nightly—eyeing a bottom line while adhering to a mission—is a familiar one to many nonprofit managers. Since the financial meltdown of 2008, state and federal government funding has fallen off, drastically in some cases. Corporate and individual donations have dropped, and foundations have seen their endowment portfolios wither. No one feels particularly rich these days. For nonprofits, the past two years have been an exercise in making do with less and finding new ways to raise money.

For the Opera, like most organizations, that has meant a flurry of hiring and salary freezes. Its budget has been trimmed by almost $1 million since 2008, to $7.2 million. Each production has been honed to a tightly choreographed waltz between economy and craft. A Monday rehearsal, traditionally held at the Benedum, is instead staged at the Pittsburgh Opera’s Strip District rehearsal stage, saving thousands in overtime costs. The productions are chosen with an eye toward cost. Hahn prefers productions that are “light on their feet”—with sets that can be erected and broken down quickly and don’t require extensive lighting rentals. On the Tuesday night rehearsal, the men’s chorus performed the final scene in street clothes to save a few hundred dollars. (The actors get paid while they change out of their costumes.)

The rehearsal finished with eight minutes to spare. So Matthew Worth, the baritone playing the title role in “Barber,” trotted onto stage to rehearse his opening aria, the iconic tongue-trilling solo he performs while putting on shoes and a coat. He had only a few days to nail down the song. And as stagehands took props away, Worth practiced the part as if the house were full.

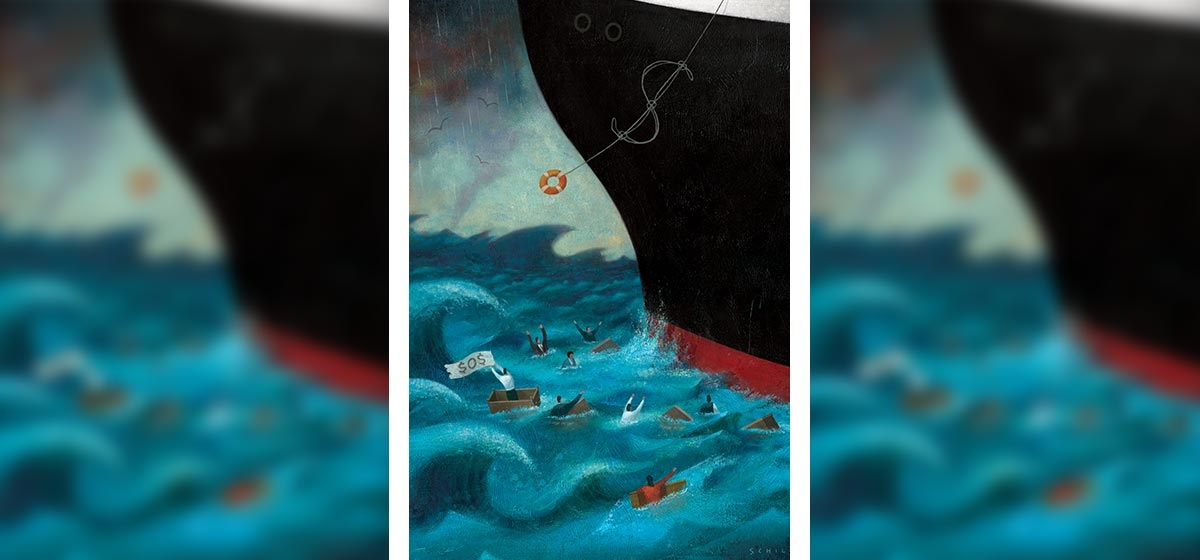

As the recession has squeezed the local economy, so too has it strained the social safety net, manned largely by a web of more than 3,000 local nonprofits. This year, the United Way’s help line saw a 45 percent increase in the number of first-time callers. More people need help with utilities, rental assistance and food. The number of families seeking shelter increased 83 percent over pre-recession levels, according to a survey by the Forbes Funds, which assists local nonprofits.

“There is now a whole new population that is being added to the service delivery system that previously had not been part of the needy population in our community,” said Diana Bucco, president of the Forbes Funds.

At the same time, the revenue streams that support these organizations have waned in the past three years. The majority of funding for nonprofits—about 70 percent—comes from “fee-for-services”: payments for services from private or government sources, such as Medicare or Medicaid; memberships to facilities like community pools; and ticket sales to museums, performances or film screenings. Private contributions—from corporations, individuals and foundations—account for 12 percent of nonprofit funding.

All of these sources have declined in recent years. Governments face major deficits—Harrisburg is looking at a $5 billion hole for 2011. Arts organizations have been hit particularly hard. State appropriations for arts and culture fell 41 percent last year. Ticket sales have dropped. Foundations have had less to give, as have corporations. And individuals worried about their own finances have reduced charitable giving.

So nonprofits, from homeless shelters to theater companies and community health providers, have had to re-think the way they do business. “Nonprofits have been adjusting their business models to a new reality,” said Bucco. “They’ve had to think how they were going to change their business model to meet increasing needs.”

Most have had to find somewhere to cut. The Children’s Institute, which runs a pediatric specialty hospital and a school for special-needs children, eliminated 20 positions (including some through layoffs) from a workforce of 450. Many of those positions were of the back-of-the-house variety—a staff painter, a physician liaison —that the organization decided it could live without. “The recession has really made us make sure we’re operating as efficiently as we can, making sure every dollar gets put to good use,” said CEO David Miles.

The cuts were necessitated by a nearly $1 million reduction in state funds over the last three years. “For an organization with about a $40 million budget, $1 million is a pretty big hit,” Miles said.

Nonprofit cost-cutting is ubiquitous. A recent study by the Robert Morris University Bayer Center for Nonprofit Management found that 82 percent of local nonprofits it surveyed cut back this year, up from 54 percent two years ago and 75 percent last year.

The challenge for nonprofit managers is to ensure they’re not subtracting from their mission. Pressley Ridge, a McCandless-based nonprofit providing foster, education, and social services for developmentally disabled children in several states, had to trim $2 million from its $70 million budget. Most of those cuts came in the form of administrative layoffs.

“We were just figuring out, ‘What can we live without?’” said Susanne Cole, Pressley Ridge’s chief operating officer. “Marketing, new business development, communications—all these things we combed back. We even looked at what type of paper we are using in our printers. We looked for anything we could do to cut back,” without impacting the organization’s services to its clients. “You don’t want to cut your services to kids and families.”

For the Pittsburgh Opera, it was important that any economizing occur backstage. “I’ve tried very hard not to diminish our public offerings,” said Hahn. “We needed to do all the cutting behind the scenes.”

Mergers and strategic partnerships are also on the rise—42 percent of the nonprofits the Bayer Center surveyed this year said they’d looked into one. Merging some part of their operations can bring economies of scale to smaller organizations and allows them to focus on what they do best. The nonprofit group Community Auto, which refurbishes donated vehicles and provides them at free or reduced rates to low-income clients, merged earlier this year with the social service group North Hills Community Outreach. The Northside Common Ministries, a men’s homeless shelter, became an affiliate of Goodwill of Southwestern Pennsylvania, allowing it to tap into the larger organization’s resource base while giving their clients access to all of Goodwill’s employment and housing services.

Some groups have found new sources of income, but even these can come with strings attached. Neighborhood Legal Services Association, which provides low-income people with legal aid in civil matters such as foreclosures, domestic violence cases and employment disputes, saw its donations from foundations and a lawyers’ endowment fund drop during the recession. It has kept its budget fairly level with a federal stimulus grant and a handful of other sources. But these require staff to spend hours aggregating data and writing quarterly reports. The staff work from home on the weekends and after work hours to get the reports finished, said Christine Kirby, director of resource development.

“It’s questionable for us how long we can keep our administrative capacity stretched,” she said. To keep up with the paperwork, the organization has been looking for solutions by partnering with universities, law firms and technology companies.

Many nonprofits have simply had to do less. In August, Pressley Ridge abandoned an in-home autism program because the state had not increased its reimbursement rate for the service in more than a decade, Cole said. The Pittsburgh Irish and Classical Theatre combined several plays into a festival format, and Quantum Theatre has eliminated one play this season.

“What we have told most nonprofits is to go back to your core competency, and whatever your core competency is, do it exceptionally well,” said Bucco, of the Forbes Fund, which provides grants to nonprofits for strategic and business planning. “The other pieces you’ve taken on, find somebody else to do it, rather than taking it on yourself.”

A kind of retreat to bread-and-butter programs at the heart of the mission is not unusual, said Peggy Outon, the executive director of Robert Morris’s Bayer Center. New programs and innovations have fallen off, as many nonprofits simply try to keep the lights on and doors open. “It looks like people are pretty much hunkering down, and they’re not thinking in an innovative fashion. In some ways, they can’t afford to think like that. There’s not enough hours in the day.”

Nonprofits have had to shelve expensive long-term projects. In the summer of 2008, Eric Mann, executive director of the YMCA of Greater Pittsburgh, kicked off a $30 million capital campaign to build a new facility in the South Hills. By that fall, the stock market was in a freefall. Mann’s capital campaign committee—mostly business people and lawyers who could ask their friends to write a check toward the building fund—made it clear they weren’t going to raise that $30 million any time soon. As Mann said, “I remember, it was pretty clear that we needed to slow things down.”

Don Rhoten, the executive director of the Western Pennsylvania School for the Deaf, had a similar realization. “When the stock market was in the 6,000s, you had to think, ‘where are we going with this?’ You realized that life as we knew it had changed.”

Rhoten’s school went on an aggressive remodeling campaign in the ’90s and ’00s, renovating classrooms, its library and learning center, and a myriad of other amenities for its students. Rhoten wanted to air-condition a cafeteria and dormitory and put in a geothermal unit to raise the Edgewood school’s green credentials.

The school’s historic main building uses some equally historic radiators, which bake some rooms and leave others frosty in the winter. But raising money for heating and cooling is unlikely in today’s economic climate, he said. “Most foundations are not interested in having their plaque on a radiator.”

Rhoten has been busy doing something that a lot of nonprofit managers have been doing these days—making new friends. The thinking goes, if your organization’s friends aren’t giving as much as they used to, make new ones. (But keep the old, of course.) He has been using fundraising events such as a bike ride, a clay-pigeon-shooting event and a golf tournament to try to introduce potential “friends” to the school. “To stay alive, you’ve got to keep meeting new people and making new friends.”

Across the board, nonprofits have been asking for more money from big donors, asking little donors to become big donors, and asking those who’ve never donated to give what they can.

Especially during an economic downturn, keeping the fundraising fires burning is important, said the YMCA’s Mann. Though the Y tempered its own fundraising goals, the organization continued to make progress toward its capital campaign. “We stayed with it and worked with it and stayed patient because we knew (the giving) was going to come back. I’d say, ‘never let a recession ruin a good plan.’ ”

The Children’s Institute’s Miles spends more time now on the phone and over lunch with potential donors talking up what he calls the organization’s “unique value proposition.” To make up for tighter funding from other revenue streams, the organization recently tripled its own fundraising goal to $4.5 million per year.

“It takes a lot of time and effort, and energy,” said Miles. Like many nonprofit CEOs, Miles believes his best fundraising tool is bringing donors to see where their money will go. “If I can get a person to come in and see what’s going on here, chances are I can get them to open their pocketbooks.”

The proliferation of fundraising isn’t confined to big-money donors. The Pittsburgh Foundation has instituted Pittsburgh Cares, a one-day event in which any donations individuals make to a selected nonprofit can be matched by a pot of $500,000. The October event raised more than $3 million for area nonprofits. Pressley Ridge raised over $100,000 from its employees, through a voluntary program that deducts a small percentage from their paychecks.

All of this asking is undoubtedly stretching the communication abilities of nonprofits, Outon said. “Now you’re talking about going to the general public, who’s also feeling the pinch, and asking them for money,” Outon said. It’s a little like asking a cabinetmaker to master forestry. They can learn it, but it may take some time. “It’s a different way of thinking than the way you think when you’re talking to a grantmaker. It’s much less labor-intensive if you can write one foundation proposal and raise $150,000, than raising $150,000 from individuals.”

For all of the economic struggles of the past couple of years, Americans still give more than $3 billion to charity, which is close to the all-time high set in 2007. Some nonprofits, especially those serving the most needy, have actually raised more money during the recession. The Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, which supplies pantries, shelters and soup kitchens across an 11-county region, has served an average of 2,500 new families a month since the beginning of the recession. The organization has increased its budget by $2 million, to $14 million. Much of that came from an emergency food program paid with stimulus money. But foundations and individuals have also increased their support, said executive director Joyce Rothermel. “People who have given are giving more than in the past.”

After a week of rehearsals, Christopher Hahn was back at the Benedum Center. It was opening night for “The Barber of Seville.” The Wednesday rehearsal finished with 10 seconds to spare. Hahn was glad he didn’t have to decide whether to go into overtime. The South African-born Hahn stood in the lobby, in black tie, smiling. He greeted patrons, board members and donors. “The Barber of Seville,” written nearly 200 years ago by a 23-year-old Rossini, is a timeless crowd pleaser. “No one dies in this one,” he said, before giving pecks on the cheek to a pair of ladies in gowns. “It seemed the right time to open the season with something that would make people laugh.” In a few moments, the theater would darken, and Worth and his fellow actors would amuse the audience with the opera’s playful libretto.

Hahn thinks it’s ironic that just when nonprofits are needed most, it’s become increasingly hard to pay for them. The job of the opera, he said, is to take the audience’s mind off the crisis du jour. “Our art form is something people want to be moved by. They want to be inspired and enriched. It’s our job, as nonprofits, to tough it out during hard times.”