Poetic Mission

With its deep pool of talented writers, Pittsburgh punches well above small-city status, especially among poetry circles. Reasons for this embarrassment of riches include the exposure many local poets receive for work that wins them awards, ample workshops, university writing programs with strong reputations and a vibrant scene that features readings nearly every night of the week. Poetry with regional ties has never been more popular and new releases are always on the horizon.

Publishing with a small press can be a mark of distinction for writers in a genre where little money is to be made. One significant contributor to bookshelves both national and local is Main Street Rag, a Charlotte, N.C. publishing house started by Bethel Park High School graduate M. Scott Douglass that has published many Pittsburgh poets.

Douglass said he was drawn to language at an early age by seeking “manly”-sounding lines by the likes of Emerson in the anthology, “A Treasury of the Familiar.” From there, he experimented with sappy love poems in fourth-grade before taking his work more seriously and becoming part of his school’s literary magazine.

He attended Pennsylvania State University-Behrend but didn’t finish. He went back to school in his 30’s and earned a graphic arts degree from Central Piedmont Community College in Charlotte, where he started Main Street Rag as a literary magazine, getting hundreds of submissions a month.

Douglass grew tired of his day job in dental technology after 22 years. His wife helped nudge him to make the transition, telling him, “I think you’re going to have to find something else to do with your time if we’re going to stay together.” With a catalog of hundreds of titles, the career move seems to have been worthwhile.

Like most small-presses, Main Street Rag publishes the work of select poets, but marketing rests mostly with the authors, who often stage readings to promote their work. Both writing and publishing poetry is a labor of love, often with little remuneration.

Why does Main Street Rag publish so many Pittsburgh poets? “It’s rich area for poetry,” Douglass said. “But, I think a lot of it is people like Michael Wurster and others who sponsor reading series; teachers with students. They bring poets together. The poets see what we’ve done for them and seek Main Street Rag out. I’m not consciously saying, ‘Hey, this is a Pittsburgher, gotta publish them.’ They usually find me first. After that—regardless of whether they get their manuscript to me through contest or non-contest, it has to earn its way onto our label. An editor has to select it and that editor is not always me.”

Of all the qualities he looks for in a manuscript, the author’s voice is the most important. “Most of us mimic our literary (or musical) favorites, but keeping your own voice in a field where everyone’s work is rooted in the success of others’ makes it hard. Emerson said: ‘It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.’ That’s what I’m looking for foremost.”

With that in mind, here are some thoughts on a few recent Main Street Rag titles with local ties.

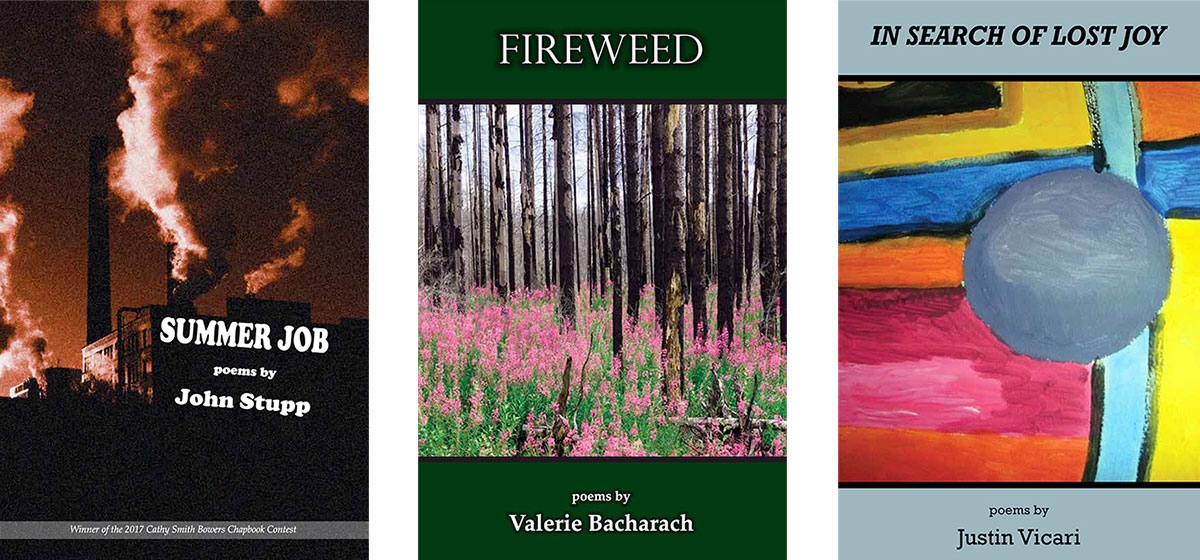

John Stupp has emerged as one of my favorite local voices. In “Summer Job,” a recent work and winner of the Cathy Smith Bowers Chapbook Contest, the Sewickley resident focuses on his speaker’s work at a Ford Motors plant “as big as a city” outside of Cleveland in the late 1960’s. The poems are necessarily reminiscent of Phillip Levine and James Wright, with an innocent being baptized by fire and becoming reflective because of it. In “A Flower Once,” he writes, “it was not the prettiest flower/ but yellow/ for a minute/ it stood out/ brighter than a furnace/ before the petals tore off/ I was the one who noticed/ I was the one not concentrating/ on the job at hand/ on the cores moving in front of me/ lift and stack/ lift and stack/ I was young/ my arms were tired…” With a setting often focused on “the hot ether of foundry hell” and a cast of characters immortalized in poems like “Bob,” “Helmut,” and “Hard Work,” the collection is a standout not just for its profanely accurate descriptions, but also its figurative language. In one example, a foreman characterizes Stupp’s well-intentioned greenhorn of a speaker as “a bad blade on a lawn mower/ no matter how many times I crossed/ the grass wouldn’t be right/ you have a gift…”

In Valerie Bacharach’s debut, “Fireweed,” her speaker is left picking up the pieces of her family life after the overdose death of her son. It’s a subject matter that too many are familiar with as Bacharach nails the range of emotions that go along with loving someone who succumbs to addiction. In “The Last Day,” she writes, “We do not let him into our home.// I take him to lunch at Panera. He whispers/ of a new start, a move to another state, a job with a friend./ he moves so close I feel the warmth of his body.// I’m so tired. I wish he would disappear.” The poignant irony of the lines here emblematic of both Bacharach’s straightforward writing and the necessary grief and guilt survivors are often left with.

Poems such as “Psalm 34,” “Ave Maria,” and “Lamentations,” are reflections of tangible things left in the wake of the son’s passing. This poetry of things, not ideas, is best expressed in “Death, Cataloged,” where she writes of “1 heavy-wool jacket,/ the hard slap of black./ Metal buttons, empty sleeves…// A tuneless guitar, a forlorn snowboard…//A tiny stuffed dog, white plushness worn to fragile cotton./ 4 Dr. Seuss books.” The list-like lines offer readers something more than the abstractions of grief. The objects allow the poem to become grounded and meditative as it is in much of the collection.

Lastly, Pittsburgher Justin Vicari’s “In Search of Lost Joy” highlights the Main Street Rag’s ethos of publishing a wide range of writing with this collection focusing heavily on themes of sexuality. Poems like “Another Body,” “Southern Man,” and “Head in the River” range from the speaker’s closeted youth to the joys of romantic intimacy, evoking a rich physical and emotional landscape. A favorite, “I Just Wanna Be Your Everything,” finds the speaker reflecting on an Andy Gibb TV performance where he says, “For the first time,/ I knew what I was: lonely/ suburban kid in love with a boy-god./ Who can be anyone’s anything,/ let alone someone’s everything?/ Who can do this love thing right?” Vicari’s honesty here and throughout the book runs parallel to the strengths M. Scott Douglass offers readers: genuine voices full of life and experience.