Recalling Poet Muriel Rukeyser and her Work on the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel Disaster

When she was just 23, poet Muriel Rukeyser drove from her home in New York City to the hollers of West Virginia, fueled by a desire to investigate and document the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel mining disaster. By the time she arrived in 1936, many of the men who had dug the tunnel were dead. More were gravely ill and would later die.

Six years earlier, on March 31, 1930, Union Carbide and The New Kanawha Power Company broke ground for the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel in Gauley Bridge, WVa. By the time the tunnel opened in 1934, there were reports of miners dead and dying from acute silicosis developed while working the dig.

Silicosis develops when silica dust lodges in the lungs. It fills the lungs, making ordinary lung function difficult—just walking across the room is exhausting. Eventually, as silicosis progresses, the lungs lose all elasticity. Even by the standards of the early 1930’s, conditions at Hawk’s Nest were atrocious. Safety precautions—wetting the rock face to minimize the dust or waiting between shifts for the dust to settle—were ignored or otherwise evaded. The men inhaled the fine white dust every minute of every shift worked.

In all, 764 men who worked Hawk’s Nest died of silicosis.

Rukeyser walked the area and spoke to the people. She documented her findings in a lyric poem which weaves together the many stories told to her by survivors and the bereaved, along with her own account of the area, a sort of naturalist’s elegiac cartography.

The poem is not a snapshot of the disaster, but rather a series of snapshots capturing Gauley Bridge and Hawk’s Nest in different moments: the miner’s camp, the tunnel, the homes of the bereaved and the ill, gatherings of survivors who were advocating for justice, and Congressional hearings.

“When the blast went off the boss would call out, Come, let’s go back,

when that heavy loaded blast went white, Come, let’s go back,

telling us hurry, hurry, into the falling rocks and muck.

The water they would bring had dust in it, our drinking water,

the camps and their groves were colored with the dust,

we cleaned our clothes in the groves, but we always had the dust.”

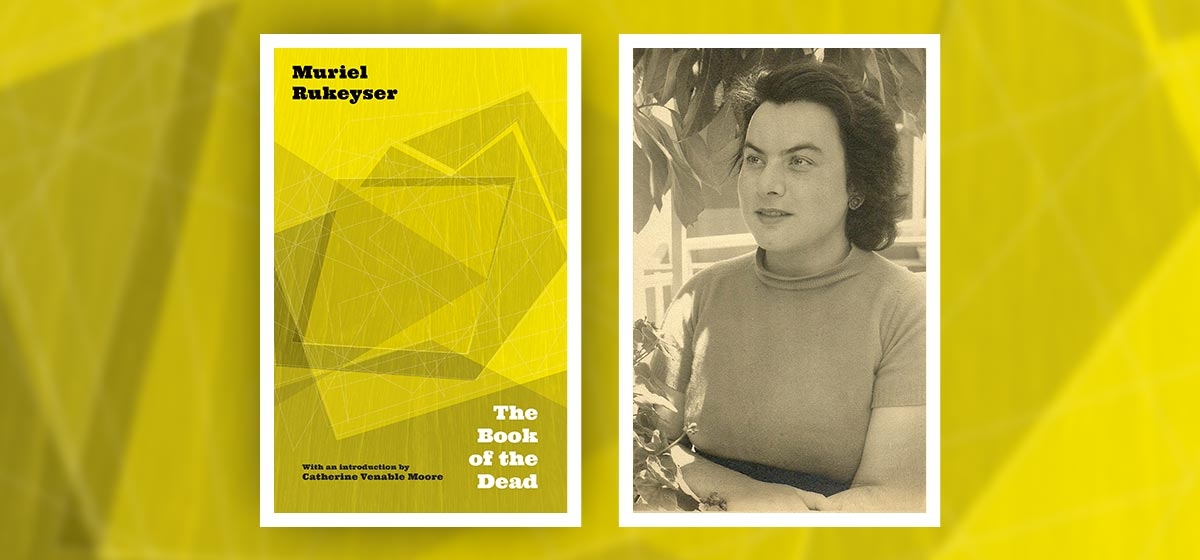

Rukeyser, who died in 1980, first published this poem in 1938 and titled it after a collection of ancient Egyptian spells to assist the dead in the next plane, “The Book of the Dead.” It was re-released this spring by West Virginia University Press. As an introduction, WVU has included a poignant essay by writer, documentarian and West Virginia native Catherine Venable Moore, also titled “The Book of the Dead,” previously published by Oxford American Magazine.

“[I]t is really the most complete document we have of Hawk’s Nest Tunnel and Gauley Bridge and the disaster, which is commonly understood to be the worst industrial disaster in American history,” says Derek Krissoff at WVU Press. “So you have this unusual case where it’s really a poet who was there, on the ground, more or less as it’s happening, who is able to capture it and document it in this very artistic and vivid way. And that stands as the best kind of narrative we have of it.”

Venable Moore described her essay re-examining Hawk’s Nest at a recent lecture: “When I discovered it, it took my breath away. It propelled me forward into this research. I moved back to West Virginia about seven or eight years ago and started exploring some of the spaces that Muriel describes in her poems.” She said her work is a meditation on Rukeyser’s poem, but also on Appalachia, suffering and, race. “The Jones family, who lost three brothers and a father, all within a couple of years to silicosis—their lungs were preserved in these huge glass jars by a doctor who was performing autopsies and were dumped into a dump behind my house. I would go searching for these lungs, trying to find the lungs of the Jones boys. It was just woven into my Saturday night in the country, I guess.”

Though it’s been more than 80 years since Hawk’s Nest, there has been a conspicuous rise in the cases of black lung in the 21st century, according to a recent National Public Radio study. Black lung is really shorthand for the multiple disease processes that mining dusts cause. Silicosis, coal workers pneumoconiosis (CWP) and progressive massive fibrosis (PMF) are all commonly referred to as Black Lung. NPR collected data from clinics in Appalachia indicating that there have been nearly 2,000 cases of black lung in the past 15 years. In response, Congress passed increased funding for Black Lung clinics as part of an omnibus spending bill in late-March.

In certain respects, what happened at Hawk’s Nest is an essential part of the story of capitalism in Appalachia. There is the need to extract energy from the area in order to power the nation, to build infrastructure and fuel this economy. When we think of Appalachia, we don’t often think African-American, but there is a rich African-American culture and history here, including descendants of the Hawk’s Nest men, as many of those who worked the dig were migrants from deeper south who lived in temporary housing in Gauley Bridge.

Hawk’s Nest is infamous among miners and to this day, the term is shorthand for an especially dangerous mine, one where dust regulations are cheated and speed is valued over safety. Big Branch in Raleigh County, West Virginia, was known as a “Hawk’s Nest” mine long before it blew up in 2010, killing 29 miners.

Mounting health and environmental concerns and the sudden spotlight on Appalachia in the Trump era, all make Rukeyser’s work particularly timely.