Pittsburgh’s First Great Hockey Rivalry: The Needle and the Great Wall

In the 1950s, the Pittsburgh Steelers and Cleveland Browns were well on the road to what eventually became known and celebrated as the Turnpike Rivalry. But that wasn’t the only rivalry at that time between sports teams from Pittsburgh and Cleveland. While Pittsburgh sports fans were in the early stages of hating the Cleveland Browns, they already had reason to hate the Cleveland Barons, the Pittsburgh Hornets’ chief rival in the early 1950s for hockey supremacy in the American Hockey League.

Long before Mario Lemeiux and Sidney Crosby led the Penguins to Stanley Cup championships, Pittsburgh played a major role in the early history of professional hockey, and, by 1925, gained a franchise in the National Hockey League. The Pittsburgh Pirates, playing in a dilapidated and undersized Duquesne Gardens that was a streetcar barn before it was converted into a skating rink, struggled financially and at the end of the 1929–30 season left town and became the Philadelphia Quakers.

For the 1935–36 season, theatre magnate John Harris bought the Detroit Olympics, a Detroit Red Wings affiliate in the minor-league American Hockey League, and moved the franchise to Pittsburgh. Renamed the Hornets, the team struggled in its early years until it switched its affiliation in 1945 to the NHL Toronto Maple Leafs.

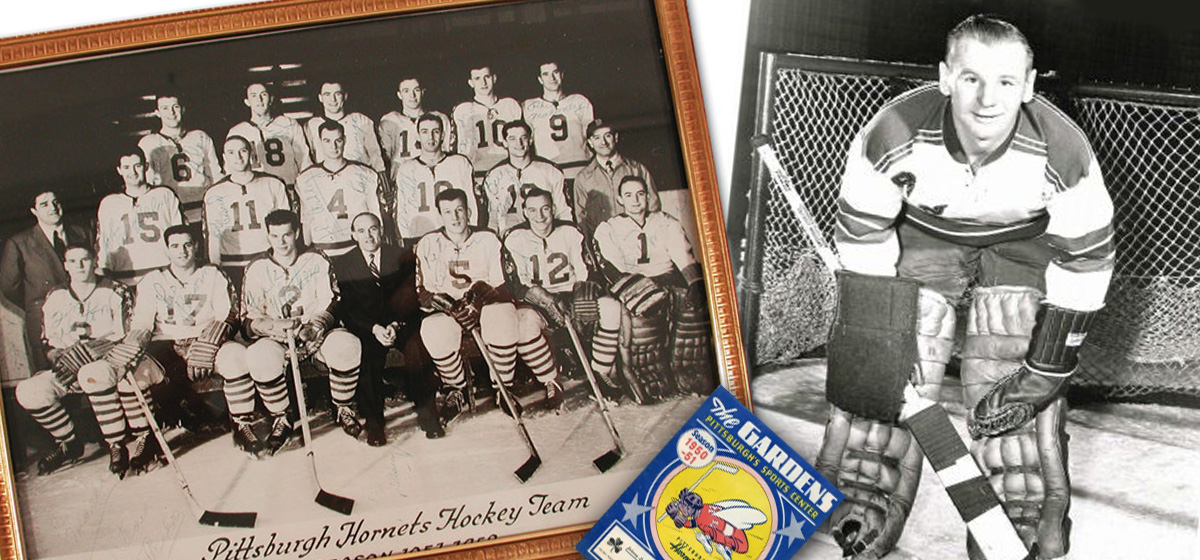

With the help of future and fading Maple Leaf stars, the Hornets became an AHL power in the early 1950s, playing in four Calder Cup finals from 1951–55. During those championship seasons, the Hornets sent future NHL Hall-of-Famers George Armstrong and Tim Horton to the Toronto Maple Leafs, while fading NHL veterans like Howie Meeker and Wild Bill Ezinicki helped the Hornets to championship seasons.

Though they never went on to stardom in the NHL, the Hornets had future AHL Hall-of-Famers in Wille Marshall, the greatest scorer in AHL history, Frank Mathers, one of the league’s greatest defensemen, and Gil “the Needle” Mayer, whose duels with Cleveland Barons goalie Johnny Bowers, the winningest goalie in AHL history, became the focal point for the rivalry.

Called “the Needle” because of his 5 foot 6, 135-pound frame, Gil Mayer made his debut with the Hornets in 1949 after popular goalie “Baz” Basien lost part of his sight when he was struck in the eye by a hockey puck fired on goal. Mayer, who wore number “0” to signify his uncanny goal-keeping skill became an instant success with the Hornets and, in the 1950–51 season, won his first of five Holmes trophies, awarded by the AHL for the fewest goals allowed.

Mayer’s success, however, was more than matched by the Cleveland Barons’ veteran goalie Johnny Bower, dubbed “the Great Wall of China” by sportswriters for his goaltending prowess. Bower had led the Barons to a Calder Cup title in 1950 and had the Barons back in the Calder Cup final in 1951 against the Hornets. The series became a showcase for the goal tending of Mayer and Bower, but, with the series tied at 3-3 , Bower outplayed Mayer in a 3-1 Barons’ victory in the deciding game to give Cleveland its second consecutive Calder Cup title.

The following season the Hornets, coached by hockey legend King Clancy, played their way back into the Calder Cup final, but this time faced the Providence Reds. Leading 3-2 in games, the Hornets won their first Calder Cup in their 16-year history with a dramatic double overtime 3-2 victory on a goal by Ray Hannigan. The 1952 AHL championship was particularly gratifying for Baz Bastien, who was the team’s business manager at the time, and Clancy, who was promoted to coach the Maple Leafs

The Hornets returned to the Calder Cup final in 1953 and had the opportunity to defend its title and, at the same time, exact a measure of revenge for their loss in 1951 to their nemesis, the Cleveland Barons. With Gil Mayer and Johnny Bower playing brilliantly in goal, the series, tied at 3-3, came down to a seventh and deciding came in Cleveland.

Both Mayer and Bower were unbeatable in regulation time and sent the championship game into overtime, tied at 0-0. In one of the most heartbreaking moments in Pittsburgh sports history, Cleveland Barons defenseman, Bob Chrystal, flipped the puck from center ice into Hornets territory. When Gil Mayer skated out of the net to corral the puck, it took an odd bounce away from Mayer and into the Hornet’s net to give the Barons a stunning 1-0 victory and the Calder Cup championship.

Gil Mayer and Johnny Bower would face each other again in the regular season, but would never meet again in a Calder Cup final. The following season the Barons met the Hershey Bears in the Calder Cup final and defeated the Bears 4-2 for their second consecutive title and their fourth in five seasons. In the 1954-1955 season, the Hornets, coached by Howie Meeker, returned to the Calder Cup final and defeated the Buffalo Bisons 4-2 for their second Calder Cup championship.

After defeating the Bisons, Howie Meeker, who had duplicated King Clancy’s feat of winning a Calder Cup in his first season coaching the Hornets, praised his players and “hoped we can do it again.” In 1956, however, the Hornets failed to make it back to the Calder Cup in what turned out to be their last season in the AHL for five years when the city, as part of its ongoing Renaissance, tore down the Duquesne Gardens to make room for the Plaza Park Apartments and a Stouffer’s restaurant.

When the Hornets left Pittsburgh after the 1955–56 season, their star players, including Gil Mayer, signed on with the Hershey Bears and led the Bears to two AHL championships. While Mayer, despite his brilliant years in the AHL played only a handful of games in the NHL with the Toronto Maple Leafs, his arch-rival Johnny Bowers, after leading the Barons to another AHL championship in 1957, was drafted by the Maple Leafs and led them to four Stanley Cup championships. At the time of his retirement at the age of 46, Bower was the oldest goalie in NHL history and headed for the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Once the construction of the Civic Arena was completed, the Hornets returned to Pittsburgh in 1961, and, under the leadership of Baz Bastien, won another Calder Cup in 1965. After the 1966–67 season, the Hornets ended a history that dated back to the 1930s when the NHL underwent a major expansion that included the Pittsburgh Penguins.

After struggling in their early years, the Penguins finally won the Stanley Cup in 1991. In one of the ghostly ironies of hockey history, the Penguins won their first Stanley Cup by defeating the Minnesota North Stars, an NHL franchise that had merged with the Cleveland Barons in 1976, when the Barons folded after only two years in the NHL. Over 25 years after he lost to the Barons on a freakish goal, the Hornet’s Gil Mayer finally had his revenge.