In honor of the midsummer classic’s July reappearance in Pittsburgh, I pulled out some interviews I did years ago with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, and Dan Fitzpatrick got many new ones of great National Leaguers of the past and their recollections of the Pirates and Pittsburgh. Many remember the eccentricities of old Forbes Field.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”7″ display=”basic_thumbnail” thumbnail_crop=”0″]

Some recall some of the greatest exploits in baseball history that happened here. Some recall friendships they gained through the game. Together, the ballplayers give a fascinating portrayal of different eras in baseball and Pittsburgh. — Douglas Heuck

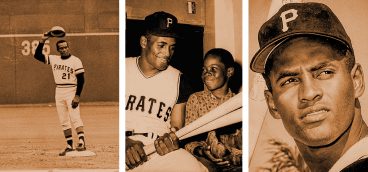

Hall of Fame third baseman Brooks Robinson, “The Human Vacuum Cleaner,” was the greatest defensive third baseman of all time, winner of 16 consecutive Gold Gloves for the Baltimore Orioles. Ask Robinson about Pittsburgh, though, and what he remembers is an error. It happened in the 1971 World Series against the Pirates, at the new Three Rivers Stadium, during the first night game in World Series history. A Pirate batter hit a sacrifice fly to the outfield, and a speedy Roberto Clemente dashed from second to third. The outfielder tried to throw Clemente out at third, and the ball “went through my legs,” Robinson said. The rare fielding mistake still annoys the 69-year-old Robinson, 35 years later. “It made me mad!”

The Orioles lost that series to the Pirates, four games to three. The year before, Robinson was World Series MVP against the Cincinnati Reds, nabbing so many hot grounders at third that Reds manager Sparky Anderson quipped, “I’m beginning to see Brooks in my sleep.”

In 1971, though, it was Clemente’s turn as World Series MVP, and Robinson still remembers how Clemente used the contest as a “showcase” for his skills —”making a catch in deep right and wheeling and throwing to third,” as just one example. “I think he always felt a little slighted, never talked about in the same breath as Mays and Mantle.” Earning MVP in a World Series, Robinson said, “was redeeming” for Clemente, who died a year later in a plane crash.

“I broke in in Pittsburgh,” said Ron Santo, a nine-time Chicago Cubs all-star. “I was 20, and I’d had one year of minor-league ball when the Cubs called me up on June 26 of 1960. Growing up in Seattle, I’d never been in a major league park in my life, and now I was going to Forbes Field. When I walked into the park, I just sat down in a box seat and watched the Pirates players. I used to read about these guys: Clemente, Mazeroski, Don Hoak, Bill Virdon. I was in awe.”

“Manager Lou Boudreau had penciled me into the lineup. I was so nervous for batting practice that I didn’t hit a ball out of the cage. I didn’t go in the clubhouse after batting practice like the others. I wanted to sit on the bench and listen for my name to be announced. And this was a doubleheader, with Pirate Bob Friend starting the first game and Vernon Law the second. That was the year the Pirates won the Series. Law won 20 games and Friend won 18. Ernie Banks was sitting next to me, and he said, ‘Don’t worry about who’s pitching. Think of them as AAA pitchers.’ I said, ‘That’s easy for you to say.’

“We went down one-two-three in the first. When I walked to the plate in the second, there were 40,000 people in the stands. I thought they were all watching me and knew it was my first day. Smoky Burgess was catching, and my knees started to shake. My hands too. I stepped out to relax. I stepped back in and Smoky said, ‘Are you nervous, kid?’ I jumped back and said ‘No.’ I was startled that he said that. He must have been watching me shake.

“Friend threw a curve. I bailed out, and it broke for inside strike. And as Smoky threw the ball back to Friend, he went right to my ear and he said, ‘That’s a major-league curveball, kid.’ The next pitch was a fast ball, and I hit a line drive up the middle for a base hit. When I got to first base, the weight of the world left my shoulders. I went 4-7 with 5 RBIs, and we won a doubleheader against the Pirates. And that’s always been one of my favorite parks, and Pittsburgh’s always been one of my favorite cities.”

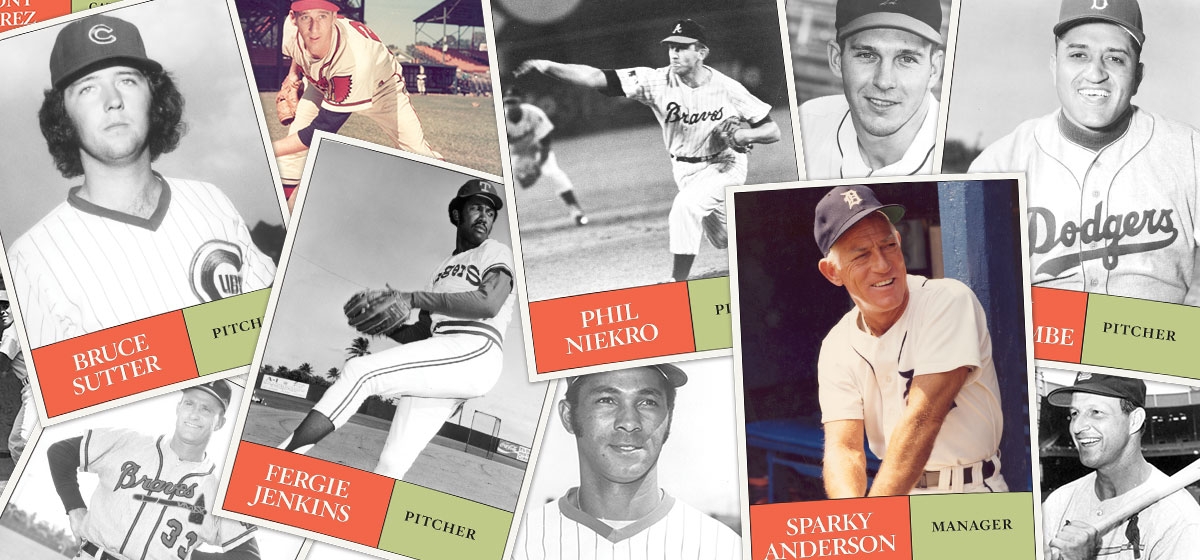

Hall of Fame right-handed pitcher Ferguson “Fergie” Jenkins, a Cy Young award-winner for the Chicago Cubs, liked Forbes Field because it was a big, pitcher-friendly ballpark, but the ground-ball specialist struggled on the faster turf of Three Rivers Stadium, where he had a losing record against the “Lumber Company” teams of Willie Stargell, Al Oliver and Roberto Clemente. Regardless of Jenkins’ performance, the Canadian always returned to Pittsburgh in the late fall and winter for deer hunting, bass and trout fishing. His companions and hosts were Pirates players Stargell, Doc Ellis, Bill Mazeroksi and Bob Veal. He and Veal, who lived inAlabama, would meet in Pittsburgh immediately after Thanksgiving and hunt for white-tail deer near Ford City and Kittanning. Jenkins’ most memorable moments?

“I caught a nice rainbow trout in ’68, ’69,” Jenkins said. “A little over five pounds. I was fly fishing up near Kittanning with Bob Veal at the time.” In the winter of 1968, “I shot a nice 10-point buck in Kittanning. Two hundred and twenty pounds.” Jenkins, now 63 and living in Arizona, will be back in Pittsburgh this July, for the All-Star game. He hopes to reconnect with friends and “recall all the memories.” And maybe do a little fishing, too.

In 1949, Brooklyn pitcher Don Newcombe became the fourth black player in the majors. He remains the only major-leaguer to win Rookie of the Year, the Cy Young Award and Most Valuable Player Award. “I’ll always remember Forbes Field and the clubhouse man. He was in the visitors’ clubhouse then. He sure was a nice guy. They’d have everything set up for you, and they’d take care of you. They’d have your uniform hung up. They’d have your shoes shined. I used to tip them.

“I remember Bob Prince. He was named appropriately. And Rosie Rowswell. They and the others in Pittsburgh were nice when you didn’t have to be nice to black ballplayers. And Branch Rickey was in Pittsburgh in 1950. He was the man who gave me my chance, along with Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella, to be what we became. He gave us a chance to have a life for ourselves and our families.

“We had some friends there. Mal Goode with the Pittsburgh Courier, and Bill Nunn, president of the Pittsburgh Courier. Mal spent so much time making it right for us and making us comfortable. We needed to get out of the hotel room, he’d say. And he’d take us down to the Loendi Club on the Hill. And Gus Greenlee had a club just around the corner.”

Before the Dodgers, Newcombe had played against the Homestead Grays in Pittsburgh when he was with the Newark Eagles in the Negro League. “We couldn’t stay at the same hotels as we did later with the Dodgers, but the owner couldn’t afford it anyhow, even if we could’ve stayed there. We stayed at the black hotels on the Hill. The Hill was very vibrant. I remember the beautiful women and the wonderful people who helped make it nice for us because of what we were doing.

“You didn’t ever hear people yelling racial epithets at you in the park in Pittsburgh. The people and the ball team were pretty damned nice to us. In the early years, when we really needed somebody to help give us a chance to play ball on our merits and not our skin color, the Pittsburgh fans were at the top of the list, in my opinion. Maybe that might mean something to your readers, because it still means something to me.”

During Billy Williams’ 18-year career, the six-time all-star won a batting title with the Cubs, was Most Valuable Player Runner-up twice behind Johnny Bench and won induction into the Hall of Fame. When he thinks of Pittsburgh, he thinks of music. “Forbes Field had a great sound system and they played the music of the 60s,” said Williams, who came to the majors in 1959. “After the ball game, we spent a lot of time over at the Crawford Grill in the Hill. I was into jazz, being from Chicago, and the Crawford Grill had a lot of name musicians. Plus, my wife’s uncle — they called him Curly — was the cook and he made sure I got a good meal.”

Warren Spahn, the most victorious left-handed pitcher in history, first arrived at Forbes Field with the Boston Braves in 1946, fresh out of the Army. “I remember, emphatically, the clubhouse guy put a nail in the wall and that was my locker. They didn’t have any room. Theclubhouse floor was wooden blocks. It was like tile, but I think it was dirt between the blocks.” Pitching there wasn’t easy, said Spahn, who won 363 games in 21 years. “Home plate was so far away from the stands that it made it feel that you were pitching in a plowed field. As in golf, where it’s hard to judge a distance when there’s no trees behind the green, the same is true in pitching. I remember the Cathedral of Learning was prominent over the fence. And the longest homer I ever saw was there. Jeff Heath hit it into center field, where they used to keep the batting cage.” Spahn, a Hall of Famer, died in 2003.

Hall of Famer Stan “The Man” Musial grew up in Donora and went on to become one of the greatest hitters in baseball history. His career numbers: 475 home runs, 3,630 hits and a .331 lifetime batting average. “I went to my first game at Forbes Field when I was 16. A sportswriter took me. I rooted for Paul Waner then. You couldn’t see a game on television then.” When he returned to Pittsburgh in 1941 as a St. Louis Cardinal, he hit his first bigleague homer. “My family and friends were there. It was a big park, with a very hard infield. Left field and center were really big, and it was hard to hit one out. Down to right was a little shorter. My first home run went there.”

Musial played in 24 all-star games, a record held by himself, Willie Mays and Hank Aaron. “I enjoyed playing in Pittsburgh. They had great fans. They didn’t have such good teams in those days, the ’40s and ’50s.

“A guy named McManus had a restaurant where the sports guys hung out. I used to hang around with Billy Conn, Fritzie Zivic and Art Rooney. Art was a great friend. He loved baseball and was always at the games. We used to go to the Pittsburgh Athletic Association (PAA) for dinner. And I loved the fight game. I loved Billy Conn. He was a quiet guy, and he loved baseball. We’d get together a lot. Fritzie was a boxing champion. There must have been four or five of them in the family. All fighters. Rough and tough, you know. Never a dull moment.” He remembered Pittsburgh as “smoky and dusty and dirty. Donora was the same way, with the mills and the smokestacks always going.”

Known as “The Toy Cannon,” short slugger Jimmy Wynn with Houston’s Colt 45s and Astros got his first major league start here in 1963. “I remember I was playing shortstop in that game and I almost got killed by a line drive by Clemente,” said the three-time all-star. “We had the infield in, and Clemente hit one that ricocheted off my glove, off the top of my hat and went into center field for a triple. My thought was, ‘Get the married men off the infield, quick!’ Pittsburgh was, to me, a very casual, warm city. Clemente and I talked about hitting and how to hustle. My best friend in Pittsburgh, though, was Willie Stargell. We talked a great deal about baseball and how to react to the fans.”

Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson recalled the 1970s, when he was at the helm of Cincinnati’s Big Red Machine and the Pirates were his arch rivals. The venue for those memorable battles was Three Rivers Stadium. “I always enjoyed Pittsburgh, and especially the fans. They were working people. My father was a house painter and so were my grandfather and my uncle. That’s the way I was raised. That’s the way I still am. Pittsburgh being a working town, when those people spent their money to go to a ball game, they had to dig down deep to bring their children. That’s a special occasion. To me, that’s priceless.

“We called the Pirates the Lumber Company. You knew that it would be very easy for them to unleash on you. There was a game in Cincinnati and they beat us 19-2. They had 20-some hits. Two bloops and the rest were bullets. And Manny Sanguillen hit four line drives in a row for outs. The Pirates were great. People don’t understand today, the teams you used to see. We don’t see teams today like those teams. We see good teams—don’t get me wrong. But not those type of players all on one club. If they caught a pitcher that wasn’t right, they’d crucify him. Believe me. I’ve seen Stargell hit balls. Oh, my God. But they had it right on through their lineup: Oliver, Clemente, Stargell, Hebner, Alley, Alou, Mazeroski, Sanguillen.

“The best player I personally ever saw — and I never saw Mays in his prime, so I can’t argue that — but the best I have ever seen to this day is Roberto Clemente. Bobby was unreal. He was better the last couple years before he got killed than he was in his younger days. He had the body of a kid in his mid-20s. People didn’t realize how fast he was. He only stole bases if it meant something. In the outfield, nobody could play that position like him.”

Richie Ashburn, the six-time Phillie all-star, two-time batting champ and Hall of Famer, recalled the Schenley Hotel in Oakland above all else. “It was a great place to spend a few days,” said Ashburn, who played from 1948 to 1962, and died in 1997. “Big, kind of homey. It had a big porch on it, and that’s where we’d have breakfast. When the weather was good, we’d just sit out there on rocking chairs. It wasn’t one of the big hotels you see now, where it’s so commercial. We knew all the people who worked there—the bellboys, the waiters and waitresses. Baseball wasn’t nearly as much of a business then. We just kind of enjoyed what we were doing, and at the hotel, it felt like a summer resort.” The University of Pittsburgh acquired the hotel in 1956 and it now houses the student union.

Lew Burdette, the three-time Milwaukee Braves all-star, is best known as the winning pitcher in the fabled game in which Pirate Harvey Haddix pitched 12 perfect innings before losing in the 13th. “It was going along real fast,” recalled Burdette. “I didn’t take a lot of time between pitches, and Harvey was just a machine that night. I made the last out in the 3rd, 6th 9th and 12th innings. In the bottom of the ninth, I was agitating Smoky Burgess, telling him I was going to break up the no-hitter. ‘It’s getting ridiculous. I’m going to hit one out.’ Then in the 12th, I told him it was getting really ridiculous. He laughed.” Teammate Joe Adcock ended the famous duel with a home run in the 13th. “It was an exciting game. But I really felt sorry for Harvey, losing that game. You know that won’t be done again. Hell, no. Not nowadays. They don’t get to pitch six innings.”

Hall of Fame relief pitcher Bruce Sutter, who befuddled hitters with a split-finger fastball, got his first save in Three Rivers Stadium on May 23, 1976. The Chicago Cubs rookie got the ball in the ninth inning. His parents from Mount Joy, Pa., were watching him play major-league ball for the first time. Pirates hitters Bob Robinson, Richie Zisk and Richie Hebner all “hit balls right to the fence,” said Sutter, now 53. All were “fly balls caught. I gave up over 1,000 feet on three outs. I thought they were homers. But the park held them. I was thrilled to get my first save, but I didn’t exactly wow them that day.” After the game, his dad, a quiet man, “didn’t say much,” Sutter said, except: “Congratulations. Hope this is the first of many.”

Sutter, who would save 300 games, was intimidated by the Pirates’ lineup in those days. “They always had great big guys who could launch them. Big Willie (Stargell), (Dave) Parker, Olie (Al Oliver).” Sutter recalled a warning from (Cubs pitcher) Rick Reuschel in the Three Rivers dugout: “’Don’t watch batting practice. It will be intimidating,’” Sutter didn’t heed the advice.

“I had to see it for myself,” he said. And, “it was impressive.”

Hall of Fame pitcher Phil Niekro won 121 games after he turned 40, a feat attributed to his mastery of the knuckleball, a slow, floating pitch that deceived hitters. “Knucksie” knew Pittsburgh from an early age. He went to high school across the Ohio River from Wheeling, W.V., and Pittsburgh was always “the big city near me… like New York,” said Niekro, 67. In grade school, he made field trips to the Greater Pittsburgh International Airport, and “I didn’t think anything was bigger in the whole world.”

In high school, Niekro faced Bill Mazeroski, another schoolboy star from Tiltonsville, Ohio. Years later, when Mazeroski was the Pirates’ All-Star second baseman and Niekro an All-Star with the Atlanta Braves, they faced each other on Mazeroski’s 30th birthday. Mazeroski hit a grand-slam off Niekro, and as he rounded second base, Niekro called over “Happy Birthday — Have a nice day.'”

Niekro remembers one game in particular. “Eddie Matthews was managing the Braves. We were winning 1-0 or 2-1 and Willie Stargell came up. I got behind 2 balls and no strikes. Matthews stormed out to the mound and said “‘Throw the ball right down the middle. Who do you think he is, God? Think he’ll hit it up in the deck in center field?'”

“I think Stargell read his lips,” said Niekro, who delivered the ball as ordered, and “Eddie didn’t get back to the dugout before Stargell hit the ball exactly where we were talking about – the lower deck of Three Rivers Stadium.”

“I came back to the dugout and told Matthews, He might be Him.”

“Pittsburgh’s like a second home to me,” said former Cardinals catcher Joe Garagiola, who spent two years as a Pirate. “I loved Forbes Field, especially when they cut down the space between home plate and the stands. Before they did that, you could make it home from second on a passed ball. That was embarrassing for a catcher. Forbes Field was a beautiful park. You could look out to left and see Schenley Park. It was a legitimate home run when you hit one there. I’ll tell you how deep it was. The batting cage just sat out in center field in fair territory the whole game. At that time, it cost $3.60 by cab to get out that far.

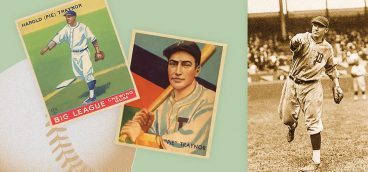

“My only Pittsburgh regret was that I didn’t record the stories of Hall of Famers Honus Wagner and Pie Traynor. I used to sit on that bench and just listen. The whole atmosphere was great in Pittsburgh. It was a delight to sit with the ushers, whether I went in as a player or broadcaster. Pete Argentine, the head usher — I used to go to his house for dinner. When I’d come back in town, one of the ushers would say, ‘So and so passed away,’ and I would feel it. It was different then. And when they were hurting, you were hurting, from players to ushers to groundskeepers. John Fogarty was head groundskeeper. They called the infield Fogarty’s Brickyard. The groundskeeper was, before artificial surface, like the 10th player on the team. If you had a sinker ball pitcher who would get a lot of ground ball outs, the first bounce was the important one. So the groundskeeper would keep the ground in front of the plate soft to deaden the bounce. If you had a fast club, you’d want it hard so the ball would go straight up and the batter could beat it out. If your club could bunt, you’d slope the dirt in between the grass and the baseline line and add an extra coat of paint on the foul line. So the ball would stay fair. If you had a slow third baseman, and the other team was going to bunt, you’d slope it the other way.

“The greatest catch I ever saw was in that park. It was a Friday night. Rocky Nelson hit a bullet to left center and it was curving away from Willie Mays. Willie turned the wrong way, but at the last minute, he stuck up his hand and caught it bare-handed.”

Hall of Fame pitcher Gaylord Perry, master of the illegally doctored “spitball,” won his first major-league game 44 years ago in Pittsburgh, the beginning of a 314-win, 3,534-strikeout career with eight different teams.

Perry, now 67 and living in Spruce Pine, N.C., remembers the old Forbes Field as a setting for several oddball incidents. The first was in 1964, during Perry’s second full year with the San Francisco Giants. Before a game against the Pirates, Perry watched batting practice with San Francisco Examiner sportswriter Harry Jupiter and Giants manager Alvin Dark, and Jupiter, regarding the 6- foot-4, 215-pound pitcher from rural North Carolina, said: “Hey Alvin, this prairie lad might hit some home runs for you.”

Dark, famously, responded with a prophetic retort: “There will be a man on the moon before Perry hits a home run,” the manager said, according to Perry. Five years later, on July 20, 1969, minutes after the Apollo 11 touched down on the moon with Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong aboard, Perry hit the first home run of his career in San Francisco.

Perry’s second bizarre Pittsburgh memory involves left-handed Pirates pitcher Billy O’Dell, a South Carolinian who played for Pittsburgh in 1966 and 1967.

Inside Forbes Field, a park that attracted lots of birds, O’Dell “used to go shoot pigeons before batting practices (with a shotgun),” Perry said. “I said, ‘Billy, aren’t you going to get in trouble?’ Billy said, ‘Pittsburgh gets so many pigeons; they want to get rid of some.'”

“They let him do that!” Perry said. “Now you get locked up.”

A third Pittsburgh memory involves the 1974 All-Star game, played in Three Rivers Stadium. Perry, the starting pitcher, struck out Cincinnati Reds greats Pete Rose, Joe Morgan and Johnny Bench—all in the same inning. But he never did figure out Pirates Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente.

“They said don’t pitch him inside. I didn’t pitch him inside for three or four years. When I did pitch him inside, he hit a home run… the wind blowing 30 miles per hour against him. He hit it 25 rows deep.”