Public Theater’s Cinematic “An Enemy of the People”

I have always loved the fact that, as a young man, James Joyce was so enamored of Henrik Ibsen that he learned Dano-Norwegian to read the playwright in his native language. And Joyce’s self-proclaimed first mature work, a play ironically called “A Brilliant Career,” was the story of a doctor battling the pestilence infecting a small town, which is essentially the plot of Ibsen’s “An Enemy of the People” written in 1884.

In this 2024 adaptation by Amy Herzog, presented by Pittsburgh Public Theater, we get a version of the original play, but with fewer characters, and some of Ibsen’s more extreme views, if I may adumbrate, watered down. However, the post-modernist staging by director Marya Sea Kaminski adds a fresh dimension which compensates for much of this dilution. Her style is like a good Bugs Bunny cartoon in which the sophisticated aspects are salient to those inclined to notice them but are not vital to those who don’t. More on this below.

Chelsea M. Warren’s set utilizes a thrust stage set at an oblique angle – a clear sign that something is off in the world of this small Norwegian town that we are about to enter. As the action centers on the fate of a spa and baths located here, the set contains water on both sides, which may or may not be polluted with harmful chemicals leached by tanning factories located nearby. It’s a proto-Erin Brockovich scenario, with the town’s ethical doctor, Thomas Stockmann (MJ Sieber), having discovered this contamination, pitted against the nefarious interests of those who benefit financially from the continued operation of the ultimately toxic spa.

Complicating this is the fraternal rivalry of Dr. Stockmann with his brother Peter (Scott Giguere), the mayor of the town who, in the original play, is initially much more antagonistic towards his brother than as depicted here. Ibsen framed this as a Cain and Able conflict. We still see this acrimony develop later in the Herzog retelling; however, it’s not as baked in, and hence less ruthless than the 1884 version.

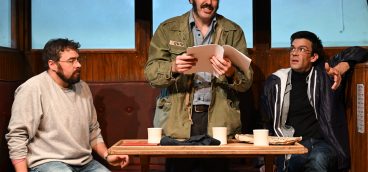

To the credit of the casting process, Messrs. Sieber and Giguere actually look like they could be brothers — something that rarely happens in film or stage productions — which heightens the believability of their conflict. We know how obstreperous sibling rivalries can be, and these two embody it physically as well as emotionally.

This version also eliminates the character of Mrs. Stockmann — making her deceased –which is unfortunate, as she’s the only soul in the original work who changes for the better, as she comes to understand and value her husband’s ethical stand, while nearly all the townspeople devolve from respecting, to despising him, the more he stands against the injustice of the pollution he discovers.

But perhaps the most fascinating and successful aspects of this production are the cinematic conceits explored by Ms. Sea Kaminski, the director, specifically in how she deals with time. She utilizes multiple “freeze-frame” moments, when the cast is frozen in tableaux, emphasizing the impact of key turns in the action. Even more compelling, however, she leaves exiting characters around the stage, still visible to the audience, in some cases sitting passively, in others engaged in some small task before them like reading — thus achieving a duality of time, as if we can peer into hidden moments of their lives that move in a slower pace than the proceedings on stage. The director Martin Scorsese does this, for example, during the climax of his 1973 film “Mean Streets,” when he cuts suddenly to minor characters from earlier in the story existing passively in their lives watching TV, washing their hands, or having a cup of coffee.

A character sitting in view of the audience but exogenous to the action creates a disparity of temporal perception: are we to believe their time or the stage’s? This constant dichotomy underscores the existential division of the play itself: do the townspeople believe the good doctor, or the corrupt mayor? With so much money at stake, you can guess which way the citizens go, and hence, the only person with any integrity is declared an enemy of the people.

The great French film critic André Bazin called such disparities an opportunity for “the democracy of the eye” in that viewers can choose what they want to watch. That Ms. Sea Kaminski achieves this cinematic technique in a live, stage setting is as remarkable as it is engaging.

Ironically, Dr. Stockmann, in Ibsen’s telling, actually becomes an enemy of democracy, declaring, “The most dangerous enemies to truth and freedom among us are the solid majority.” This could be a line from Plato (e.g. “The many are not competent to judge matters of virtue”), making Stockmann’s imperious morality sound like a kind of madness, as he concludes, “All those who live a lie should be eradicated like vermin.” However, this damning pronouncement is not fully realized in Ms. Herzog’s adaptation, as she offers the more anodyne, “I have devoted my life to science and I have certain expertise, certain knowledge, that you, the majority, do not have.” Her dialogue sounds more like a made-for-TV movie than language that compelled one of the greatest writers of the 20th-century to learn a foreign tongue to read it.

Among the outstanding performances are those of Mr. Sieber as the increasingly resolute Dr. Stockmann, who is convincing in his unrelenting naiveté as to his neighbors’ pathological greed, and Mr. Giguere as his brother and unrelenting nemesis. Sam Lothard is especially poignant as the sympathetic Captain Horster, ostensibly the only other honorable man in the town, who’s benign gravitas counters the hostility of the other citizens. Zanny Laird is Dr. Stockmann’s daughter Petra, who sings with an Ophelia-like innocence, and loyally comforts her father. Brett Mack imbues the turncoat editor Hovstad with reptilian insouciance, and in a similar manner Garbie Dukes embodies the unctuous Aslaksen with the kind of false pride projected by corrupt religious leaders. Also compelling are Martin Giles and Evan Vines, who play Morten Kiil and Billing respectively.

The ending of Ibsen’s original play is darker than this version, and his famous line “The strongest man in the world is he who stands alone,” is replaced with, “We just have to imagine, that the water will be clean and safe and the truth will be valued…We just have to imagine…” which sounds like something Scarlett O’Hara might blurt out. See this play for the charismatic direction and the acuity of the acting, but if you’re going to read the playscript, stick to the original version. Ibsen can’t be improved upon. Just ask James Joyce.

AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE continues through February 22nd at the O’Reilly Theater, Downtown. www.ppt.org or 412-316-1600.